Robert Aldrich’s “Hustle” is the kind of many-layered, complex, cynical crime story we get more often these days in novels than in movies. Maybe that’s because novels (especially the Ross Macdonald books) like to relish their atmosphere more, to fool around with mood and provide a certain style for the dialog and characters.

Crime movies used to do that, too — it used to be their specialty — but in recent years a lot of cop and private eye movies have collapsed into set pieces for violence. We get shoot-outs, bloody death and high-speed chases, all handled with such mechanistic efficiency that we can’t tell one movie from another.

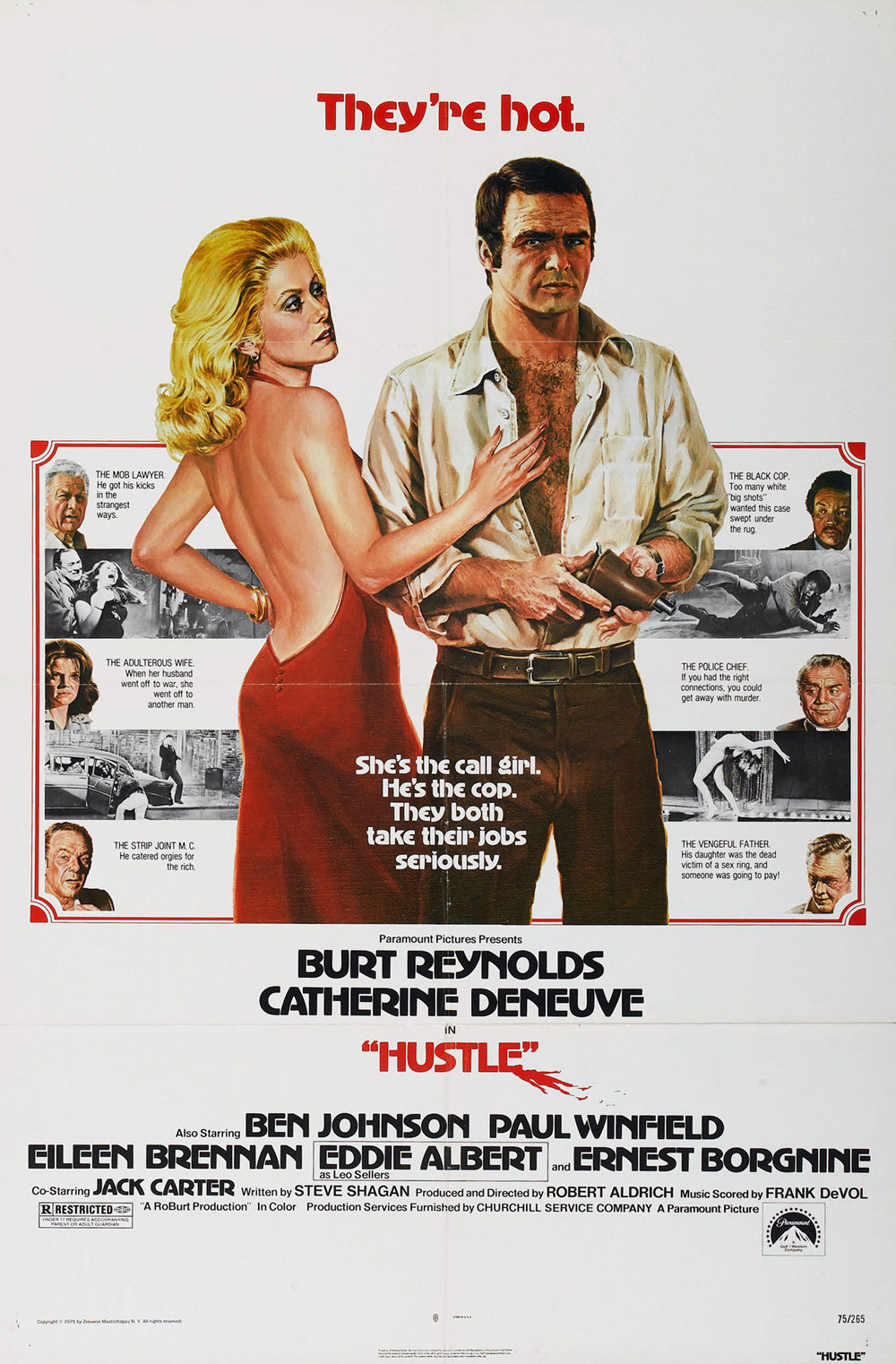

“Hustle” isn’t like that. It’s a movie about characters, primarily. It cares more about getting inside these people than it does about solving its crime. And the two leading characters, a Los Angeles police lieutenant and a French prostitute, become unexpectedly interesting because they’re made into such individuals by Burt Reynolds and Catherine Deneuve. Sure, the characters sound like clichés — the cop and the hooker — and on the basis of their track records, we wouldn’t necessarily expect Reynolds or Deneuve to transform them. They’ve played their share of fairly routine cops and whores before; it’s a house specialty. But this time they create an involved, absorbing relationship that works.

We meet them in bed. We see a lot of them in bed, in fact, and it would be less than honest not to admit that Reynolds and Deneuve — despite all the old jokes about his Cosmopolitan centerfold and her Chanel ads — are uncommonly attractive people. But Aldrich doesn’t just photograph them, he uses them: Deneuve for the tantalizing aura of icy kinkiness that came through in “Belle de Jour” and “Tristana,” and Reynolds for the humor and vulnerability he mixes in with his virility.

She’d get out of the business in a moment if he’d marry her, she says, although there’s a certain fascinating detachment about the way she takes $100 dirty phone calls and spends afternoons on the yachts of rich lawyers. He’d marry her, except he’s on the rebound from a bad marriage, and, besides, she’s a hooker.

They almost get this difficulty worked out, but some problems intervene. A girl is found dead beside a swimming pool and the rich lawyer (played by Eddie Albert with that Middle American savagery he has perfected recently) is implicated. The girl’s father (Ben Johnson) is convinced that murder is involved. He accuses the cops of being on the take.

