In Prague in 1988 Russian trucks rumble through the streets and Czechs make an accommodation with their masters, or pay a price. Louka pays a price. Because in a moment of unwise wit he wrote a flippant answer on an official form, he has been bounced out of the Philharmonic and now scrapes by playing his cello at funerals, and repairing tombstones.

Life has consolations. A parade of young women visits his “tower,” an apartment at the top of a rickety old building. At 55, Louka (Zdenek Sverak) looks enough like Sean Connery to make hearts flutter, and he has the same sardonic charm. But he is broke and needs a car, and so he listens when his gravedigger pal makes an offer. The pal’s Soviet niece must get married or she’ll be sent back to Russia, where she does not want to go. The niece and her chain-smoking aunt will pay Louka to go through a phony marriage.

Against his better judgment, he does. Then the niece skips to West Germany to join a former boyfriend, leaving behind her 5-year-old son, Kolya (Andrej Chalimon). The aunt dies, and Louka is stuck with the kid. This puts a severe cramp in his love life (the kid is delivered in the middle of a would-be seduction), and besides he knows nothing about kids, and this one speaks only Russian, a language Louka has on principle refused to learn.

The outlines of this story are conventional and sentimental (is there any doubt he will come to love the child?). What makes “Kolya” special is the way it paints the details. Like the films of the Czech New Wave in the late 1960s, it has a cheerful, irreverent humor, and an eye for the absurdities of human behavior. Consider Louka’s old mother, who refuses to care for the child because she will not have a Russian in the house, and watch the scene where Russian army trucks stop outside her cottage and the kid hears his native language and runs out happily to talk to the soldiers.

Consider, too, the bureaucracy, faithful to the Soviets. Louka is subjected to a grilling by a hard-nosed official who suspects, correctly, that the marriage was a sham, but the tone of the interview is much altered because Kolya refuses to stay outside, and draws pictures all during the interrogation; his evident love for his “stepfather” is a confusing factor.

Quirky details are chosen to show the gradual coming together of Louka and Kolya. The cellist drags the kid to the funerals where he plays, and the kid watches open-eyed as the musicians play and the soloist sings. It is perhaps not surprising that his first words of Czech are the 23rd Psalm. But look at Louka’s fade when he realizes the kid is using a puppet theater to stage a cremation.

There are many women in Louka’s life, but one becomes special: Klara, played by Libuse Safrankova. He ropes her in to help him care for the child, and eventually something fairly wonderful happens, and at 55 Louka finds a way to break out of the trap of his routine. His new freedom is shown against a backdrop of the end of the Cold War, as the Berlin Wall drops, the Russians leave town, and joyous Czechs take to the streets, chanting “It’s finally over!” Louka is placed in the center of the celebrants, where he sees, of course, his former bureaucratic interrogator now part of the joyous crowd.

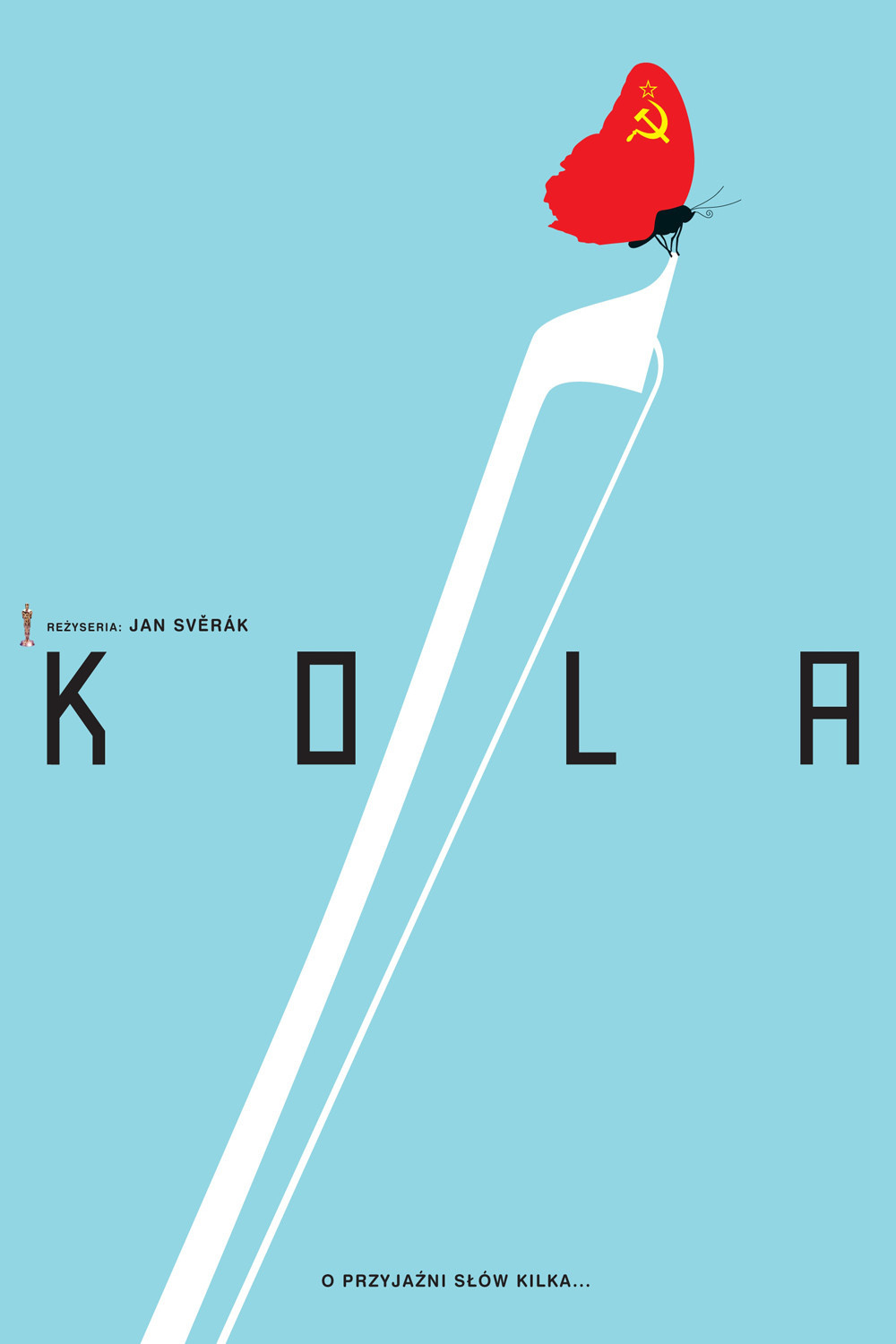

“Kolya” was written by its star, Zdenek Sverak, and directed by his son, Jan. It is a work of love, beautifully photographed by Vladimir Smutny in rich deep reds and browns, with steam rising from soup and the little boy looking wistfully at the pigeons on the other side of the tower window. It is said that American audiences are going to fewer foreign films these days. Missing a film like “Kolya,” winner of a 1997 Golden Globe, would not be a price I would be willing to pay.