Shukichi is a professor, a widower, absorbed in his work. His unmarried daughter, Noriko, runs his household for him. Both are perfectly content with this arrangement until the old man’s sister declares that her niece should get married. Noriko is, after all, in her mid-20s; in Japan in 1949, a single woman that old is approaching the end of her shelf life. His sister warns the professor that after his death Noriko will be left alone in the world; it is his duty to push her out of the nest and find a husband who can support her. The professor reluctantly agrees. When his daughter opposes any idea of marriage, he tells her he is also going to remarry. That is a lie, but he will sacrifice his own comfort for his daughter’s future. She marries.

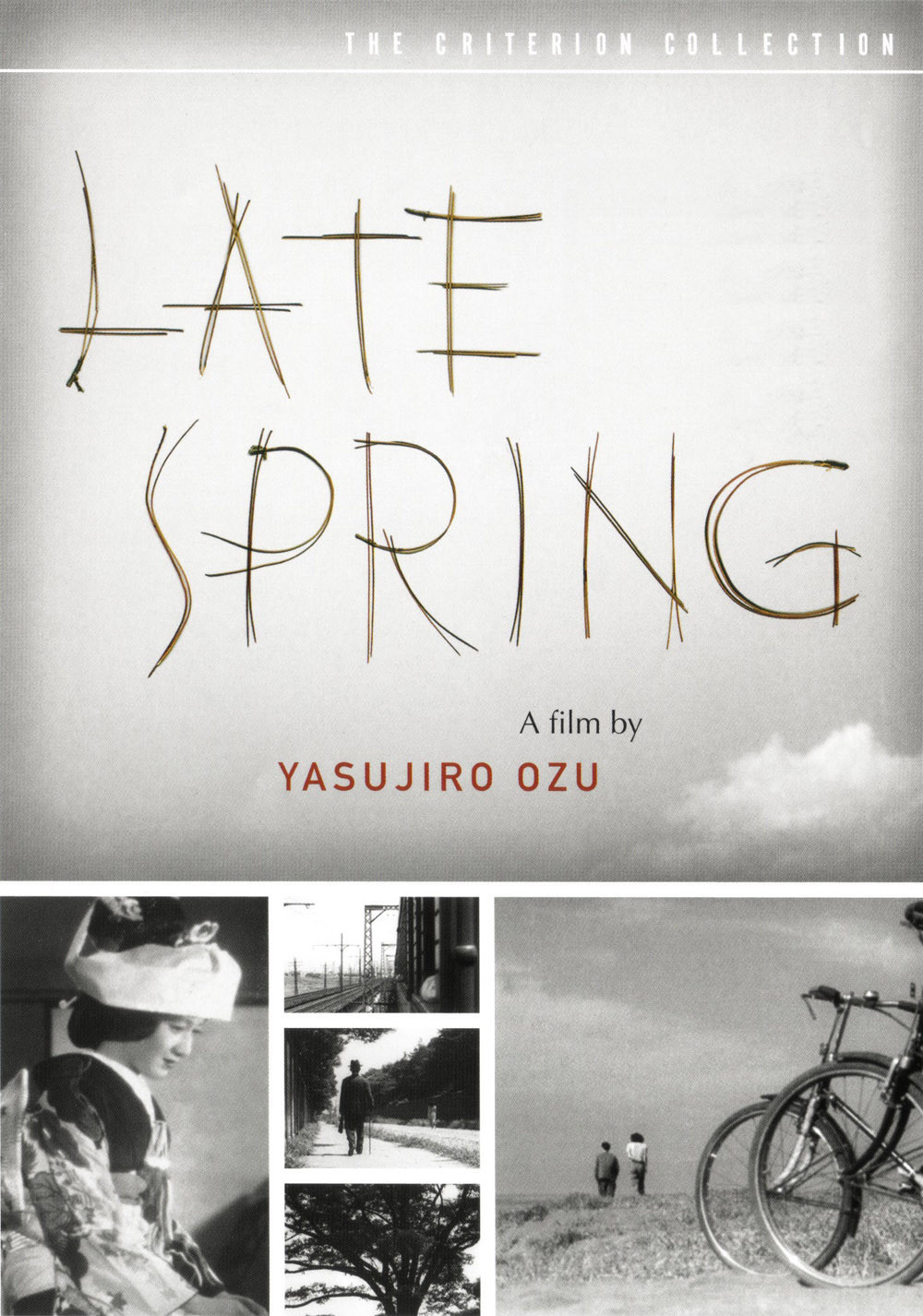

And that, essentially, is what happens on the surface in Yasujiro Ozu’s “Late Spring” (1949). What happens at deeper levels is angry, passionate and — wrong, we feel, because the father and the daughter are forced to do something neither one of them wants to do, and the result will be resentment and unhappiness. Only the aunt will emerge satisfied, and Noriko’s husband, perhaps, although we never see him. “He looks like Gary Cooper, around the mouth, but not the top part,” the aunt tells her.

It is typical of Ozu that he never shows us the man Noriko will marry. In his next film, “Early Summer” (1951), the would-be bride in an arranged marriage sees the groom only in a golfing photo that obscures his face. Ozu is not telling traditional romantic stories. He is intently watching families where the status quo is threatened by an outsider; what matters to the brides is not what they are beginning but what they are ending.

The women in both films are named Noriko, and they are both played by Setsuko Hara, a great star who would drop everything to work with Ozu. When the studio asked Ozu to consider a different actress for the second film, he refused to make it without Hara.

