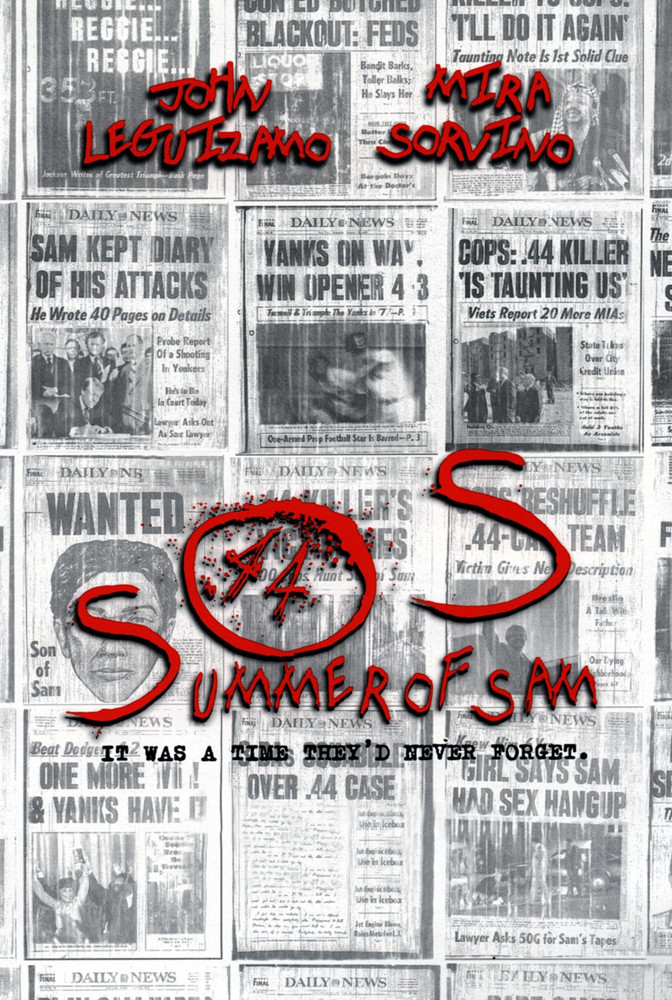

Spike Lee’s “Summer of Sam” is his first film with no major African-American characters, but it has a theme familiar to blacks and other minorities: scapegoating. In the summer of 1977, when New York City is gripped by paranoid fear of the serial killer who called himself the Son of Sam, the residents of an Italian-American neighborhood in the Bronx are looking for a suspect. Anyone who stands out from the crowd is a candidate.

Lee’s best films thrum with a wound-up energy, and “Summer of Sam” vibrates with fear, guilt and lust. It’s not about the killer, but about his victims–not those he murdered, but those whose overheated imaginations bloomed into a lynch mob mentality. There is a sequence near the end of the film that shows a side of human nature as ugly as it is familiar: the fever to find someone to blame and the need to blame someone who is different.

We see the Son of Sam from time to time in the film, often as a shadowy presence, but his appearances are more like punctuation than drama. The story centers on several characters in a tightly knit neighborhood–one of those neighborhoods so insular that everyone suspects that the killer may be someone they know. That’s not because they think a killer must live among them, but because it’s hard to imagine anyone living anywhere else.

The key characters are two couples. Vinny (John Leguizamo) is a hairdresser with a roving eye, married none too faithfully to Dionna (Mira Sorvino), who is a waitress in her father’s restaurant. Ritchie (Adrien Brody) is a local kid who has mysteriously developed a punk haircut and a British accent. He dates the sexy Ruby (Jennifer Esposito), but leads a double life as a dancer in a gay club. The movie doesn’t involve them in plot mechanics so much as follow them for human atmosphere; we get to know them and their friends and neighbors, and then watch them change as the pall of murder settles over the city.

Lee is a city kid himself, from Brooklyn, and makes the city’s background noise into a sort of parallel soundtrack. There’s the voice of Phil Rizzuto doing play by play as Reggie Jackson slams the Yankees into the World Series. The hit songs of the summer, disco and otherwise. The almost sexual quality of gossip; people are turned on by spreading rumors and feed off one another’s excitement. The tone is set by the opening shot of columnist Jimmy Breslin, introducing the film. It was to Breslin that the killer wrote the first of his famous notes to the papers, identifying himself as the monster, and saying he would kill again.

The “Summer of Sam” screenplay, written by Lee with Victor Colicchio and Michael Imperioli, isn’t the inside, autobiographical job of a Martin Scorsese film, but more of an analytical outsider’s view. We learn things. There is a certain conviction in a scene where the police turn to a local Mafia boss (Ben Gazzara) for help from his troops in finding the killer; he has power in the neighborhood, which is known to everyone, and the cops put it to pragmatic use.

We watch Vinny, the Leguizamo character, as he cheats on his wife, notably with Gloria (Bebe Neuwirth), the sexpot at the beauty salon where he works. We watch as he stumbles on two of Sam’s victims, and returns home, chastened, believing God spared him and vowing to start treating his wife better. In this neighborhood, it’s personal; if you have a near brush with Sam, it’s a sign. And Lee shows us Dionna wearing a blond wig on a date with her husband, because the killer seems to single out brunets. She does it for safety’s sake, but there’s a sexual undercurrent: Wearing the wig and risking the wrath of Sam is kind of a turn-on.

The summer of 1977 was the height of the so-called sexual revolution; Plato’s Retreat was famous and AIDS unheard of, and both of the principal couples are caught up in the fever. Vinny and Dionna experiment at a sex club, and Ritchie gets involved in gay porno films. In a confused way he believes his career as a sex worker is connected to his (mostly imaginary) career as a punk rock star. For him, all forms of show business feel more or less the same.

In the neighborhood, people hang around, talking, speculating, killing time, often where the street dead-ends into the water. One of the regulars has a theory that Son of Sam is in fact Reggie Jackson (the killer uses a .44 handgun; Jackson’s number is 44). The local priest is also a suspect; after all, he lives alone and can come and go as he wants. And then, slowly, frighteningly, attention becomes focused on Ritchie, the neighborhood kid who has chosen to flaunt his weird lifestyle.

Lee has a wealth of material here, and the film tumbles through it with exuberance. He likes the energy, the street-level culture, the music, the way that when conversation fails, sex can take over the burden of entertainment. And there is a deeper theme, too: the theme of how scapegoats are chosen. What’s interesting is not that misfits are singled out as suspects; it’s that the ringleaders require validation for their suspicions. At the end of the film, everyone’s looking for Vinny. They need him to agree with their choice of victim–to validate their fever. It’s as if they know they’re wrong, but if Vinny says they’re right, then they can’t be blamed.

“Summer of Sam” is like a companion piece to Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” (1989). In a different neighborhood, in a different summer, the same process takes place: The neighborhood feels threatened and needs to project its fear on an outsider. It is often lamented that in modern city neighborhoods, people don’t get to know their neighbors. That may be a blessing in disguise.