“There’s your dog; your dog’s dead. But where’s the thing that made it move? It had to be something, didn’t it?”

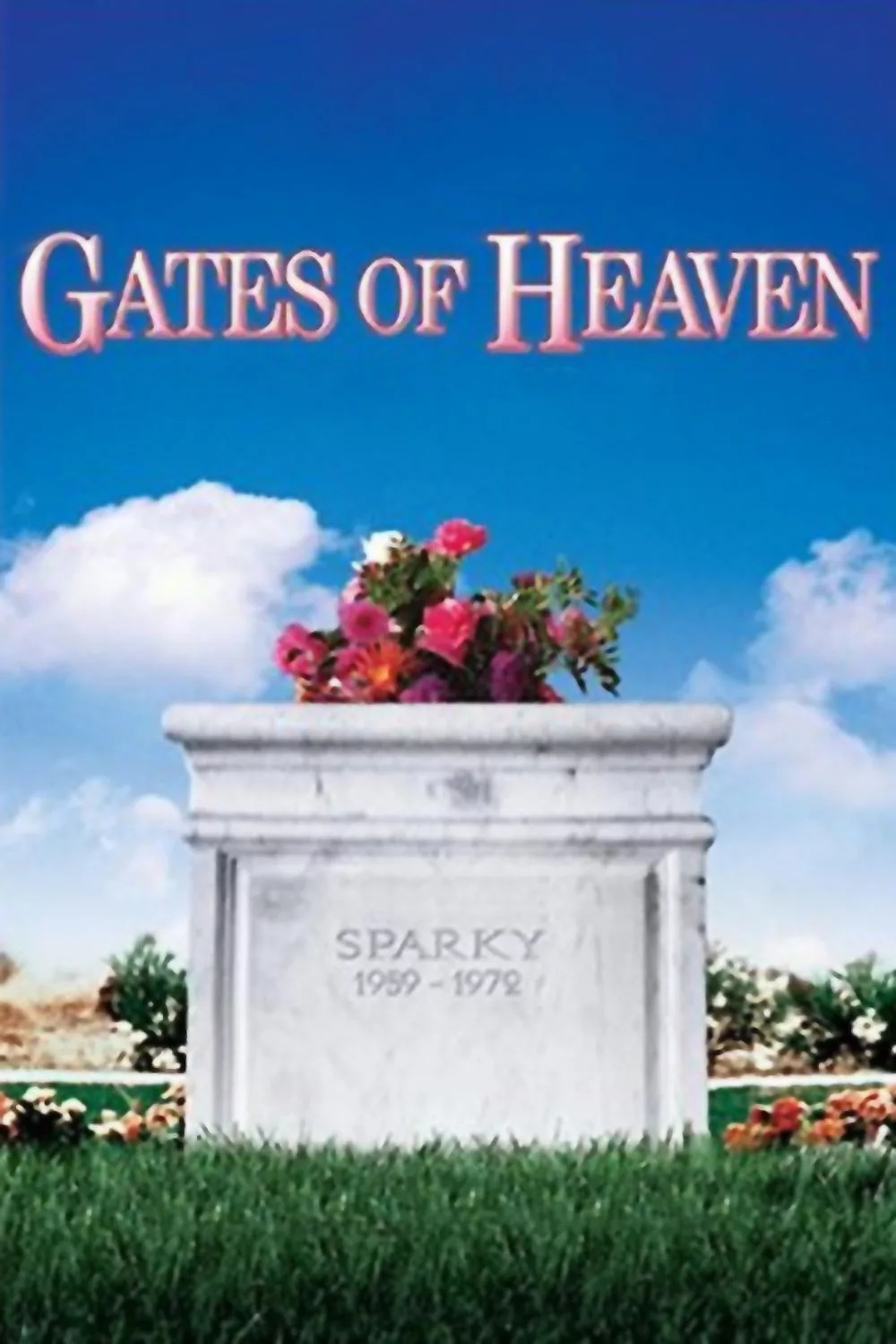

These words, by a woman who has just buried her dog, are spoken in “Gates of Heaven.” They express the central mystery of life. No philosopher has stated it better. They form the truth at the center of Errol Morris’ 1978 documentary, which is surrounded by layer upon layer of comedy, pathos, irony, and human nature. I have seen this film perhaps 30 times, and am still not anywhere near the bottom of it: All I know is, it’s about a lot more than pet cemeteries.

In the mid-1970s, Morris, who had never made a film, read newspaper articles about the financial collapse of the Foothill Pet Cemetery in Los Altos, Calif. After much legal unpleasantness, dead animals were dug up and relocated in the Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park, in the Napa Valley. Thinking there might be a film in these events, Morris went with cinematographer Ned Burgess to interview Floyd McClure, the paraplegic operator of the first cemetery, and the Calvin Harberts family, of Bubbling Well.

The film they made has become an underground legend, a litmus test for audiences, who cannot decide if it is serious or satirical, funny or sad, sympathetic or mocking. Morris went on to become one of America’s best-known documentarians, with such credits as “The Thin Blue Line,” “A Brief History of Time” and his new release “Fast, Cheap and Out of Control.” But “Gates of Heaven” remains in a category by itself, unclassifiable, provocative, tantalizing. When I put it on my list of the 10 greatest films ever made, I was not joking; this 85-minute film about pet cemeteries has given me more to think about over the past 20 years than most of the other films I’ve seen.

