Although they are often charged with being emotionally distant, the British have produced more than their share of sexual outlaws, from Oscar Wilde to Aleister Crowley to D.H. Lawrence to Francis Bacon, to balance the ledger. The central figure in “Sirens” is perhaps vaguely inspired by another legendary British bohemian, Augustus John, an artist whose models and mistresses were interchangeable, and who delighted in scandal.

Named Norman Lindsay, the film’s hero is played by Sam Neill as a notorious painter who lives on an estate in Australia where his art coexists side-by-side with an experiment in living. His free-wheeling lifestyle has attracted not only a extraordinarily open-minded wife, but also a group of models for whom clothing is often optional. They share his permissive views on sensuality.

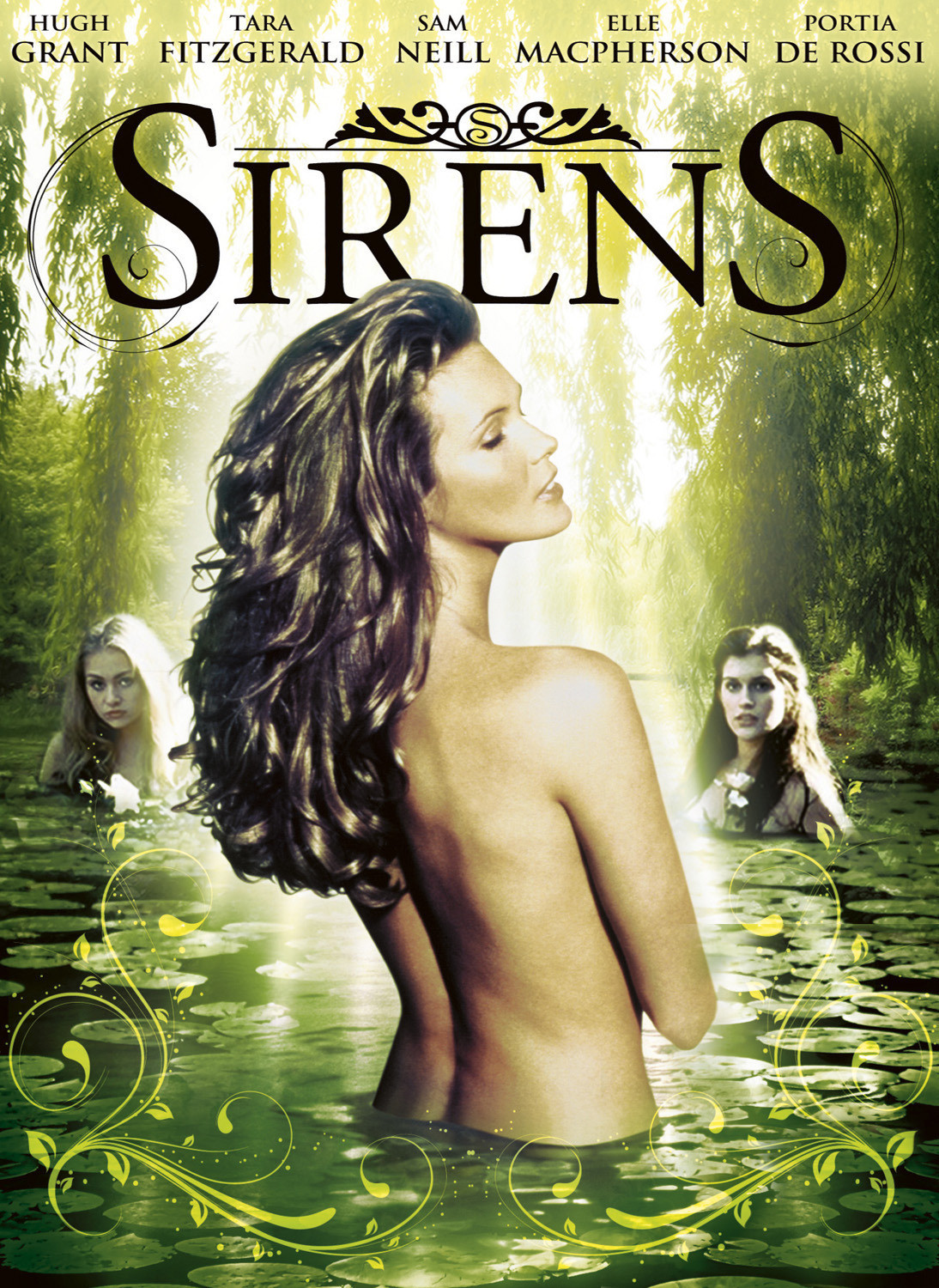

Since one of the models is played by Elle MacPherson, the Sports Illustrated centerfold, and since Ms. MacPherson is featured in the advertising above the actual stars of the movie, you might understandably have the idea that “Sirens” is an exploitation film, or at least the sort of overwrought erotic melodrama Ken Russell became known for with “Women in Love” and “Listzomania.” The movie does indeed feature much footage of MacPherson and her sister sirens in the nude, but it is smarter, more thoughtful and more good-tempered than you might expect.

The film, set between the wars, is seen mostly through the eyes of a shy Anglican clergyman named Anthony Campion (Hugh Grant), who has been asked by his bishop to look in on Lindsay during a visit to Australia. The painter is rumored to have painted a blasphemous portrait, and the bishop hopes perhaps a word to the wise will prevent a scandal. Campion and his wife Estella (Tara Fitzgerald) arrive at the painter’s sprawling estate to find a warm welcome, a guest cottage of their own,and a very gradual seduction process under way.

I can easily imagine where this premise might lead in the hands of many directors. But “Sirens” is the work of John Duigan, of “Flirting,” and he seems to be wise and relaxed about sexual matters; he sees them with both affection and amusement, and is less interested in sex itself than in his character’s shifting attitudes toward it. What we see immediately is that the bearded Lindsay is a Pan of sorts, under whose direction people are inspired to have experiences that might lessen their inhibitions. And we learn that the Campion marriage could benefit from such experiences.

