All movies toy with us, but the best ones have the nerve to admit it. Most movies pretend their stories are real and that we must take them seriously. Comedies are allowed to break the rules. Most of the films of Luis Bunuel are comedies in one way or another, but he doesn’t go for gags and punch lines; his comedy is more like a dig in the ribs, sly and painful.

Consider two of his best films side-by-side. “The Exterminating Angel” (1962) is about a group of guests who arrive for dinner, enjoy it and then cannot leave. They’re mysteriously compelled to spend days and weeks squatting in the house of their host. Civilized behavior erodes as the press and the police gather helplessly outside. Now look at “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” (1972), about people who are trapped on the other side of the mirror: They constantly arrive for dinner and sometimes even sit down for it, but are never able to eat. They arrive on the wrong night, or are alarmed to find the corpse of the restaurant owner in the next room, or are interrupted by military maneuvers.

Dinner is the central social ritual of the middle classes, a way of displaying wealth and good manners. It also offers the convenience of something to do (eat) and something to talk about (the food), and that is a great relief, since so many of the bourgeoisie have nothing much to talk about, and there are a great many things they hope will not be mentioned. The joke in “The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” is the way Bunuel interrupts the meals with the secrets that lurk beneath the surface of his decaying European aristocracy: witlessness, adultery, drug dealing, cheating, military coups, perversion and the paralysis of boredom. His central characters are politicians, the military and the rich, but in a generous mood he throws in a supporting character to make fun of the church–a bishop whose fetish is to dress up as a gardener and work as a servant in the gardens of the wealthy.

“The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” was Bunuel’s most successful film; it made more money even than his famous “Belle de Jour” (1967), won the Oscar as best foreign film and was named the year’s best by the National Society of Film Critics. It was released in a year when social unrest was at its height, the Vietnam War was in full flower, and the upper middle class was a fashionable target of disdain. How different to see it again in 2000, when affluence is once again praised and envied. The primary audience for the film in 1972 saw it as attacking others; the primary audience today will, if it is perceptive, see it as an attack on itself.

Bunuel (1900-1983), a Spaniard who worked in Mexico, Hollywood and Spain before returning at last to his homeland, was a surrealist in the 1920s (he collaborated with Salvador Dali on “Un Chien Andalou,” probably the most famous short film ever made). He spent years in political, financial and artistic exile, and many of his Mexican films were done for hire, but he always managed to make them his own, with his anarchic disrespect for authority and his jaundiced view of human nature. His characters are often selfish and self-centered, willing to compromise any principle in order to find gratification. Even when he makes a movie like “Simon of the Desert” (1965), about the saint who lived for 37 years atop a pillar, he finds him motivated by his ego; Simon likes the crowds he draws.

