I have a soft spot for sports movies where an underdog comes up from behind, culminating in a moment of pure triumph. The genre can be hokey or sentimental, but there is an underlying power and inspiration in those cliches. “The Dark Horse” is a great example. Based on the true story of Maori speed-chess master Genesis Potini, and directed by James Napier Robertson, it’s a feel-good story with the potential to make you feel great. What makes it unique is the Maori background, the atmosphere of poverty and violence in the community, a people marked by the genocide perpetrated upon them. In that environment, chess becomes not only a life-saver for kids who are born into inherited hopelessness, but also a metaphor for strategies on how to get through life. Strategy combats chaos, strategy focuses people on one goal, and with strategy, winning is actually possible. That’s what “The Dark Horse” is all about.

Genesis Potini is the center of “The Dark Horse,” (his nickname in the chess world) and the film is as much a character study as anything else. Potini had a bipolar diagnosis (treated realistically in the film with not a whiff of condescension or grandstanding), and spent his life in and out of hospitals, with short jail stints for vagrancy. He was a phenom-prodigy at chess, winning competitions, and eventually helping form a chess club for underprivileged kids in his community called The Eastern Knights (the organization still exists today; Potini died in 2011). Potini’s older brother taught him how to play chess when they were kids, presenting the different chess pieces as nearly-mythological figures with special powers. Chess was a way for them to access the pride of their culture and history, the fact that they all “once were warriors.” It is a militaristic game played by two people, but what happens on the board is a group event, and that was how Potini viewed the game.

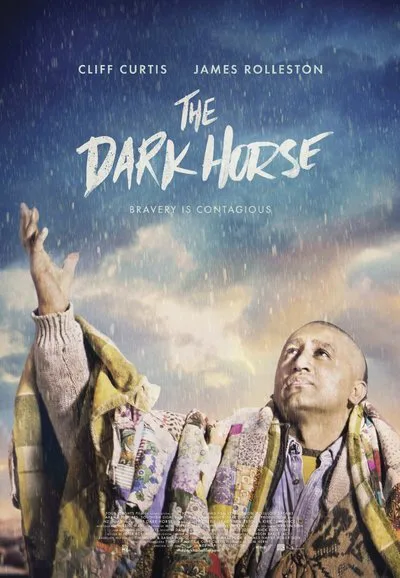

Genesis is portrayed by wonderful character actor, Cliff Curtis, so unforgettable in the Maori dramas “Once Were Warriors” and “Whale Rider,” as well as in small roles in “Three Kings,” “Training Day” and “The Insider.” (Currently, Curtis can be seen stealing AMC’s “Fear the Walking Dead.”) The actor has an imposing lumbering presence, reminiscent of Lee J. Cobb, and a malleable face. In “The Dark Horse,” he returns to New Zealand to take on one of the best roles in his career. As the toothless Genesis he is ruminative, gentle, often detached from surrounding events, but when he plays chess he is a ferocious competitor who can see six or seven moves ahead.

“The Dark Horse” opens with a dream-like sequence in which Genesis, in the grip of manic hallucinations, staggers down the middle of a street in the rain, heading into a “curios” store as though by appointment. There’s an old-fashioned chess set on display, and Genesis stands over it, dripping rainwater onto the board, playing a game against himself as the well-dressed, white customers stand back, watching. Genesis is taken off to jail for disturbing the peace, and then released into the custody of his older brother, Ariki (Wayne Hapi). Ariki is entrenched in Maori gang-culture, the house filled with scary-looking drunk tattooed guys who stare at Genesis with contempt.

Genesis seeks out an old chess buddy, who runs an after-school chess club for local kids and offers his services as a coach. It is when Genesis starts teaching the kids chess in an old ramshackle shed that the film takes off. The group of kids are not professional actors. They come from Genesis’ world. They look like street kids; trash-talking, rambunctious, but also incredibly sweet and transparent to the camera. Genesis is an excellent and inspiring teacher, and decides, on impulse, that he wants to take the kids to the Auckland junior chess tournament. To say that it’s a “long shot” that the kids will make any kind of a good showing in Auckland is an understatement.

“The Dark Horse” takes time to portray Genesis’ conflicts with his brother, his growing relationship with his nephew Mana (the young James Rolleston, in an extraordinary performance), and his devotion to passing on his love of chess to the kids, hoping that it will provide for them what it provided him: guidance, a sense of possibility, and maybe even a “way out.” This central theme is made most explicit in the case of Mana, who is in the process of going through a brutal gang-initiation, at his father’s urging.

The film is inspired by “Dark Horse,” Jim Marbrook’s 2003 documentary about Potini. Robertson spent time with the real life Potini while adapting his story into a dramatic feature. He has a great respect for the bare bones of the story, and relishes the exuberance of the kids, their different personalities, their transformation into competitors. The chess tournaments are total nail-biters. Dana Lund’s score pulses beneath much of the action, throbbing single notes that underline the urgency, rather than manipulating audience-response.

The way “The Dark Horse” unfolds may be the ultimate in sports-movie cliches. But that doesn’t mean there is no suspense, that it’s a “done deal” that the kids will be able to handle the pressure of entering a mostly white middle-class pursuit such as chess. (In this respect, the film is reminiscent of “Stand and Deliver,” another sports-genre movie, where Edward James Olmos plays an inner-city math teacher determined to teach calculus to a student population underestimated and ignored.)

As Genesis gives his chess lectures, he has a couple of rules for his students. Their main job is to protect the King. Protecting the King takes on enormous significance considering their shared history. It’s part of their epic story. Another rule he drums into them is that no piece on the board should be left behind. Circle the wagons around your community. Try to save everyone. And finally: Don’t keep the focus on the rigid lines of figures on the board’s edges, but launch yourself out into the center. The center is where the real battle goes down.

Miguel Najdorf, the Argentianian grandmaster, said of Bobby Fischer, whose ruthlessness on the chess board was legendary: “Fischer wants to enter history alone.” Genesis Potini, also ruthless when playing, viewed chess as a group endeavor (on the board and off). Entering history may not have been his goal, but if he were to enter history, his group must come with him.