The opening shot in “Not on Your Life” is of a bowl of stew into which bread is being broken. The camera pulls back, and we see that the stew is the luncheon of a prison guard. There is a knock at the gate, he opens it and two men come in with an empty coffin. Another knock, and a meek, rheumy-eyed little man enters. He is the executioner.

The three men go into the next room, the guard eats a spoonful of stew, and the first two men come back holding the coffin. It is occupied now. Then the little old man comes in and asks if he can have a lift to town in the hearse. Another day, another dollar.

After all, what is a man to do? No one wants to be the hangman, just as no one wants to be his victim. But juries persist in sending men to die, and there has to be someone to kill them, doesn’t there? And if they must be killed, let them be lucky enough to die in Spain, where the cruel gallows, the brutal electric chair and the messy guillotine have been replaced by the humane garrot. It breaks a man’s neck neatly, swiftly and cleanly, and he can be buried in one uncooked piece.

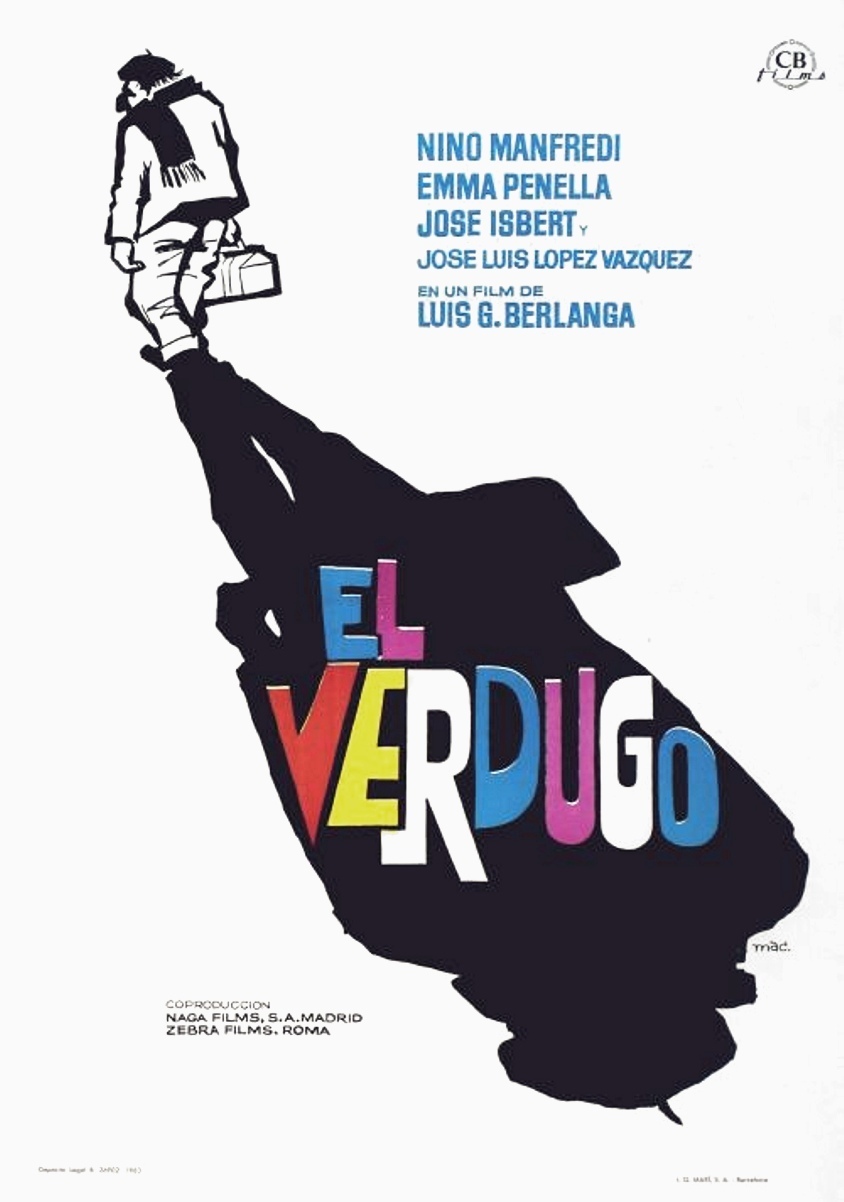

This is the simple logic of the executioner in Luis Berlanga’s macabre comedy. He has been executioner for 40 years, and in the old days the condemned men admired his skill. Alas, things are no longer as they were, and the younger generation of criminals actually resents being executed.

On the ride back to town in the hearse, the executioner (Jose Isbert) strikes up an acquaintance with the apprentice undertaker (Nino Manfredi). The executioner has a merry and buxom daughter whom no one will marry because of her father’s occupation. The junior undertaker understands; no one wants to marry him either.

The young people meet, fall in love, make love and are duly discovered in bed by the old man. “Why did you tell him I was here?” the undertaker asks furiously. “You should have gotten rid of him.” The executioner’s daughter replies sadly, “It was the safest thing to do. You forget he is capable of killing.”

The inexorable workings of convenience and economy decree that the young man will become executioner when the old man retires. But the young man is chicken. Hardly anyone starts out wanting to garrot strangers, after all, even though some people end up that way.

There is a hilarious scene in which the now-apprentice executioner and his first victim both have to be dragged to the death room and counseled by a clergyman. (“It is best that you kill him now, my son; his soul is ready for heaven. If we send to Madrid for another executioner, two or three days will elapse and he may fall from grace.”)

It all makes horrible sense, and reminds me of an exchange in Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood.” When a witness is asked the name of the hangman, he replies: “We, the people.”