In “Early Summer,” Noriko lives with her brother, his family, and their aged parents. She has no desire to marry — at least, not the golfer. The same actor, Chishu Ryu (1904-1993) plays the professor in the first film and the brother in the second; in Ozu’s “Tokyo Story” (1953), he plays the grandfather and Hara is his daughter-in-law. In all three films he looks the correct age for his character; how he did that so convincingly between the ages of 45 and 49 is beyond my ability to explain.

“Late Spring” began a cycle of Ozu films about families; the seasons in the title refer to the times in the lives of the characters, as in his final film, “An Autumn Afternoon” (1962). Did he make the same film again and again? Not at all. “Late Spring” and “Early Summer” are startlingly different. In the second, Noriko takes advantage of a conversational opening to overturn the entire plot; to avoid marrying the golfer, she accepts a man she has known for a long time — a widower with a child, whose mother’s dearest wish is that her son marry Noriko. The man goes along with his mother’s plan, indeed is pleased once he absorbs it; the meddling woman in this case has made two people happier.

“Late Spring” tells a story that becomes sadder the more you think about it. There is a tension in the film between Noriko’s smile and her feelings. Her smile is often a mask. She smiles brightly during a strange early scene where she talks with a family friend, Onodera, who has remarried after the death of his wife. Such a second marriage is “filthy and foul,” she says, and it disgusts her. She smiles, he laughs. Yet she is very serious.

Onodera tells the professor it’s his duty to marry off Noriko, and suggests an excellent prospect: Hattori, the professor’s assistant. Noriko and Hattori take a bicycle trip to the beach, and later have dinner; we think perhaps such a match will work. But when Shukichi suggests it to his daughter, she laughs and tells him Hattori is already engaged. How and when she learned that is left offscreen; what we do see is Hattori inviting her to a concert, her telling him she doesn’t want to make “trouble,” and Hattori at the concert with his hat on an empty seat. There is the possibility that Noriko could have married Hattori after all; she likes him, he likes her, he might leave his fiancee; the concert invitation is crucial, but she will not leave her father. This is her sacrifice, to match his later in the film.

Now Masa (Haruko Sugimura), her aunt, comes up with a new candidate, the Gary Cooper look-alike named Satake. Noriko tells her friend, “I think he looks more like the local electrician.” Realizing that Noriko will not willingly leave her father, Masa proposes to the professor that he marry a younger widow, Mrs. Miwa. The professor is as happy as his daughter to remain single, but understands Masa’s scheme to deceive Noriko.

Ozu brings everything to a head during an extraordinary scene at a Noh performance, where Noriko sits next to her father. The professor nods across the room to Mrs. Miwa, who smiles and nods back. Noriko observes this and loses all interest in the play; her head bows in sadness, and afterward she tells her father, “I have to go away somewhere,” and all but flees from his side.

There’s a later scene of uncomfortable confrontation. “Will you marry?” Noriko asks him. “Um,” he says, with the slightest nod. She asks him three or four different ways. “Um.” Finally, “that woman we saw today?” “Um.” He defends arranged marriages: “Your mother wasn’t happy at first. I found her weeping in the kitchen many times.” Not the best argument for a father trying to convince his daughter to marry.

Masa the aunt, having proposed the new groom, now acts as if it is a settled thing, and begins to plan the approaching marriage. Noriko goes along, smiling as always. We see her beautiful but sad in her traditional wedding dress, but we do not see her wedding or meet her husband. Instead, we come home alone with the professor, who admits his own marriage plans were “the biggest lie I ever told.” In one of the saddest scenes ever filmed by Ozu, he sits alone in his room and begins to peel an apple. The peel grows longer and longer until his hand stops and it falls to the floor and he bows his head in grief.

The professor’s decision is often described as his “sacrifice” of her. And so it is, but not one he wants to make. Nor does she want to leave. “I love helping you,” she says, “Marriage wouldn’t make me any happier. You can remarry, but I want to be at your side.” There is an academic paper exploring the possibility of repressed incest in “Late Spring,” but I doubt that occurred to Ozu; Noriko has a hidden well of disgust about sex, I believe, which is revealed in her strong feelings about remarriage — once is bad enough. She wants to stay safe in her home with her father, forever.

“Late Spring” is one of the best two or three films Ozu ever made, with “Early Summer” deserving comparison. Both films use his distinctive later visual style, which includes precise compositions for a camera that almost never moves, a point of view often representing the eye-level of a person sitting on a tatami mat, and punctuation through cutaways to unrelated exteriors. He almost always used only one lens, a 50mm, which he said was the closest to the human eye.

Here he wordlessly uses time and space to establish the routine and serenity of the household arrangements between father and daughter, in a sequence showing them coming and going, upstairs and down, through the rooms and central corridors of their house. They know their way around each other. Late in the film, threatened by the marriage, Noriko keeps picking things up and putting them on a table, compulsively acting out her domestic happiness.

So much happens out of sight in the film, implied but not shown. Noriko smiles but is not happy. Her father passively accepts what he hates is happening. The aunt is complacent, implacable, maddening. She gets her way. It is universally believed, just as in a Jane Austen novel, that a woman of a certain age is in want of a husband. “Late Spring” is a film about two people who desperately do not believe this, and about how they are undone by their tact, their concern for each other, and their need to make others comfortable by seeming to agree with them.

The Ozu retrospective continues at the Gene Siskel Film Center, 164 N. State. “Early Summer” plays at 5 p.m. Saturday and 6 p.m. Feb. 23. Ebert’s reviews of “Tokyo Story” and “Floating Weeds” are in the Great Movies section.