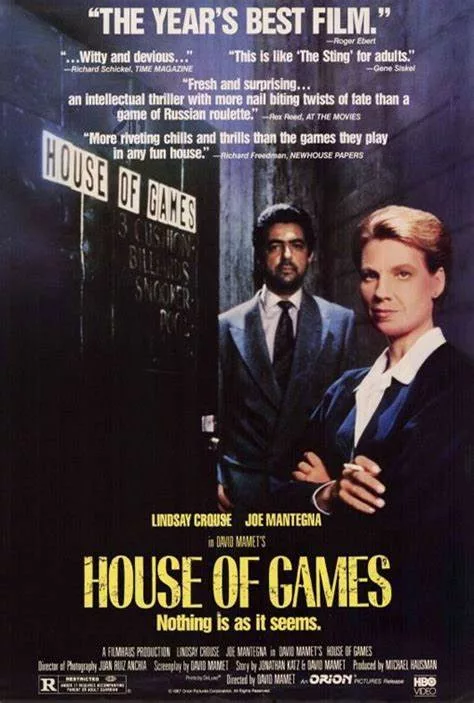

This movie is awake. I have seen so many films that were sleepwalking through the debris of old plots and second-hand ideas that it was a constant pleasure to watch “House of Games,” a movie about con men that succeeds not only in conning the audience, but also in creating a series of characters who seem imprisoned by the need to con, or be conned.

The film stars Lindsay Crouse as a psychiatrist who specializes in addictive behavior, possibly as a way of dealing with her own compulsions. One of her patients is a gambler who fears he will be murdered over a bad debt.

Crouse walks through lonely night streets to the neon signs of the House of Games, a bar where she thinks she can find the gambler who has terrorized her client. She wants to talk him out of enforcing the debt.

The gambler (Joe Mantegna) has never heard anything like this before. But he offers her a deal: If she will help him fleece a high-roller Texan in a big-stakes poker game, he will tear up the marker. She does so. She also becomes fascinated by the backroom reality of these gamblers who have reduced life to a knowledge of the odds. She comes back the next day, looking for Mantegna. She tells him she wants to learn more about gamblers and con men, about the kind of man that he is. By the end of this movie, does she ever.

“House of Games” was written and directed by David Mamet, the playwright (“Glengarry Glen Ross“) and screenwriter (“The Untouchables“), and it is his directorial debut. Originally it was intended as a big-budget movie with an established director and major stars, but Mamet took the reins himself, cast his wife in the lead and old acting friends in the other important roles, and shot it on the rainy streets of Seattle. Usually the screenwriter is insane to think he can direct a movie. Not this time. “House of Games” never steps wrong from beginning to end, and it is one of this year’s best films.

The plotting is diabolical and impeccable, and I will not spoil the delight of its unfolding by mentioning the crucial details. What I can mention are the performances, the dialogue and the setting. When Crouse enters the House of Games, she enters a world occupied by characters who have known each other so long and so well, in so many different ways, that everything they say is a kind of shorthand. At first we don’t fully realize that, and there is a strange savor to the words they use.

They speak, of course, in Mamet’s distinctive dialogue style, an almost musical rhythm of stopping, backing up, starting again, repeating, emphasizing, all of the time with the hint of deeper meanings below the surfaces of the words. The leading actors, Chicagoans Mantegna and Mike Nussbaum, have appeared in countless performances of Mamet plays over the years, and they know his dialogue the way other actors grow into Beckett or Shakespeare. They speak it as it is meant to be spoken, with a sort of aggressive, almost insulting directness.

Mantegna has a scene where he “reads” Crouse – where he tells her about her “tells,” those small giveaway looks and gestures that poker players use to read the minds of their opponents. The way he talks to her is so incisive and unadorned it is sexual.

These characters and others live in a city that looks, as the Seattle of “Trouble in Mind” did, like a place on a parallel time track. It is a modern American city, but none we have quite seen before; it seems to have been modeled on the paintings of Edward Hopper, where lonely people wait in empty public places for their destinies to intercept them. Crouse is portrayed as an alien in this world, a successful, best-selling author who has never dreamed that men like this exist, and the movie is insidious in the way it shows her willingness to be corrupted.

There is in all of us a fascination for the inside dope, for the methods of the confidence game, for the secrets of a magic trick. But there is an eternal gulf between the shark and the mark, between the con man and his victim. And there is a code to protect the secrets. There are moments in “House of Games” when Mantegna instructs Crouse in the methods and lore of the con game, but inside every con is another one.

I met a woman once who was divorced from a professional magician. She hated this man with a passion. She used to appear with him in a baffling trick where they exchanged places, handcuffed and manacled, in a locked cabinet. I asked her how it was done. The divorce and her feelings meant nothing compared to her loyalty to the magical profession. She looked at me coldly and said, “The trick is told when the trick is sold.” The ultimate question in “House of Games” is, who’s buying?