The planet, we are informed, is warming. The ice caps are melting.

Climates are changing. Scientists blame factory smokestacks, car exhausts and the destruction of the rain forests. “The Arrival” has a more terrifying hypothesis to explain the phenomenon. In the great paranoid tradition of science fiction, the discovery of this possibility is made by one man who cannot get anyone to listen to him and who grows desperate as the establishment slams its doors. The man is Zane Zaminski (Charlie Sheen), a radio astronomer who listens for signs of intelligence from outer space. Unlike his colleagues, he’s looking in the noisy FM band: “It’s like searching for a needle,” his partner tells him, “in a haystack of needles.” When he picks up an unmistakable signal, Zane takes it gleefully to his boss (Ron Silver), only to be told that the government’s entire intergalactic eavesdropping operation is being scaled down because of budget cutbacks. Zane’s frustration is the engine for a science-fiction film of unusual intelligence that keeps on thinking all the way to the end, springing surprises and ideas. The movie is as smart as “Mission: Impossible” is dumb.

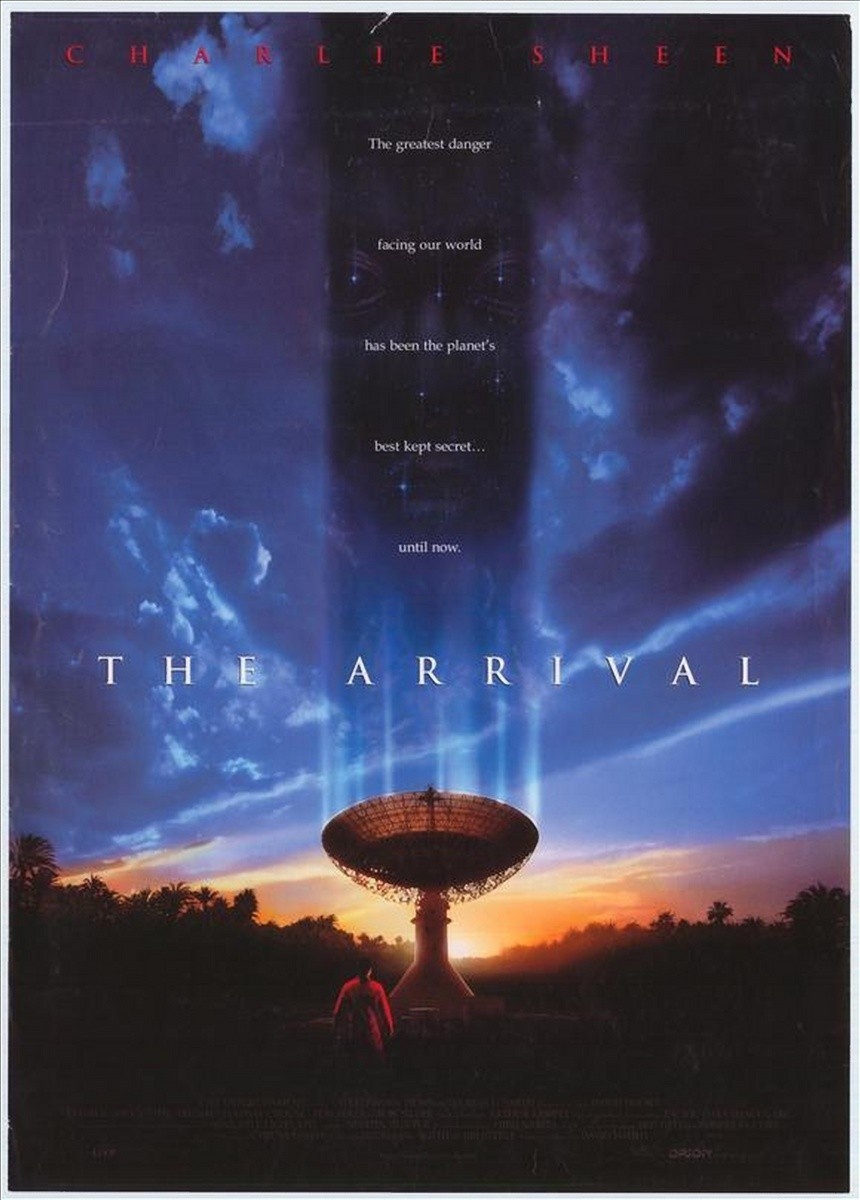

“The Arrival” is always clear about its science, its plot, its characters and its meaning, unlike “Mission: Impossible,” which is concerned with surface flash, visual impact and action. (That’s not to say “Mission: Impossible” isn’t entertaining; I am simply making the comparison.) Zane is dumped from his job but cannot shake the conviction that he did indeed hear an intelligent signal from another planet. He’s kind of a nerd with a goatee and a pocket protector, who can duplicate a science lab in his own attic with a couple of good computers and a soldering iron. Aided by a smart kid from next door (Tony T. Johnson), he soon has his own listening station up and running. His method for duplicating a big government radio telescope is ingenious: He gets a job as a repairman for consumer satellite dishes, secretly wires them into a network and puts together his own “phased array” to listen to space. I have no idea if this would work, but I like his attitude. His investigation of the signals leads him to Mexico, where he encounters another scientist, played by Lindsay Crouse. We’ve seen her in the film’s splendid opening sequence, which begins with her sniffing a flower in a meadow, and then pulls back to show the meadow surrounded by thousands of square miles of arctic ice. Together, they speculate about global warming and its possible connection to the strange situations they encounter in a small central Mexico village. At one point, frightened by where her reasoning is leading her, she sighs, “I get so damned apocalyptic when I drink.” Read no further if you plan to see the film. What I appreciated about “The Arrival” is that it stays with its thesis all the way to the end. It has a chilling hypothesis: Earth is being” terraformed” by an alien species that would prefer the planet a little warmer before it moves in. Combining this idea with a touch of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers” and some ambitious special effects, “The Arrival” springs surprises on us right to the end; the screenplay is by David Twohy (“The Fugitive”), who also directed, and who doesn’t run out of steam. Consider, for example, a clever little spinning globe that seems to work as a vacuum cleaner, sucking everything into another dimension. The job it does on a gigantic radio telescope is one of the best recent examples of special effects. There is a shot when Zane’s fiancee (Teri Polo) rolls to the edge of the big dish; at first, all we see is its vast white expanse, and then suddenly we see the earth below, spread out beneath her. The way the shot is constructed makes it into 10 seconds of just about perfect cinema. A lot of movies in this genre break down in the end into a simpleminded series of chases and fights. There are fights and chases in “The Arrival,” but they’re generated by the plot and punctuated by revelations and possibilities, so that the movie keeps on thinking and doesn’t go on automatic pilot. “The Arrival” fulfills one of the classic functions of science fiction, which is to take a current trend and extend it to a possible (and preferably alarming) future. Unlike “Species,” which assumed that alien invaders would be monsters (or, if you read the film differently, would send monsters ahead to clear the way for them), “The Arrival” gives its aliens credit for reasoning that we might almost be tempted to agree with. “We’re just finishing what you started,” one of the aliens tells Zane, referring to the smokestacks, auto exhausts, rain forests and so on. “What would have taken you 100 years will only take us 10.” He, or it, has a point.