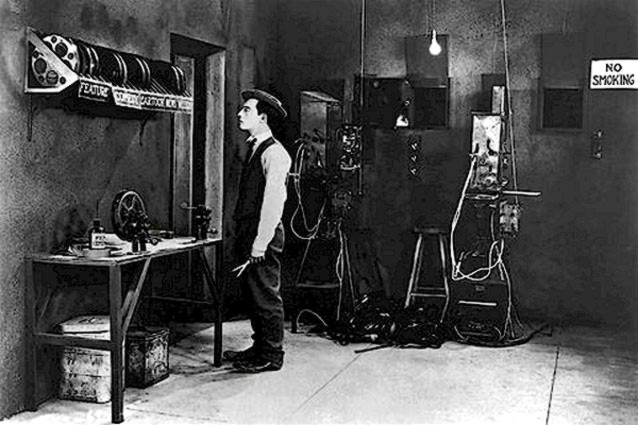

The greatest of the silent clowns is Buster Keaton, not only because of what he did, but because of how he did it. Harold Lloyd made us laugh as much, Charlie Chaplin moved us more deeply, but no one had more courage than Buster. I define courage as Hemingway did: “Grace under pressure.” In films that combined comedy with extraordinary physical risks, Buster Keaton played a brave spirit who took the universe on its own terms, and gave no quarter.

I’m immersed in his career right now, viewing all of the silent features and many of the shorts with students at the University of Chicago. Having already written about Keaton’s “The General” (1927) in this series, I thought to choose another title. “The Navigator,” perhaps, or “Steamboat Bill, Jr.,” or “Our Hospitality.” But they are all of a piece; in an extraordinary period from 1920 to 1929, he worked without interruption on a series of films that make him, arguably, the greatest actor-director in the history of the movies.

Most of these movies were long thought to be lost. “The General,” with Buster as a train engineer in the Civil War, was always available, hailed as one of the supreme masterpieces of silent filmmaking. But other features and shorts existed in shabby, incomplete prints, if at all, and it was only in the 1960s that film historians began to assemble and restore Keaton’s lifework. Now almost everything has been recovered, restored, and is available on DVDs and tapes that range from watchable to sparkling.

It’s said that Chaplin wanted you to like him, but Keaton didn’t care. I think he cared, but was too proud to ask. His films avoid the pathos and sentiment of the Chaplin pictures, and usually feature a jaunty young man who sees an objective and goes after it in the face of the most daunting obstacles. Buster survives tornadoes, waterfalls, avalanches of boulders and falls from great heights, and never pauses to take a bow: He has his eye on his goal. And his movies, seen as a group, are like a sustained act of optimism in the face of adversity; surprising how, without asking, he earns our admiration and tenderness.

Because he was funny, because he wore that porkpie hat, Keaton’s physical skills are often undervalued. We hear about the stunts of Douglas Fairbanks Sr., but no silent star did more dangerous stunts than Buster Keaton. Instead of using doubles, he himself doubled for some of his actors, doing their stunts as well as his own.

He said he learned to “take a fall” as a child, when he toured in vaudeville with his parents, Joe and Myra. By the time he was 3, he was being thrown around the stage and into the orchestra pit, and his little suits even had a handle concealed at the waist, so Joe could sling him like luggage. Today this would be child abuse; then it was showbiz. “It was the roughest knockabout act that was ever in the history of the theater,” Keaton told the historian Kevin Brownlow. He claimed that Harry Houdini dubbed him “Buster” because of those falls; Houdini was a friend, but the nickname came before the Keatons met him.

Buster and Joe discovered that when he was hurled through the bass drum and emerged waving and smiling, the audience didn’t see the joke in treating a kid that way. But when Buster emerged with a solemn expression on his face, for some reason the audience loved it. For the rest of his career, Keaton was “the great stone face,” with an expression that ranged from the impassive to the slightly quizzical.

