One of the first people the viewer meets in “Indian Point” is Brian Vangor, a nuclear engineer who’s been working at the Indian Point Energy Center, a nuclear power plant, for almost 40 years. Vangor is, as nuclear power plant workers go, kind of the anti-Homer Simpson. Soft-spoken, knowledgeable, conscientious, calm. He is the Senior Control Room Operator at the plant and he seems to know well what he’s on about. He’s the kind of guy, in other words, who you definitely want overseeing such an operation. And he believes in what he does. “This technology has its problems,” he asserts, “But show me a technology that doesn’t.”

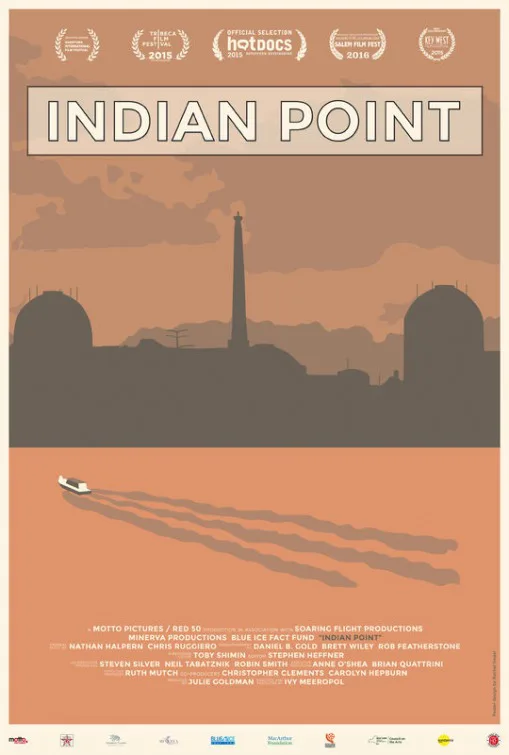

Of course, the potential problems of nuclear energy are decidedly different from any other form of energy. This point was brought home by the multiple meltdowns at Japan’s Fukushima plant after an earthquake and attendant tsunami in 2011. Japan, and the world, is still feeling the effects of that disaster, and the event gave new motivation and energy to the residents of the town Indian Point. Just thirty miles away from the New York metropolitan area, the Indian Point plant is operated by a company called Entergy, and its license was up for renewal shortly after the Fukushima event. Writer/director Ivy Meerpool’s engrossing documentary profiles local activists and journalists—in this case, specifically, an activist and a journalist who are also a married couple—while looking at the bigger picture via the story of Gregory Jaczko, the onetime head of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission who, by this movie’s reckoning, was forced out of his position by a ginned-up scandal after his post-Fukushima recommendations for safety chafed the actual energy industry.

Meerpool’s movie is scary without being alarmist; it notes, of course, the fact that Indian Point has operated without a Fukushima type event for over two decades, but it also quietly says that SHOULD a Fukushima type event ever occur there, I myself probably won’t be around to write a review that’s critical of nuclear energy. While the profiles of folks like Vangor provide a certain even-handedness, the movie does have an agenda, and it’s helped when someone like Jim Steets, the spokesman for Entergy, shows up on screen. He’s very professional, maybe too professional: were one in the mood to be unkind, one would note that his whole manner practically screams “corporate hack” in mere nanoseconds.

Jaczko, on the other hand, is portrayed as a conscientious public servant whose initial mission was hardly to rule out the nuclear option, but who is persuaded by what he witnesses in Japan to say, at one point, “Maybe [we need to] shut down all the plants.” Interesting idea, given that there are almost 450 online in the world now.

Even as it evokes terrifying dangers, the movie holds out hope. As Jaczko points out, even as space-age energy goes, nuclear is pretty old-school and probably on the way out. On the other hand, the energy industry as it’s currently constituted is digging its heels in: it wants what it wants, and productively moving forward is not really a priority. This, combined with things such as “spent fuel pools,” which this movie describes in some disquieting details, are invoked by the filmmakers to send a message to the viewer: change isn’t going to happen without constant citizen vigilance and activism.