Here is crucial dialogue from early in “Jackie Chan‘s First Strike”: “It’s me! I found new suspect!” “Who is he?” “I don’t know!” Right there you have the beauty of the Jackie Chan movies. He always finds the suspect. And he never quite knows what he’s doing. In its exotic locations and elaborate stunts, this could be a James Bond movie, if Bond were a cheerful Hong Kong cop who bumbles into the middle of the action by accident and fights his way out in sheer desperation.

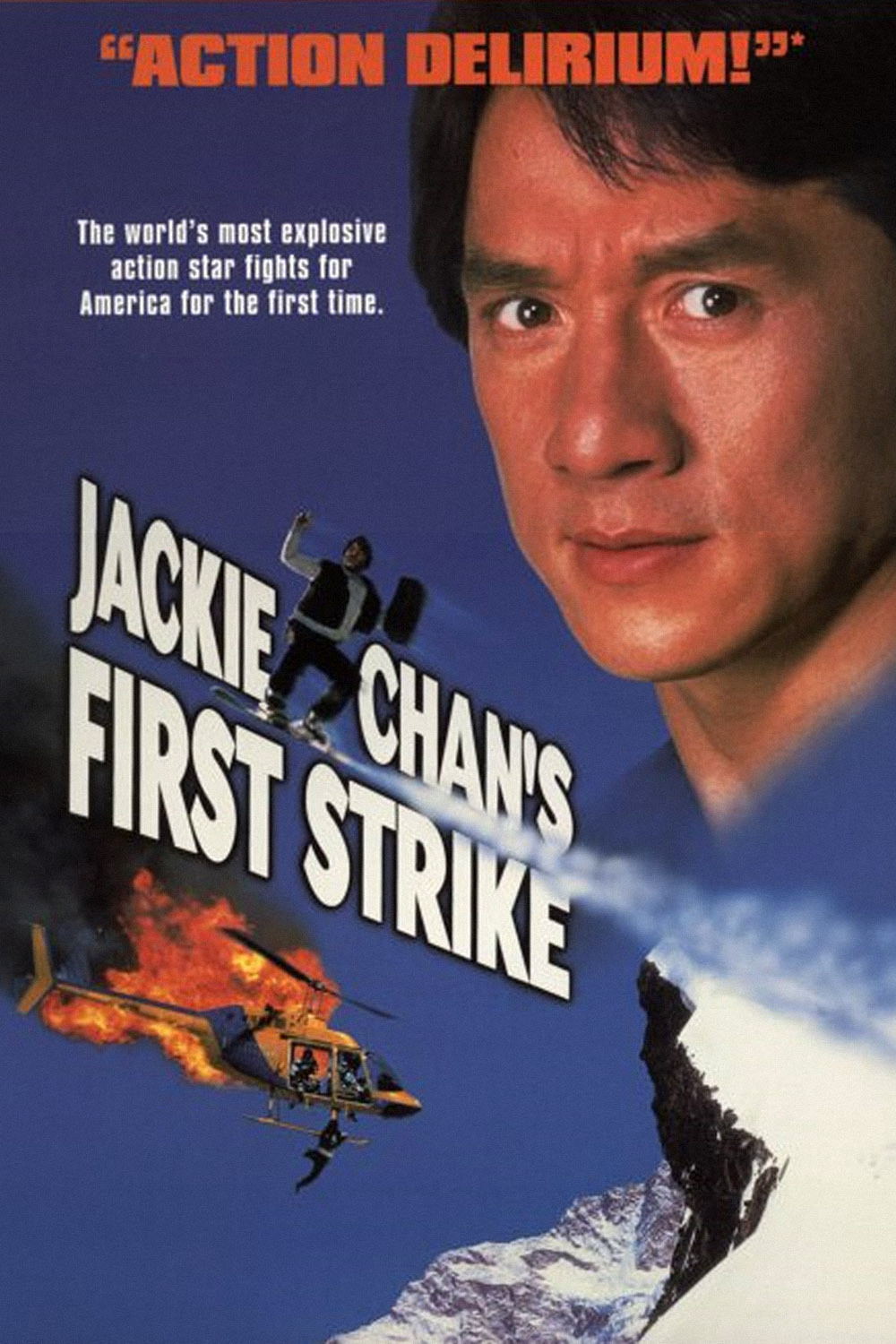

Chan is said to be the world’s top action star–except in the United States, which has resisted most of his 40-plus pictures. Now he is engaged in a campaign to conquer this last frontier; in 1996, we got “Rumble In The Bronx” and “Supercop,” and this year we get “Jackie Chan’s First Strike” and “Thunderbolt.” All are dubbed in English, mostly by Chan and the other actors themselves.

What makes him popular is not just his stunts (he is famous for doing them all himself) but his attitude while doing them: After a downhill ski chase in his shirt-sleeves, his teeth chatter. When he’s submerged in an icy lake, he desperately rubs his hands together for warmth. He wants our sympathy. And there is a sporting innocence in the action: Chan never uses a gun, there is no gore and not much blood, and he’d rather knock someone out than kill him.

The plot of “Jackie Chan’s First Strike” is surrealistic. Chan plays a Hong Kong cop named Jackie, who is assigned to follow the mysterious Natasha on a flight to Ukraine (he carefully makes a note every time she goes to the airplane toilet). In snow-covered Ukraine, he stumbles into a plot involving conspirators who want to steal the warhead of a nuclear missile.

Chan follows them into a forbidden military area. He sees a warning sign and shouts to his superiors over his cell phone, “It says trespassers will be shot!” “That’s just for kids,” his boss assures him. Then we get the downhill ski sequences, including one in which Chan skis off the side of a hill and grabs the runners of a helicopter. To be sure, it’s not a very big hill, and the helicopter is pretty close–but then we reflect that this is a real stunt, not a special effect, and we’re impressed by Chan’s skill and determination to entertain.

The “new KGB” surfaces, explains that the nuclear warhead is now in Australia, and that they are cooperating with the Hong Kong police. They will dispatch Chan to Brisbane–by submarine, which seems a rather slow way to get there. In Australia, Chan meets Annie (Chen Chun Wu), whose job is to enter an oceanarium tank to feed the sharks, and whose brother has stolen the warhead, which she hides for him in the shark tank.

This situation, of course, requires Chan to spend a lot of time just barely escaping being eaten by sharks, while snatching breaths of oxygen from his enemies’ scuba tanks. At one point my notes read: “New Russian Mafia terrorists fire rocket grenade at Chinese funeral in Brisbane,” which will give you the general idea, if you can also imagine the scene where a guy forces Chan to strip while singing “I Will Follow Him,” and then dresses him in a clown suit, after which Chan tries to operate a cellular phone while wearing porpoise flippers. A little later, Chan incapacitates a foe by flipping him into a tank filled with “toxic sea creatures,” which attach themselves to his body like mean little pin cushions.

Jackie Chan is an acquired taste. His movies don’t have the polish of big-budget Hollywood extravaganzas, the dialogue sounds like cartoon captions, and as the plot careens from Hong Kong to Ukraine to Australia, we realize that it was probably written specifically to sell well in Russia and Down Under. But Chan himself is a graceful and skilled physical actor, immensely likable, and there’s a kind of Boy Scout innocence in the action that’s refreshing after all the doom-mongering, blood-soaked Hollywood action movies. It’s as if the movie has been made of, by and for 13-year-old boys, and while you watch it you feel like one.