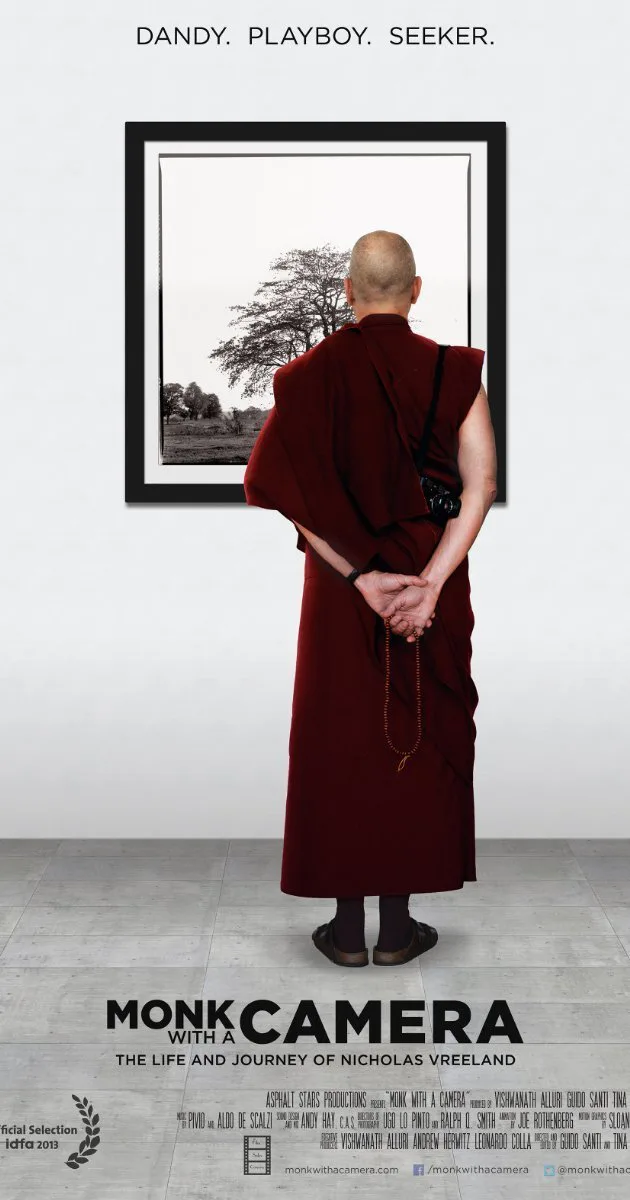

The makers of both fiction and nonfiction films often describe their narratives as journeys in which a character’s outward movements also signify an inner voyage. That’s especially true of “Monk With a Camera,” an engrossing documentary about a privileged young American who leaves fashion photography to become a Buddhist monk in India, then returns to photography to provide some crucial help to his monastery.

The film’s directors, Guido Santi and Tina Mascara, previously made “Chris and Don: A Love Story,” a moving, beautifully wrought account of the long romantic relationship between the author Christopher Isherwood and the artist Don Bachardy. Equally well-made, their latest might also be described as a love story, but here the relationship isn’t between two people but between a man and the religion he has chosen to embrace. Photography is also important to the story, but not as important as faith.

The film’s subject, Nicholas Vreeland, grew up in the most fortunate and cosmopolitan of circumstances. Born in Switzerland to globe-trotting parents, he also lived in Germany and Morocco before moving to the U.S. at age 15 and attending prep school at Groton. He knew he wanted to be a photographer from early on, and his grandmother, the legendary Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, was able to arrange for him to learn his craft under camera masters Irving Penn and Richard Avedon.

The photos we see of the young Nicky in the 1960s show an elegantly handsome young man with flowing locks, always attired in the most fashionable and impeccably turned-out clothes. He was at this point, according to his half-brother, the writer Ptolemy Tompkins, “a very committed dandy.”

Yet something was evidently missing. Rather any dramatic conversion, he and his acquaintances describe a gradual change, a slow realization that while his life was full of brilliant surfaces, he hungered for depth and meaning. These came when he began studying Tibetan Buddhism under Khyongla Rato Rinpoche, a teacher of the current Dalai Lama and founder of New York’s Tibet House.