The clergyman is at first quite proper and distant, and Hugh Grant is able to project his unease with great conviction. Grant (who also stars in the forthcoming “Bitter Moon” and “Four Weddings And A Funeral“) is an actor who specializes in propriety under fire. He clears his throat, he stammers becomingly, he hems and haws, he apologizes in advance for almost everything he says, and yet there is an appealing puppyish quality to his personality that inspires women to reassure him in one way or certainly another. Here he looks on with alarm as his wife grows all too intrigued by the freedoms practiced by the Lindsay menage, and yet when some of the sirens grow friendly toward him, he is hard-pressed to keep his mind on his theological duty.

There is no particular plot in “Sirens” so much as a general observation of the process by which the Campions are gradually transformed into warmer and more inquisitive partners. While that is happening, Lindsay paints, and several interlocking domestic intrigues develop without any great urgency. It’s interesting that the Lindsay character doesn’t seem to feel any need to personally direct the unfolding scenario; unlike, say, Crowley, who had a need to write the script and dominate the proceedings, Lindsay simply creates an atmosphere in which everyone feels free to act on their impulses.

The movie places little emphasis on the mechanics (or the necessity) of actual seduction, being more concerned with how the visitors absorb the philosophy of freedom which Lindsay and his sirens practice. They find a willing pupil in Estella, who becomes a particular challenge to Sheela, the MacPherson character. She invites the clergyman’s wife to go swimming at dawn, sketches her while she sleeps, and in general provides a gentle tug in the direction of more freedom.

In the hands of another director, “Sirens” might be less subtle in its style and more concerned with some kind of definite erotic payoff. Duigan would rather nudge than push. No doubt he knows all about the coteries that grew up around many infamous painters in the earlier years of this century, and is curious about how they worked, and why. By providing his British visitors as both observers and victims, he is able to study the process of seduction without making seducing the whole point of the film. The result is a good-hearted, whimsical movie which makes no apologies for the beauty of the human body and yet never feels sexually obsessed. Strange: it’s not often you smile this much during an erotic film.