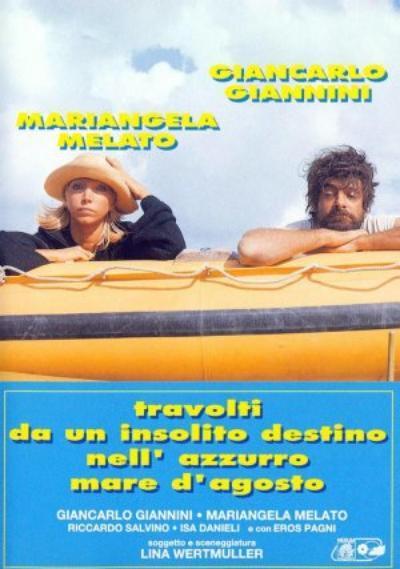

Lina Wertmuller‘s “Swept Away by an Unusual Destiny in the Blue Sea of August” resists the director’s most determined attempts to make it a fable about the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, and persists in being about a man and a woman. On that level, it’s a great success, even while it’s causing all sorts of mischief otherwise. We could have deep arguments about the meaning of it all, and no doubt we will, but as a sort of kinky update of “Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison,” the movie works just fine.

It involves a bearded sailor, who’s a fervent subscriber to the macho school of Italian thought, and a beautiful young blond, who’s the plaything of her rich husband. They’re thrown together during a luxurious yacht cruise in the Mediterranean, and the woman takes every opportunity to mock the sailor: He’s stupid, he can’t get anything right, he smells, he’s probably – worst of all – a Communist!

Late one day, the woman decides to go out in a dinghy and orders the sailor to operate the boat. He protests that it’s dangerous to leave so late in the day, but she insists. The engine fails, they’re cast adrift for days and when the sailor succeeds after great effort in catching a fish, she throws it overboard because it smells.

Eventually they land on a deserted island, and the tables in their relationship begin to turn with a vengeance. Consider. Ashore and on board the yacht, the woman held the unquestioned upper hand because of her husband’s money. But on the island, it’s the man, with his survival skills and (most controversial, this) his very masculinity, who’s the dominant figure. He orders her around. If she wants to eat, she’ll have to do his laundry. She screams, she sulks, she argues, but she loses. And she finds herself powerfully attracted to the situation; she’s been spoiled so long, it’s almost a relief to be ordered around.

It’s here that the movie begins to venture into philosophical and sexual mischief-making, because although Lina Wertmuller is a leftist, she is not, apparently, a feminist. She seems to be trying to tell us two things through the episodes on the island: (1) that once the corrupt facade of capitalism is stripped away, it’s the worker, with the sweat of his back, who deserves to reap the benefit of his own labor, and (2) that woman is an essentially masochistic and submissive creature who likes nothing better than being swept off her feet by a strong and lustful male. This is a notion the feminists have spent the last 10 years trying to erase from our collective fantasies, and it must be unsettling, to say the least, to find the foremost woman director making a whole movie out of it. And Wertmuller doesn’t kid around: Her shipwrecked couple gradually works its way into a sadomasochistic relationship that makes “The Night Porter” look positively restrained. The more the woman submits, the more ecstasy she finds – until finally she’s offending the hapless Sicilian by suggesting practices he can’t even pronounce.

Eventually, however, the man and woman have to decide between their island and a return to civilization. And the sailor can’t bring himself to believe the woman really loves him: She must prove it, he insists, by returning to shore and still staying with him. Well, not to reveal too much, Wertmuller uses the film’s ending to demonstrate that the class system still subverts our real human inclinations. None of this feels quite right; the ending is unsatisfactory in the way it follows Wertmuller’s political convictions rather than the impulses of her characters. But then I think we’re wary, these days, of movies that try to go beyond their particular stories in order to make large statements. When a movie does have a lot to say – as, for example, “Nashville” did – it’s a relief when the director finds a way to say it through the characters, instead of to them.

Still, “Swept Away” is an absorbing movie, it tells a story we get involved in and (despite all I’ve said) it’s often very funny. Giancarlo Giannini, he of the expressive eyes and slow, interior rages, is wonderful in the way he slowly reveals himself to this woman he has despised. And Mariangela Melato, as the woman, does her 180-degree personality change almost as if she doesn’t realize what’s happening. If the opening scenes in the yacht had been abbreviated and if the movie had been left open-ended – if, in short, Wertmuller had put the story ahead of her politics – I would have admired “Swept Away” more. But it’s a pleasure all the same.