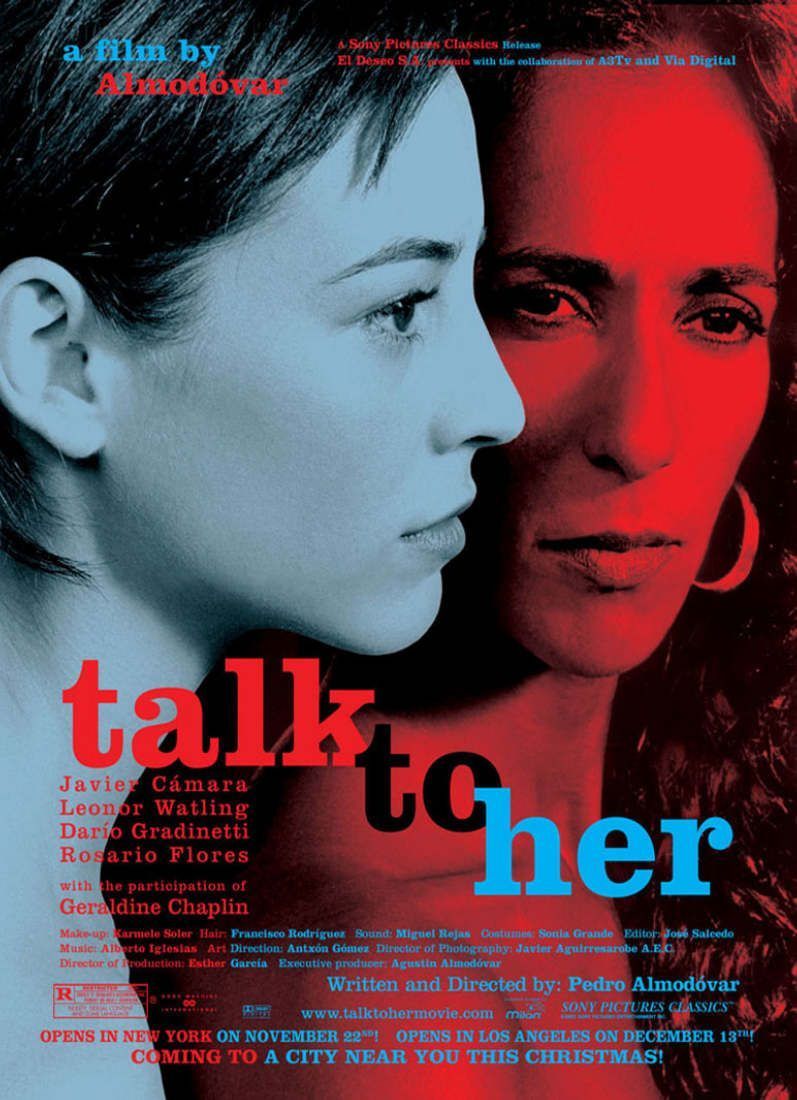

A man cries in the opening scene of Pedro Almodovar’s “Talk to Her,” but although unspeakably sad things are to happen later in the movie, these tears are shed during a theater performance. Onstage, a woman wanders as if blind or dazed, and a man scurries to move obstacles out of her way–chairs, tables. Sometimes she blunders into the wall.

In the audience, we see two men who are still, at this point, strangers to each other. Marco (Dario Grandinetti) is a travel writer. Benigno (Javier Camara) is a male nurse. The tears are of empathy, and it hardly matters which man cries, because in the film, both will devote themselves to caring for helpless women. What’s important are the tears. If he had been the director of “The Searchers” instead of John Ford, Almodovar has told the writer Lorenza Munoz, John Wayne would have cried.

“Talk to Her” is a film with many themes; it ranges in tone from a soap opera to a tragedy. One theme is that men can possess attributes usually described as feminine. They can devote their lives to a patient in a coma, they can live their emotional lives through someone else, they can gain deep satisfaction from bathing, tending, cleaning up, taking care. The bond that eventually unites the two men in “Talk to Her” is that they share these abilities. For much of the movie, what they have in common is that they wait by the bedsides of women who have suffered brain damage and are never expected to recover.

Marco meets Lydia (Rosario Flores) when she is at the height of her fame, the most famous female matador in Spain. Driving her home one night, he learns her secret: She is fearless about bulls, but paralyzingly frightened of snakes. After Marco catches a snake in her kitchen (we are reminded of Annie Hall’s spider), she announces she will never be able to go back into that house again. Soon after, she is gored by a bull, and lingers in the twilight of a coma. Marco, who did not know her very well, paradoxically comes to know her better as he attends at her bedside.

Benigno has long been a nurse, and for years tended his dying mother. He first saw the ballerina Alicia (Leonor Watling) as she rehearsed in a studio across from his apartment. She is comatose after a traffic accident. He volunteers to take extra shifts and seems willing to spend 24 hours a day at her bedside. He is in love with her.

As the two men meet at the hospital and share their experiences, I was reminded of Julien and Cecelia, the characters in Francois Truffaut’s film “The Green Room” (1978), based on the Henry James story “The Altar of the Dead.” Julian builds a shrine to all of his loved ones who have died, fills it with photographs and possessions, and spends all of his time there with “my dead.” When he falls in love with Cecelia, he offers her his most precious gift: He shares his dead with her. She gradually comes to understand that for him, they are more alive than she is.

That seems to be the case with Benigno, whose woman becomes most real to him now that she is helpless and his life is devoted to caring for her. Marco’s motivation is more complex, but both men seem happy to devote their lives to women who do not, and may never, know of their devotion. There is something selfless in their dedication, but something selfish, too, because what they are doing is for their own benefit; the patients would be equally unaware of treatment whether it was kind or careless. Almodovar treads a very delicate path here. He accepts the obsessions of the two men, and respects them, but as a director whose films have always revealed a familiarity with the stranger possibilities of human sexual expression, he hints, too, that there is something a little creepy about their devotion. The startling outcome of one of the cases, which I will not reveal, sets an almost insoluble moral dilemma for us. Conventional morality requires us to disapprove of actions that in fact may have been inspired by love and hope.

By Almodovar’s standards, this is an almost conventional film; certainly it doesn’t involve itself in the sexual revolving doors of many of his movies. But there is a special effects sequence of outrageous audacity, a short silent film fantasy in which a little man attempts to please a woman with what can only be described as total commitment. Almodovar has a way of evoking sincere responses from material which, if it were revolved only slightly, would present a face of sheer irony. “Talk to Her” combines improbable melodrama (gored bullfighters, comatose ballerinas) with subtly kinky bedside vigils and sensational denouements, and yet at the end, we are undeniably touched. No director since Fassbinder has been able to evoke such complex emotions with such problematic material.