“Peter and the Farm” is a very unusual and rare kind of movie: one that is good in spite of itself. Which isn’t to say that the movie’s director and co-producer Tony Stone doesn’t make some provocative, interesting choices.

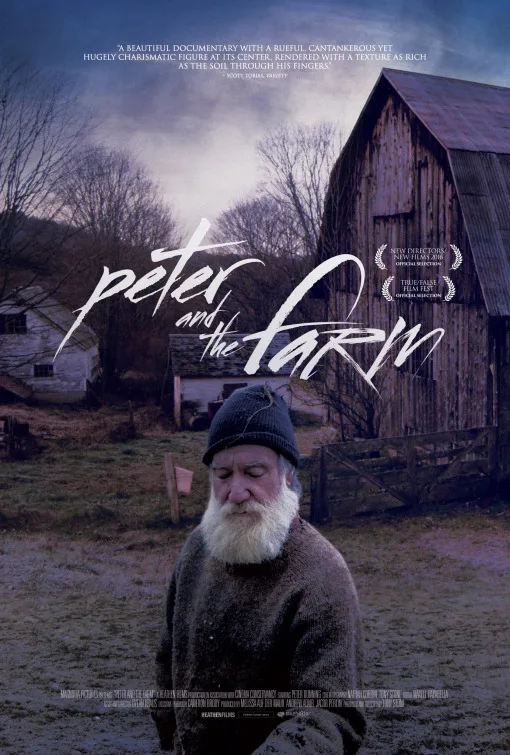

For one thing, he sets the movie, a chronicle of a year in the life of a Vermont farmer named Peter Dunning, entirely in the present tense. “Peter and the Farm” has a strangely thrilling opening shot, a car-hood’s-eye view of a winding country road in the midst of gorgeous fall foliage, rushing to a destination with decidedly non-rustic electronic music as accompaniment. Throughout the rest of the movie, Dunning, an initially vigorous looking man of nearly 70 with a gnarled left hand and a big white beard that he’s clearly earned the right to sport, will speak of his past, of the family he raised on his land, and which is no longer with him, because of his inability to get along with other people. Stone doesn’t add archival photos or footage to amplify Dunning’s tales (although later in the film we do see some family pictures on the walls of Dunning’s home). He just lets Peter tell his stories, give his point of view, something he’s eager to do in pretty much any state. The movie’s title is accurate to a fault—except for occasional glimpses of Stone and a member of two of his crew, and a cameo from a farm vet, Peter and his farm are the movie.

Dunning farms sheep, cows, pigs and some chickens, and sells their products at farmer’s markets. In the event that you were curious about how “farm to table” works, Dunning is an example, and the movie does not shy away from showing every aspect of his work. Early on, he kills and dresses a sheep, and Stone depicts the whole process, including Dunning muffing the first gunshot with which he’d intended to kill the animal. Georges Franju’s legendary short “The Blood of Beasts” took viewers inside a then-contemporary slaughterhouse half a century ago; fictional movies “Maitresse” and “1900” contained lengthy unsimulated scenes showing how your horse steak and sausage are made, respectively. What’s different here is the particular intimacy of the act. But it’s also clear that Stone wants to blow your mind with this scene, and with shots showing, for instance, the farm vet discovering that one cow is pregnant. Most adults have a sense that part of what they’re paying for when they buy meats commercially is a degree of willed ignorance about the process that brings them their food. But it does not necessarily follow that we are completely in the dark about it, and in that sense, there’s something at least mildly patronizing about the movie’s approach.

Similarly, the movie’s treatment of Dunning’s alcoholism, which he readily admits to, is a bit on the callow side. There’s a scene in which Dunning and a couple of the filmmakers drive to a bar, where Dunning proceeds to get hammered. One of the crew has to drive the pickup truck back as Dunning snoozes in a back seat. Waking up angry and disoriented, he lays into his designated driver. There’s an “isn’t this interesting” detachment to the scene that’s off-putting.

But the movie succeeds because Dunning really is, well, interesting. In spite of his disease, he maintains a spectacular work ethic, maintaining his land and his animals obsessively, driven near-mad by the sheer repetition of his tasks yet showing unyielding devotion. He has driven nearly everyone who was ever close to him out of his life, and aside from the filmmakers, who he sometimes refers to as “friends,” his only constant companion is his devoted and equally hard-working sheepdog. Dunning has accrued a lot of knowledge in a lot of different aspects of his work. Near the end of the movie he shows the filmmakers a pear tree that he planted on a hill which rises above the barn and the animals’ pens. Saying that the pears the tree first yielded were of inferior quality, he describes a branch-grafting process by which he improved the tree’s output. “It takes time,” Dunning says, the weariness in his voice suggesting that it took a great deal of time. “But it’s super cool,” one of the filmmakers says, off screen. “It takes time,” Dunning says again. There’s the movie in a nutshell.