The film is told without narration, by the people involved. It falls into two parts, separated by a remarkable monologue. The first half belongs to Floyd McClure, who recalls his “Kismet idea” of locating a pet cemetery on a site that had “great visual ability.” He remembers with ferocity a childhood experience when he helped a friend bury a pet before the garbage trucks could haul it away, and his bottom teeth are bared in anger as he talks about his great enemy, rendering plants. When he first visited one, as a 4-H kid, he recalls thinking, “I’m sitting on the floors of hell right now.”

His words, and the words of everyone in the film, are heard with great intensity: They express themselves in an American idiom that approaches poetry, and even their mistakes are eloquent, as when McClure talks about performing “pacific tasks.” But Morris also has an ear for irony, and we suspect his wicked grin behind the camera as McClure expands on the problem of living near a rendering plant: “The only thing that hit your nostrils wasn’t that good piece of meat you bought to eat … you first had to grab the wine glass off the table, and take a whiff of that, to get the smell of the rendering company out of your nose before you could eat.”

His scenes are intercut with the sad recollections of some of his investors, in particular a man who apologetically says he lost $30,000 on the scheme, and then sighs in a way that lets you know he will never see that much money again. And there is comic relief in the form of the arch-enemy, the owner of a rendering plant, who reports that people just don’t want to know what happens to dead animals: “Every once in a while they’ll lose a giraffe at the zoo, or they’ll lose Big Bertha, or Joe the Bear …” And to avoid offending the sensibilities of animal lovers, “we actually have to deny we have that animal.”

The centerpiece of the film is an extended monologue spoken by a woman named Florence Rasmussen, who sits in the doorway of her home, overlooking the first pet cemetery. William Faulkner or Mark Twain would have wept with joy to have created such words as fall from her mouth, as she tells the camera the story of her life: She paints the details in quick, vivid sketches, and then contradicts every single thing she says.

Then the film journeys to the Napa Valley, where the Cal Harberts family operates the Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park. He’s also founded a church that teaches that God loves animals as well as men. Much of his bombast is undercut by his tart-tongued wife, Scottie, but she best expresses the church’s philosophy: “Surely at the gates of heaven an all-compassionate God is not going to say, well, you’re walking in on two legs–you can go in. You’re walking in on four legs–we can’t take you.”

We meet the Harberts’ two sons. Danny is a sad romantic with a wispy mustache, who started out well in college, but then started partying all night. He lost his girlfriend, and now knows, “a broken heart is something that everyone should experience.” His older brother, Philip, sold insurance in Salt Lake City but has now returned to Napa, where he analyzes his tasks (digging graves, combing dead dogs) in terms of the success principles of W. Clement Stone. Danny is more pragmatic, analyzing the challenge of digging a grave: “You don’t want to make it too large because you don’t want to waste space, and you don’t want to make it too small because you can’t get the thing in there.”

In one remarkable unbroken shot, a grieving pet owner delivers a long speech about the death of her dog and the measures she recommends to other pet owners, and when she gets to the very last word, her husband interrupts to pronounce it with bleak finality: “Neutered.” This is the kind of perfect moment that cannot be written and cannot be anticipated; it can only be filmed as it happens.

There is an undertone to the Harberts family that is hard to put a finger on. The parents seem prosperous and live in a comfortable home, but Danny is being gnawed by loneliness, and Philip, having “relocated his little family,” has undergone severe retrenchment. In the insurance game, he says, “I went from a salesMAN to a sales MANager” (he likes plays on words), and would impress employees by arranging his office “to display the maximum trophies.” But now he admits to “real fear” as he attempts to memorize the routes he must drive to pick up dead animals from veterinarian offices.

Danny’s life is poignant, too. After getting his degree in business, he didn’t find a job, and returned home to live in a cabin where he grows marijuana on the windowsill and lays down tracks on his sound system. In the afternoons, when the guests have gone, he places his 100-watt speakers on a hilltop and plays his guitar, which can be heard “all over the valley.” He is like the last of a species, repeating a mournful call for another of his own kind.

The signs on the pet markers are eloquent in their way. “I knew love; I knew this dog.” “Dog is God spelled backwards.” “For saving my life.” At the end of the film, having laughed earlier, we find ourselves silent. These animal lovers are expressing the deepest of human needs, for love and companionship.

“When I turn my back,” says Floyd McClure, “I don’t know you, not truly. But I can turn my back on my little dog, and I know that he’s not going to jump on me or bite me; but human beings can’t be that way.”

When I am asked to lecture and show a film, I often bring “Gates of Heaven.” Afterward, the discussions invariably rage without end: Is he making fun of those people? Are people ridiculous for caring so much about animals? The film is a put-on, right? It can’t really be true?

Cal Harberts promises in the film that his park will still be in existence in 30, 50 or 100 years. Twenty years have passed. I searched for the Bubbling Well Pet Memorial Park on the World Wide Web, and found it (www.bubbling-well.com). There is information about its “Garden of Companionship,” “Kitty Curve,” and “Pre-Need Plans,” but no mention of this film. Or of the Harberts.