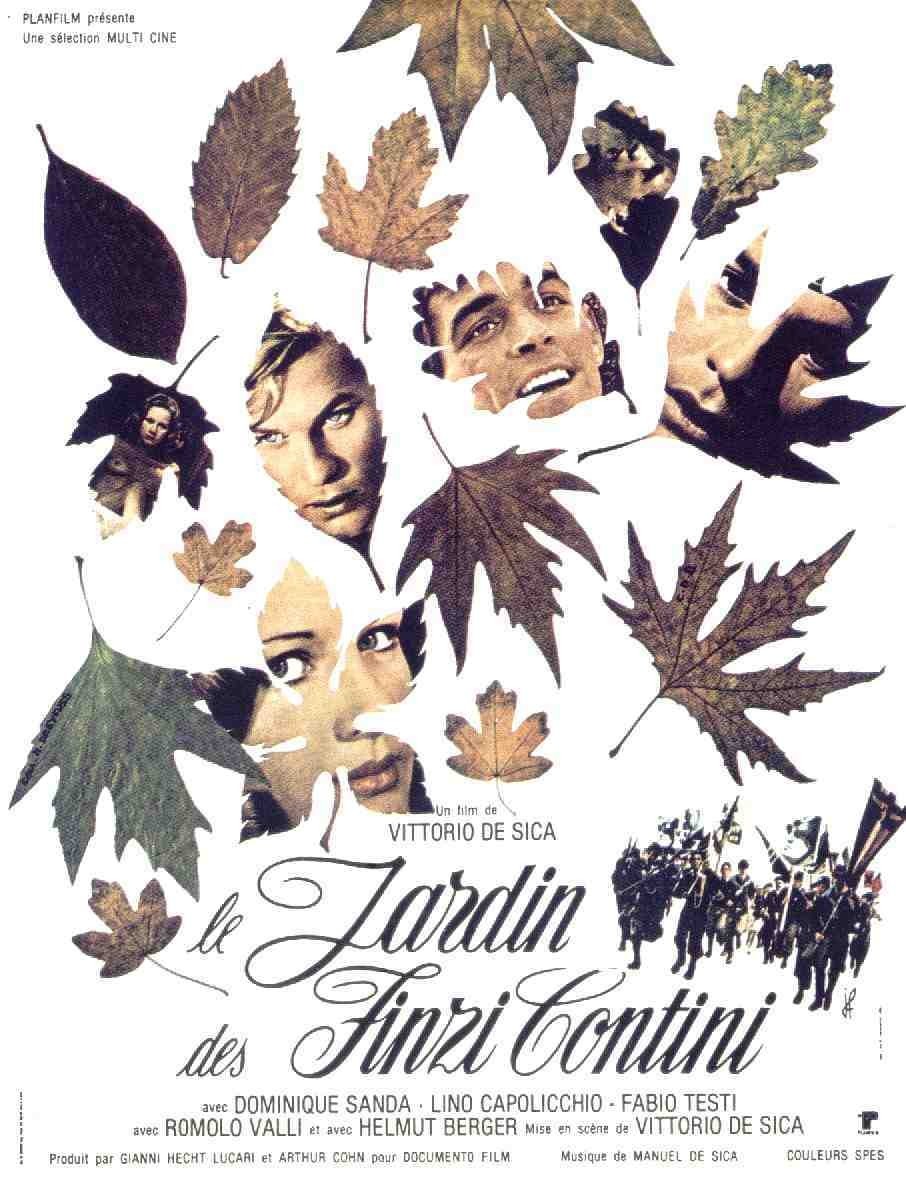

“The Garden of the Finzi-Continis,” as nearly as I can tell, is not an enclosed space but an enclosed state of mind. Eager for an afternoon of tennis, the young people ride into it on their bicycles one sunny Sunday afternoon. The Fascist government of Mussolini has declared the ordinary tennis clubs off limits for Italian Jews — but what does that matter, here behind these tall stone walls that have faithfully guarded the Finzi-Contini family for generations?

Micol, the daughter, welcomes her guests and gives some of them a little tour: That tree over there is said to be five hundred years old and might even have been planted by the Borgias. If it has stood for all those years in this garden, she seems to believe, what is there to worry about in the world outside?

She is a tall blonde girl with a musical laugh and a way of turning away from a man just as he reveals himself to her. Giorgio, who has been helplessly in love with her since they were both children, deceives himself that she loves him. But she cannot quite love anyone, although she carries on an affair with a tall, athletic young man who is about to be drafted into the army. Giorgio’s father says of the Finzi-Continis: “They’re different. They don’t even seem to be Jewish.” They’re different because wealth and privilege and generations of intellectual and social position have bred them into a family as proud as it is vulnerable. The other Jews in the town react to Mussolini’s edicts in various ways: Giorgio is enraged; his father is philosophical. But the Finzi-Continis hardly seem to know, or care, what is happening. They are above mere edicts; they chose to live behind their walls long before the Fascists said they must.

This is the situation as Vittorio De Sica sketches it for us at the outset of “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis,” which was a true surprise from a director who had seemed to lose his early genius. De Sica’s previous two or three films (especially the disastrous “A Place for Lovers“) were embarrassments from the director of “The Bicycle Thief” and “Shoeshine.”

But here he returned with a film that seems to owe little to his previous work. It is not neorealism; it is not a comic mixture of bawdiness and sophistication; it is most of all not the dreamy banality of his previous few films. In telling of the disintegration of the Jewish community in one smallish Italian town, De Sica merges his symbols with his story so that they evoke the meaning of the time.

It was a time in which many people had no idea what was really going on. Giorgio’s younger brother, sent to France to study, finds out to his horror about the German concentration camps. There has been no word of them in Italy, of course. Italy in those final prewar years is painted by De Sica as a perpetual wait for something no one admitted would come: war and the persecution of the Jews.

The walled garden of the Finzi-Continis is his symbol for this waiting period. It seems to promise that nothing will change, and even the Jews who live in the village seem to cling to the apparent strength of the Finzi-Continis as assurance of their own power to survive.

In presenting the garden to us, De Sica uses an interesting visual strategy; he never completely orients us visually, and so we don’t know its overall size and shape. Therefore, visually, we can’t count on it: We don’t know when it will give out. It’s an uneasy feeling to be inside an undefined space, especially if you may need to hide or run, and that’s exactly the feeling De Sica gets.

The ambiguity of the garden’s space is matched by an understated sexual ambiguity. Nothing happens overtly, but De Sica uses looks and body language to suggest the complex varieties of sexual attractions among his characters. When Micol is discovered by Giorgio with her sleeping lover, she does a most interesting thing. She covers him, not herself, and stares at Giorgio until he goes away.

The thing is, you can’t count on anything. And nothing permanent can be permitted to take place during this period of waiting. De Sica’s film creates a feeling of nostalgia for a lost time and place, but it isn’t the nostalgia of looking back. It’s the nostalgia of the time itself, when people still inhabiting their world could sense it slipping away, and already missed what they had not yet lost.