He falls and falls and falls in his movies: From second-story windows, cliffs, trees, trains, motorcycles, balconies. The falls are usually not faked: He lands, gets up, keep going. He was one of the most gifted stuntmen in the movies. Even when there is fakery, the result is daring; in “Go West” he seems to fall from a high suspension bridge, but actually falls only 50 feet or so before landing in a net; there’s a cut to another shot showing him falling the last 20 feet. Both halves of this “faked” stunt are dangerous. And in “Our Hospitality,” where he was almost killed when a safety wire snapped and he was swept toward a waterfall, he finished the sequence with a fake waterfall–but even it was 25 feet high, and he’s swinging above a nasty fall.

Keaton is famous for a shot in “Steamboat Bill, Jr.,” where he stands in front of a house during a cyclone, and a wall falls on top of him; he is saved because he happens to be exactly where the window is. There was scant clearance on either side, and you can see his shoulders tighten a little just as the wall lands. He refused to rehearse the stunt because, he explained, he trusted his set-up, so why waste a wall?

In film after film, Keaton does difficult and dangerous things and keeps the poker face. His philosophy is embodied in his body language: The world throws its worst at him, but he is plucky and determined, ingenious and stubborn, and will do his best. Walter Kerr, in his definitive book “The Silent Clowns,” writes of Keaton’s “stillness of emotion as well as body, a universal stillness that comes of things functioining well, of having achieved harmony.” When Harold Lloyd dangled from a clock face far above the street, he intended to terrify his audience. When Keaton sat on the front of a moving locomotive in “The General” and attempted to knock one railroad tie off the tracks with another, he could have been crushed beneath the train, but he presents the action as a strategy, not a stunt.

Kerr talks of the “Keaton Curve,” the way an action ends up where it began. There’s a shot in the early short “Neighbors” where Keaton escapes a house via a clothesline, swings safely across to his own house–then finds that the clothesline keeps rotating, depositing him right back in trouble. In “The General,” there are innumerable examples of the Curve, for example a scene where the train goes around a bend so that a cannon now points at Buster instead of the enemy. You can also see the Curve in many of those scenes where he invents ingenious “labor-saving” devices–to serve breaskfast, for example. One of his funniest shorts is “The Scarecrow,” which includes a house where everything–table, bed, stove–has more than one function, so that a meal consists of a tour through the parabola of the house’s gadgets.

Another of Keaton’s strategies was to avoid anticipation. Instead of showing you what was about to happen, he showed you what was happening; the surprise and the response are both unexpected, and funnier. He also gets laughs by the application of perfect logic. In “Our Hospitality,” he discovers he is in the house of a family sworn to kill him. But Southern Hospitality insists they cannot shoot a visitor in their own house. So Buster invites himself to spend the night.

In the last decade of silent film, Keaton worked as an independent auteur. He usually used the same crew, worked with trusted riggers who understood his thinking, conceived his screenplays mostly by himself. He had backing from the mogol Joe Schenck (they were brothers-in-law, both married to Talmadge girls), but Schenck sometimes missed the point. He was outraged that Buster spent $25,000 to buy the ship used in “The Navigator,” but then. without consulting Keaton, spent $25,000 to buy the rights to a third-rate Broadway farce that Buster somehow transformed into “Seven Chances.”

Like Chaplin and Lloyd, he was a perfectionist who would reshoot sequences until the laughs worked, would take as long as necessary on a single shot, would supervise every element of his films. No filmmaker has ever had a better run of genius than Keaton during that decade. But then talkies came in, and he made “the biggest mistake of my life,” signing on with MGM for a series of sound comedies that mostly made money, but were not under his personal control. He didn’t like them.

By the late 1930s, Buster Keaton (1895-1966) was out of business as a self-starting auteur. He continued to work all his life, doing innumerable TV appearances and turning up in movies like Chaplin’s “Limelight,” Wilder’s “Sunset Boulevard” and even “Film,” an original screenplay by Samuel Beckett. He lived in the San Fernando Valley, raised chickens, and thought his work had been forgotten. Then came a 1962 retrospective at the Cinematheque Francaise in Paris, and a tribute at the 1965 Venice Film Festival. He was relieved to see that his films were not after all lost, but observed, no doubt with a stone face, “The applause is nice, but too late.”