One of the foundations of comedy is a character who must do what he doesn’t want to do, because of the logic of the situation. As Auden pointed out about limericks, they’re funny not because they end with a dirty word, but because they have no choice but to end with the dirty word — by that point, it’s the only word that rhymes and makes sense. Lucille Ball made a career out of finding herself in embarrassing situations and doing the next logical thing, however ridiculous.

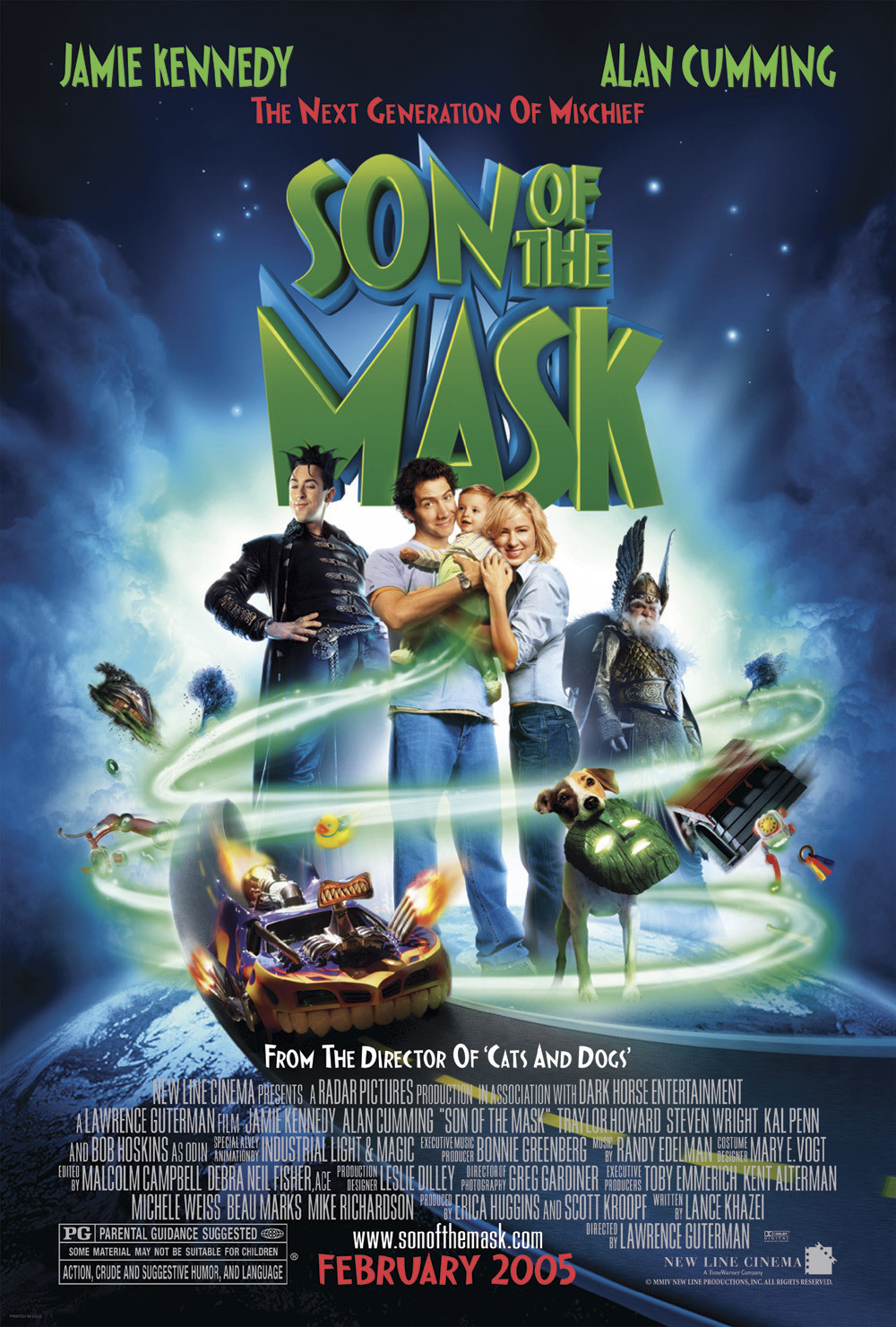

Which brings us to “Son of the Mask,” and its violations of this theory. The movie’s premise is that if you wear a magical ancient mask, it will cause you to behave in strange ways. Good enough, and in Jim Carrey’s original “The Mask” (1994), the premise worked. Carrey’s elastic face was stretched into a caricature, he gained incredible powers, he exhausted himself with manic energy. But there were rules. There was a baseline of sanity from which the mania proceeded. “Son of the Mask” lacks a baseline. It is all mania, all the time; the behavior in the movie is not inappropriate, shocking, out of character, impolite, or anything else except behavior.

Both “Mask” movies are inspired by the zany world of classic cartoons. The hero of “Son of the Mask,” Tim Avery (Jamie Kennedy), is no doubt named after Tex Avery, the legendary Warner Bros. animator, although it is “One Froggy Evening” (1955), by the equally legendary Chuck Jones, that plays a role in the film. Their films all obeyed the Laws of Cartoon Thermodynamics, as established by the distinguished theoreticians Trevor Paquette and Lt. Justin D. Baldwin. (Examples: Law III, “Any body passing through solid matter will leave a perforation conforming to its perimeter”; Law IX, “Everything falls faster than an anvil.”)

These laws, while seemingly arbitrary, are consistent in all cartoons. We know that Yosemite Sam can run off a cliff and keep going until he looks down; only then will he fall. And that the Road Runner can pass through a tunnel entrance in a rock wall, but Wile E. Coyote will smash into the wall. We instinctively understand Law VIII (“Any violent rearrangement of feline matter is impermanent”). Even cartoons know that if you don’t have rules, you’re playing tennis without a net.