What they know and he doesn’t is that the girl had been involved for three years as a prostitute, porno movie star and Sunset Strip stripper and that she almost certainly committed suicide. Reynolds and his partner (Paul Winfield, who played the father in “Sounder“) circle around this case while handling whatever else comes up, like a homicidal killer holding hostages. They also drink a lot of Bushmill’s Irish Whiskey, which is referred to by name so often it’s like Paul Newman ordering a Coors.

It’s in the secondary characters that the movie begins to take on a richness of texture we weren’t really expecting. Johnson has never quite been the same, we learn, since he came back from Korea. He lived for his daughter. His wife (Eileen Brennan) is worried that he might try something foolish, and she’s right. He tracks his daughter’s trail through seedy strip clubs (seen by Aldrich in just the right sad light) and finds his way to the rich lawyer. Now it happens that the lawyer, Albert, is the man who helped Deneuve get a visa to America in the first place. Reynolds knows this. In fact, he knows Albert is still one of Deneuve’s clients. Reynolds thinks he’s hard-boiled enough, cynical enough that this doesn’t bother him, but it does. And yet he knows Albert didn’t kill Johnson’s daughter: “He’s killed other people, but he didn’t do this one.” His partner is the one person he can confide in; he and Winfield sit around the station a lot, buying each other drinks out of the office bottle.

And we begin to realize that there’s really a mystery involved here. The girl did commit suicide. The lawyer didn’t kill her. The problem is with the father, but Reynolds believes he can handle him. “Hustle” develops as a movie about its characters, rather than about any crime they’ve got to solve. It’s not as linear as routine cop thrillers. It’s got a lot of weariness and humor, largely due, I’m sure, to the screenplay by Steve (“Save the Tiger“) Shagan. Aldrich, who’s an old hand at seedy urban melodrama (his credits include “Kiss Me Deadly” and “The Big Knife”) never gets too cute and never gets too dull: He’s found the right note. And in the movie’s center, circling warily, are Reynolds and Deneuve, both so worn, so worldly, so cynical, they don’t even realize what total romantics they are.