Marine Sgt. Nathan Harris is a natural leader of men. We sense that during the extraordinary combat footage in “Hell and Back Again,” not because he behaves heroically or makes eloquent speeches, but because he knows his job and believes in it. He’s in his mid-20s, sometimes looks and sounds younger, and yet his sense of mission carries him forward and we understand why men would follow him into danger. He seems to be a good man, brave, uncomplicated.

Near the end of a six-month tour in Afghanistan, a sniper’s bullet “blows half his ass off,” as he puts it in “Hell and Back Again,” one of this year’s nominees for the best documentary Oscar. He is not shy about describing his wound. More than once during this film he pulls down his belt to allow people to see the crater left on his right hip by a bullet, and then he explains how it penetrated to his hip socket, “messed that up” and bounced off to shatter his leg lower down. The first time he explains this, he is sitting in a battery-powered cart in a Wal-Mart, talking to an elderly woman shopper in a matching cart. “Can I give you a hug?” she says, and his smile suggests how much backed-up tension that released.

Harris was lucky not to be paralyzed. He is disappointed to learn that it will take him a year of rehab before he can think about going into combat again. We privately understand his combat days are in the past. Hasn’t he paid his dues? He doesn’t think so. We don’t know him well enough. Even when he was a kid, he says, he wanted a job where he could kill people. That’s why he enlisted in the Marines at 18. Now he’s done a little growing up, he reflects, and things no longer seem that simple.

In Afghanistan, he clearly believes in the U.S. mission from deep in his heart. There are three scenes where he talks with village elders through a translator, explaining how he and fellow Americans are there to bring them freedom. The elders are not convinced. The American and the Taliban are all the same to them, destroying crops, disrupting rural life, causing many to flee from areas altogether. They seem to have no love for the Taliban, but foreigners come and go and the Taliban is always there.

Director Danfung Dennis, a photojournalist, carried one of the new compact Canon cameras into the field with Harris’ Echo Company, following them on foot as they run across fields and proceed gingerly into villages. Some are point-of- view shots of a man crawling on his stomach under fire — as Dennis was doing. We never actually see a Taliban fighter, but they’re out there. On Echo Company’s first day, they lose a Marine. Later comes the wound that changes Harris’ life.

He returns home to North Carolina and his wife, Ashley, his high school sweetheart. She is lovely, sweet, patient. After surgery and rehab, her husband is released to her care, and we see her at a Walgreens prescription counter, buying enough pills so that the orange plastic bottles fill a Zip-Loc bag. One contains Vicodin. Some wounded soldiers who miss dying in combat are struck down by prescribed medication.

Harris uses a wheelchair and then an aluminum walker to get around. He talks about trying again and again to take three steps on his own, falling, and trying again. He and Ashley have a quiet home life that seems sad to me, because if he cannot go into battle, an essential part of him has been lost. There are times, she says, when it’s like he’s become different man.

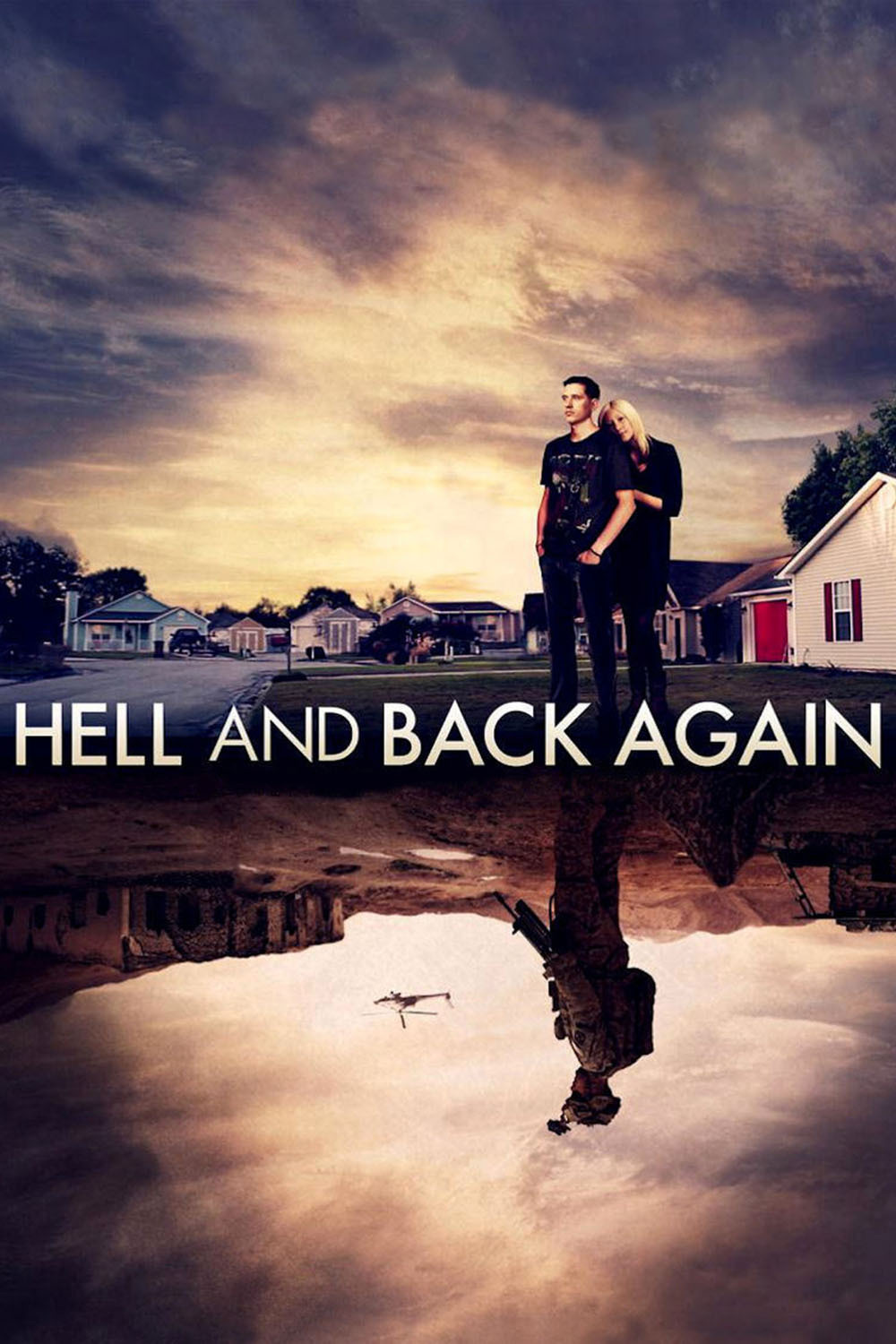

“Hell and Back Again” presents his new reality with a stunningly good use of video and sound editing. His life at home, its sights and sounds, are intercut with his life in Afghanistan. His war memories are always with him, and in some respects, seem more real than his home life. He was never a full-time husband, we sense; he was a soldier home on leave.

In its closing scenes, “Hell and Back Again” builds to an emotional and stylistic power that we didn’t see coming. In the darkness of night, in pillow talk, Nathan tells Ashley of the thoughts and memories that haunt his dreams. We realize she has her own kind of heroism in standing by this man. He was most fully alive when he was leading his men into combat; he believed in his usefulness and the worth of his mission. Now that he cannot serve and can barely walk, he is beginning to understand how much he has lost. He hasn’t lost only the full use of a leg. He has lost the full use of himself.