The premise in “Son of the Mask” is that an ancient mask, found in the earlier movie, has gone missing again. It washes up on the banks of a little stream, and is fetched by Otis the Dog, who brings it home to the Avery household, where we find Tim and his wife Tonya (Traylor Howard). Otis snuffles around at the Mask until it attaches itself to his face, after which he is transformed into a cartoon dog and careens wildly around the yard and the sky, to his alarm. Eventually Tim puts on the Mask, and is transformed into a whiz kid at his advertising agency, able to create brilliant campaigns in a single bound.

Tim gets an instant promotion to the big account, but without the Mask he is a disappointment. And the Mask cannot be found, because Otis has dragged it away and hidden it somewhere — although not before Tim was able to wear it to bed, and engender an infant son Alvey, who is born with cartoonlike abilities and discovers them by watching the frog cartoon on TV.

A word about Baby Alvey (played by the twins Liam and Ryan Falconer). I have never much liked movie babies who do not act like babies. I think they’re scary. The first “Look Who's Talking” movie was cute, but the sequels were nasty, especially when the dog started talking. About “Baby's Day Out” (1994), in which Baby Bink set Joe Mantegna’s crotch on fire, the less said the better.

I especially do not like Baby Alvey, who behaves not according to the rules for babies, but more like a shape-shifting creature in a Japanese anime. There may be a way this could be made funny, but “Son of the Mask” doesn’t find it.

Meanwhile, powerful forces seek the Mask. The god Odin (Bob Hoskins) is furious with his son Loki (Alan Cumming) for having lost the Mask, and sends him down to Earth (or maybe these gods already live on Earth, I dunno) to get it back again. Loki, who is the God of Mischief, has a spiky punk hairstyle that seems inspired by the jester’s cap and bells, without the bells. He picks up the scent and causes no end of trouble for the Averys, although of course the dog isn’t talking.

But my description makes the movie sound more sensible than it is. What we basically have here is a license for the filmmakers to do whatever they want to do with the special effects, while the plot, like Wile E. Coyote, keeps running into the wall.

Read the complete “Laws of Cartoon Thermodynamics” here.