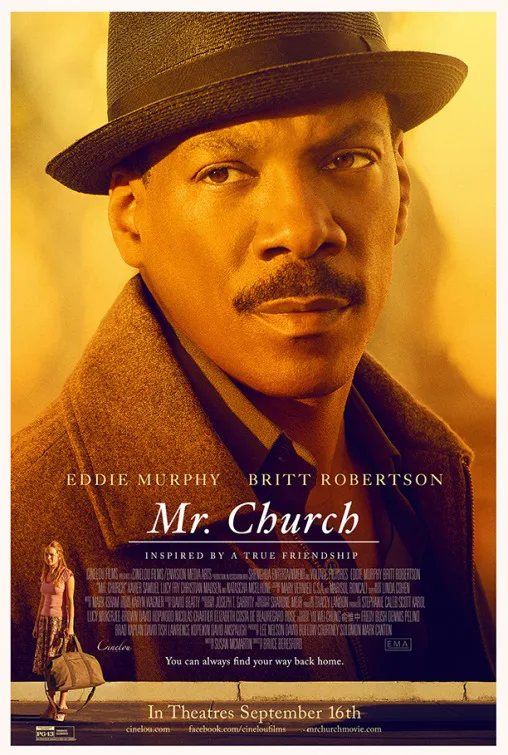

One can only speculate why Eddie Murphy would choose to end his four-year hiatus from the big screen with the extremely misguided interracial drama “Mr. Church.” If this were an attempt to secure a second Oscar nomination after his well-deserved one for “Dreamgirls,” he’s barking up the right tree. The Academy loves its servile Black people, and “Mr. Church” is directed by Bruce Beresford, who seems to be addicted to this kind of character. After helming this, an episode of “Roots” and Best Picture-winner “Driving Miss Daisy,” Beresford should be forced to join “Subservient Cinematic Negroes Anonymous” and work through their 12-step program. Until then, viewers must yet again contend with a movie where a White character gushes about what Noble Negritude has done for them.

“This is based on a true friendship,” reads the awkward title card at the beginning of the film. That friendship begins when one of the friends is sent to work for the family of the other. Marie (Natascha McElhone) is having an affair with a married man named Richard. When Richard drops dead, his will bequeaths the cooking services of Mr. Church (Murphy) to Marie and her wretched little brat of a daughter, Charlotte (Natalie Coughlin). Charlotte wants no part of Mr. Church or his food, going so far as to tell everyone in her school, “We have a new cook and HE’S BLACK!!!”, emphasizing the color for maximum shock value. Nobody gives a damn that Charlotte is throwing tantrums about Mr. Church, least of all Poppy (Madison Wolfe), Charlotte’s only friend, who is more than willing to eat his entrees.

Charlotte gives her mother a hard time about Mr. Church, not knowing that Marie is secretly dying of breast cancer. Mr. Church is tasked to be around until Marie joins Richard in the great, adulterous Beyond. Afterwards, Mr. Church will go on his merry way and Charlotte will probably go to an orphanage. Mr. Church’s stipend from Richard only covers six months of food for his charges, which coincides with the amount of time Marie has left. He is promised a lifetime salary if he does this short-term favor.

However, Marie manages to keep her cancer at bay for over six years before she gives up the ghost. This allows Charlotte to mature into a still-bratty, graduating high school senior played by Britt Robertson. Robertson narrates “Mr. Church” in long, hyperbolic passages that tell rather than show. Her words serve as the only proof of the close bond she has with Mr. Church, making their friendship ring completely hollow. Mr. Church does all the work in this relationship: He puts up with her disrespect when she’s a kid; he pays for her college education AND everything that transpires for the 5-1/2 extra years Marie stays alive; he even takes Charlotte in when she comes back from college pregnant. In return, Charlotte says nice things about Mr. Church on the soundtrack but doesn’t do squat for him on the screen until it’s too late. Watching this one-sided interaction, you almost wish Murphy had taken a page from his comedy concert “Eddie Murphy Raw” and asked Charlotte, “what have you done for me lately?!”

“Henry Joseph Church could have been anything he wanted,” Charlotte narrates in the opening scene. “He chose to cook. The secret, he said, was jazz.” We learn that Mr. Church has lots of secrets. He’s got secrets in his lemonade, in his grits and in his life. While he tells us the former two secrets, the latter one remains frustratingly unrevealed. Charlotte can’t get a single detail from Mr. Church about what he does after he leaves her house. Even after years of raising her, he won’t tell her any of his personal details, because if he does, the film cannot attempt to defend itself against the idea that Mr. Church is simply a Noble Negro with no autonomy of his own. His secrets “prove” his independence.

But Susan McMartin’s atrocious, offensive and cowardly script has no credible defense to employ. We never see Mr. Church with anyone but Charlotte, and the film is maddeningly vague about what he’s doing off-screen when he’s not with her. For example, when Charlotte moves in with Mr. Church, McMartin gives him daddy issues which manifest themselves whenever he comes in drunk after his visits to the mysterious Jelly’s Café. Beresford doesn’t even give Murphy screen time to visually enact these verbal tirades against his invisible dad; we see Charlotte listening to them in her room instead.

“Jelly’s Café had a reputation,” Charlotte tells us, which may be why Mr. Church is so afraid to mention he goes there. But what is that reputation? We never find out. I’ve got a theory that makes the movie even more offensive if I’m right (spoiler alert for the rest of this paragraph). On the surface, Jelly’s Café looks like an after-hours jazz club. It would be absurd if Mr. Church’s big, unmentionable secret is that he plays piano there, especially considering that the one personal detail he mentions in the film is that he’s a musician (plus, he plays piano for Charlotte in several scenes). I think Jelly’s Café is a gay establishment, and Mr. Church’s homosexuality is the big, scary Thing That Must Not Be Named. (At one point, Mr. Church drunkenly screams out to his dad “Don’t call me a fag!” and “Why did you put me out?!”) So not only does “Mr. Church” put a Black character in a retro role better suited for a film made in 1957, it does the same thing to a homosexual one.

Either way, this film is a stunning example of how wrong-headed filmmakers can be regarding what is acceptable for today’s audiences. Did anyone, Murphy included, stop to consider how this story of Mr. Church’s sacrifice would play to more enlightened viewers? Sure, we get the letter at the end that explains (in voiceover) what Mr. Church thinks he received from this arrangement, but wouldn’t it have been nice to have seen it play out between Murphy and Robinson, from both their perspectives instead of from just her character’s? If nothing else, Murphy is committed to the role, to the point where I wish they’d at least given him a sense of humor. That his onscreen persona has been completely neutered is the biggest sin of all in “Mr. Church.”