Over time, Buddhism replaced photography as his calling. After the Dalai Lama gave his blessing to the young man becoming a monk, Nicky left his old life behind, moved to southern India and took up residence at the monastery of Rato, where his master had studied. In the film, he retraces his steps as he journeyed through the villages near Rato, and it’s clear how wondrous and strange he found the environs of his new home.

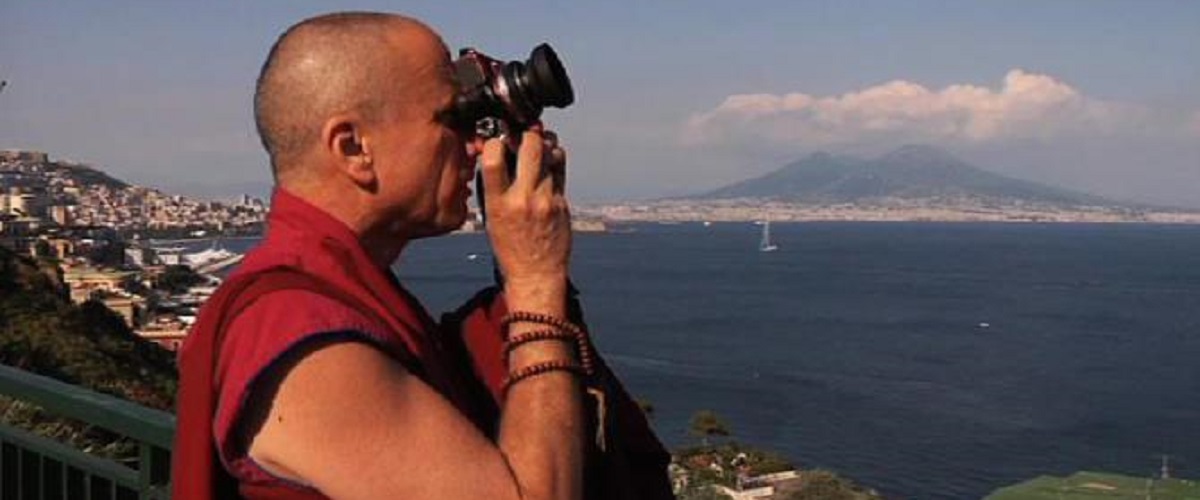

There followed years of dedicated study that included learning the Tibetan language. He only got a camera his brother had given him out of storage at the urging of the widow of Henri Cartier-Bresson, a friend. Enjoying the return to his old disciple, he recorded scenes of the monastery and its surroundings with an artist’s eye.

These became important years later, in 2008. The monastery having grown from just a few inhabitants to well over a hundred, plans were drawn up for a new compound with dormitories that could house scores of monks. But after work was begun, it became clear the financial crash meant that the project’s foreign backers wouldn’t be able to meet their pledges. What to do? In the cause of fiscal rescue, Nicky put together a selection of his best India photos and sold prints of them in major Western cities, raising $400,000 that allowed the building project to be completed as planned.

Once the beautifully appointed new monastery is up and running, the Dalai Lama announces that he wants to make Nicky its abbot. No Westerner has ever held such a position and Nicky, who seems a genuinely humble man, is not being humble when he protests that he’s not worthy of the post. But the Dalai Lama—a merry figure who seems to be laughing in every appearance in the film—has a serious aim in making the selection. Tibetan Buddhism is not a static thing, he avers. It is growing and changing, and part of that process involves its interaction with the West and believers like Nicky, whose role as abbot, he believes, will help further the cultural cross-pollination.

For the past century, pop culture representations of Tibetan Buddhism have often been simplistic, sentimental and overly idealized. “Monk With a Camera” will not do much to change that. It doesn’t begin to probe or explain the belief system that Nicky Vreeland devotes his life to, nor does it look into the darker corners of monastic life, although longtime friend Richard Gere notes the “difficulty” Nicky has had in adhering to his vow of celibacy.

Yet the contrast between aesthetics and faith that Nicky sometimes sees as a conflict in his life also provides a fascinating subtext to the film. Sometimes the beauty of the world—and images of it—can be a first step toward religious awakening and commitment. There’s a conflict between the two only when the mind allows there to be.

So, while the film doesn’t delve into the doctrines of Tibetan Buddhism, it does provide a sense of its outward life in the images of the people and rituals of the monastery to which Nicky Vreeland has devoted so much love and care. And in the portrait of the man himself, it suggests an inner odyssey as extraordinary as any journey across continents, mountain ranges and time zones.