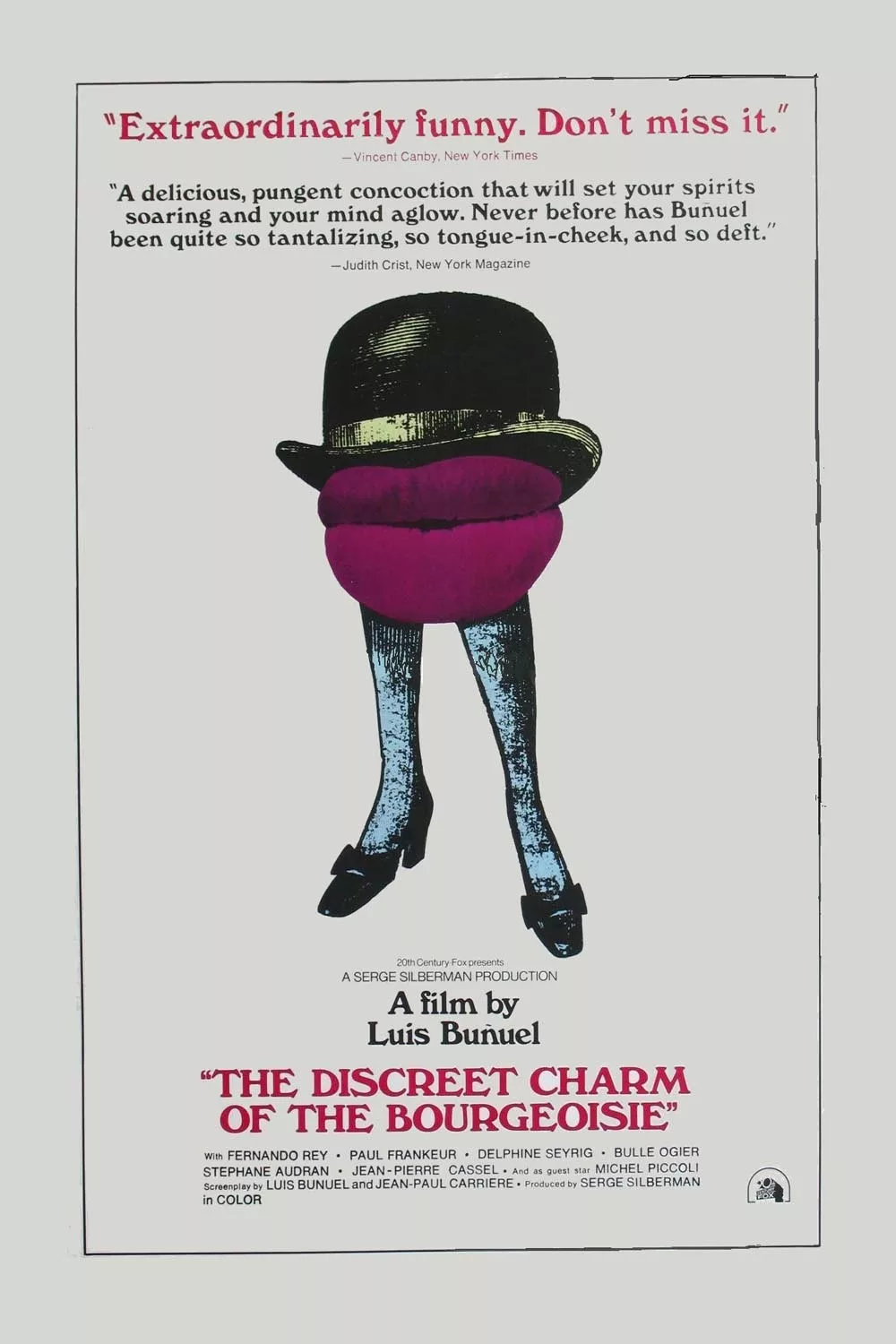

From the first shots of “Discreet Charm,” we are aware of the way his characters carry themselves. They exude their status; they are sure of who they are, and wear their position in society like a costume. Fernando Rey’s little peacock of an ambassador, Stephane Audran’s rich hostess, Bulle Ogier’s bored and alcoholic sister–all act as if they’re playing roles. And consider the bishop (Julien Bertheau), who appears at the door in gardener’s clothes and is scornfully turned away, only to reappear in his clerical garb to “explain himself,” and be embraced. In Bunuel the clothes not only make the man, but are the man (especially true for a director with lifelong fetishes involving clothes and shoes).

The movie is broken into self-contained sequences, showing the bland surface of polite society and the lusts that lurk beneath. A couple expects guests for dinner. In the bedroom, they are overcome by lust. The guests arrive. Now they cannot make love in the bedroom because the wife “makes too much noise,” the husband complains, so they sneak out a window and passionately couple in the woods. Then they sneak back into the house, leaves and grass in their hair. Bourgeoisie manners, Bunuel believes, are the flimsiest facade for our animal natures. Another example: After soldiers open fire on dinner guests, a man escapes death by hiding under a table, but betrays himself by greedily reaching up for the meat still on his plate.

The film’s narrative flow is cheerfully shattered by Bunuel’s devices. As women have drinks in a garden cafe, a lieutenant walks over and begins a harrowing tale of childhood. We see his story in flashback. He finishes, bids them good day, and leaves. A dinner party develops strangely when the roast chickens are dropped by the servant and turn out to be stage props–and then the curtain goes up and the guests find themselves on stage before an audience. Dreams fold within dreams, not because the characters are confused, but because Bunuel is amusing himself by using such obvious tricks.

The movie is not savage or angry, but bemused and cynical. Bunuel was 72 when he directed it. “It belongs both to his old age and to his second childhood,” says A.O. Scott. Backed by the French producer Serge Silberman, he was free at last to indulge his fancies, and “Discreet Charm” is liberated from any commercial or narrative requirement. A few years later, with “That Obscure Object of Desire,” he actually had two actresses play the same role, without any explanation. All of these later films were written by Jean-Claude Carriere, who also helped on Bunuel’s autobiography, and who shared the master’s conviction that hypocrisy was the most entertaining target.

The year 2000 is Bunuel’s centenary. Rialto Pictures is marking the milestone with releases of restored prints not only of “Discreet Charm” (which also has new subtitles) but also “Diary of a Chambermaid” (1970), with Jeanne Moreau; “The Milky Way” (1970), with its pilgrims on a perplexing spiritual odyssey; “That Obscure Object of Desire” (1977), and “The Phantom of Liberty” (1974), with its famous scene where dinner guests defecate in public but sneak off alone in order to eat–Bunuel wickedly suggests that the two activities are, in some fundamental way, equivalent.

Of all the things he found hilarious, Bunuel was perhaps most amused by fetishes. To him, sex was something we take seriously when it involves ourselves and ribald when it involves others. What’s more hilarious than someone saddled with a fetish that is absurd, inconvenient or not respectable? Consider the situation in “Tristana,” where the woman with one leg (Catherine Deneuve) cruelly and knowledgeably toys with the servant boy who is fascinated by her disability.

His films constitute one of the most distinctive bodies of work in the first century of films. Bunuel was cynical, but not depressed. We say one thing and do another, yes, but that doesn’t make us evil–only human and, from his point of view, funny. He has been called a cruel filmmaker, but the more I look at his films the more wisdom and acceptance I find. He sees that we are hypocrites, admits to being one himself and believes we were probably made that way.