A film like “Hoop Dreams” is what the movies are for. It takes us, shakes us, and make us think in new ways about the world around us. It gives us the impression of having touched life itself.

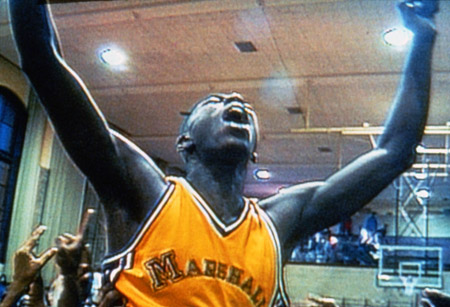

“Hoop Dreams” is, on one level, a documentary about two African-American kids named William Gates and Arthur Agee, from Chicago’s inner city, who are gifted basketball players and dream of someday starring in the NBA. On another level, it is about much larger subjects: about ambition, competition, race and class in our society. About our value structures. And about the daily lives of people like the Agee and Gates families, who are usually invisible in the mass media, but have a determination and resiliency that is a cause for hope.

The movie spans six years in the lives of William and Arthur, starting when they are in the eighth grade, and continuing through the first year of college. It was intended originally to be a 30-minute short, but as the filmmakers followed their two subjects, they realized this was a much larger, and longer story. And so we are allowed to watch the subjects grow up during the movie, and this palpable sense of the passage of time is like walking for a time in their shoes.

They’re spotted during playground games by a scout for St. Joseph’s High School in west suburban Westchester, a basketball powerhouse. Attending classes there will mean a long daily commute to a school with few other black faces, but there’s never an instant when William or Arthur, or their families, doubt the wisdom of this opportunity: St. Joseph’s, we hear time and again, is the school where another inner-city kid, Isiah Thomas, started his climb to NBA stardom.

One image from the film: Gates, who lives in the Cabrini Green project, and Agee, who lives on Chicago’s South Side, get up before dawn on cold winter days to begin their daily 90-minute commute to Westchester. The street lights reflect off the hard winter ice, and we realize what a long road – what plain hard work – is involved in trying to get to the top of the professional sports pyramid. Other high school students may go to “career counselors,” who steer them into likely professions. Arthur and William are working harder, perhaps, than anyone else in their school – for jobs which, we are told, they have only a .00005 percent chance of winning.

We know all about the dream. We watch Michael Jordan and Isiah Thomas and the others on television, and we understand why any kid with talent would hope to be out on the same courts someday. But “Hoop Dreams” is not simply about basketball. It is about the texture and reality of daily existence in a big American city. And as the film follows Agee and Gates through high school and into their first year of college, we understand all of the human dimensions behind the easy media images of life in the “ghetto.”

We learn, for example, of how their extended families pull together to help give kids a chance. How if one family member is going through a period of trouble (Arthur’s father is fighting a drug problem), others seem to rise to periods of strength. How if some family members are unemployed, or if the lights get turned off, there is also somehow an uncle with a big back yard, just right for a family celebration. We see how the strong black church structure provides support and encouragement – how it is rooted in reality, accepts people as they are, and believes in redemption.

And how some people never give up. Arthur’s mother asks the filmmakers, “Do you ever ask yourself how I get by on $268 a month and keep this house and feed these children? Do you ever ask yourself that question?” Yes, frankly, we do. But another question is how she finds such determination and hope that by the end of the film, miraculously, she has completed her education as a nursing assistant.

“Hoop Dreams” contains more actual information about life as it is lived in poor black city neighborhoods than any other film I have ever seen.

Because we see where William and Arthur come from, we understand how deeply they hope to transcend – to use their gifts to become pro athletes. We follow their steps along the path that will lead, they hope, from grade school to the NBA.

The people at St. Joseph’s High School are not pleased with the way they appear in the film, and have filed suit, saying among other things that they were told the film would be a non-profit project to be aired on PBS, not a commercial venture. The filmmakers respond that they, too, thought it would – that the amazing response which has found it a theatrical release is a surprise to them. The movie simply turned out to be a masterpiece, and its intended non-commercial slot was not big enough to hold it. The St. Joseph suit reveals understandable sensitivity, because not all of the St.

Joseph people come out looking like heroes.

It is as clear as night and day that the only reason Arthur Agee and William Gates are offered scholarships to St. Joseph’s in the first place is because they are gifted basketball players. They are hired as athletes as surely as if they were free agents in pro ball; suburban high schools do not often send scouts to the inner city to find future scientists or teachers.

Both sets of parents are required to pay a small part of the tuition costs. When Gates’ family cannot pay, a member of the booster club pays for him – because he seems destined to be a high school all-American. Arthur at first does not seem as talented. And when he has to drop out of the school because his parents have both lost their jobs, there is no sponsor for him. Instead, there’s a telling scene where the school refuses to release his transcripts until the parents have paid their share of his tuition.

The morality here is clear: St. Joseph’s wanted Arthur, recruited him, and would have found tuition funds for him if he had played up to expectations.

When he did not, the school held the boy’s future as hostage for a debt his parents clearly would never have contracted if the school’s recruiters had not come scouting grade school playgrounds for the boy. No wonder St. Joseph’s feels uncomfortable. Its behavior seems like something out of Dickens. The name Scrooge comes to mind.

Gene Pingatore, the coach at St. Joseph’s, is a party to the suit (which actually finds a way to plug the Isiah Thomas connection). He feels he’s seen in an unattractive light. I thought he came across fairly well. Like all coaches, he believes athletics are a great deal more important than they really are, and there is a moment when he leaves a decision to Gates that Gates is clearly not well-prepared to make. But it isn’t Pingatore but the whole system that is brought into question: What does it say about the values involved, when the pro sports machine reaches right down to eighth-grade playgrounds?

But the film is not only, or mostly, about such issues. It is about the ebb and flow of life over several years, as the careers of the two boys go through changes so amazing that, if this were fiction, we would say it was unbelievable. The filmmakers (Steve James, Frederick Marx and Peter Gilbert) shot miles of film, 250 hours in all, and that means they were there for several of the dramatic turning-points in the lives of the two young men. For both, there are reversals of fortune – life seems bleak, and then is redeemed by hope and sometimes even triumph. I was caught up in their destinies as I rarely am in a fiction thriller, because real life can be a cliff-hanger, too.

Many filmgoers are reluctant to see documentaries, for reasons I’ve never understood; the good ones are frequently more absorbing and entertaining than fiction. “Hoop Dreams,” however, is not only a documentary. It is also poetry and prose, muckraking and expose, journalism and polemic. It is one of the great moviegoing experiences of my lifetime.