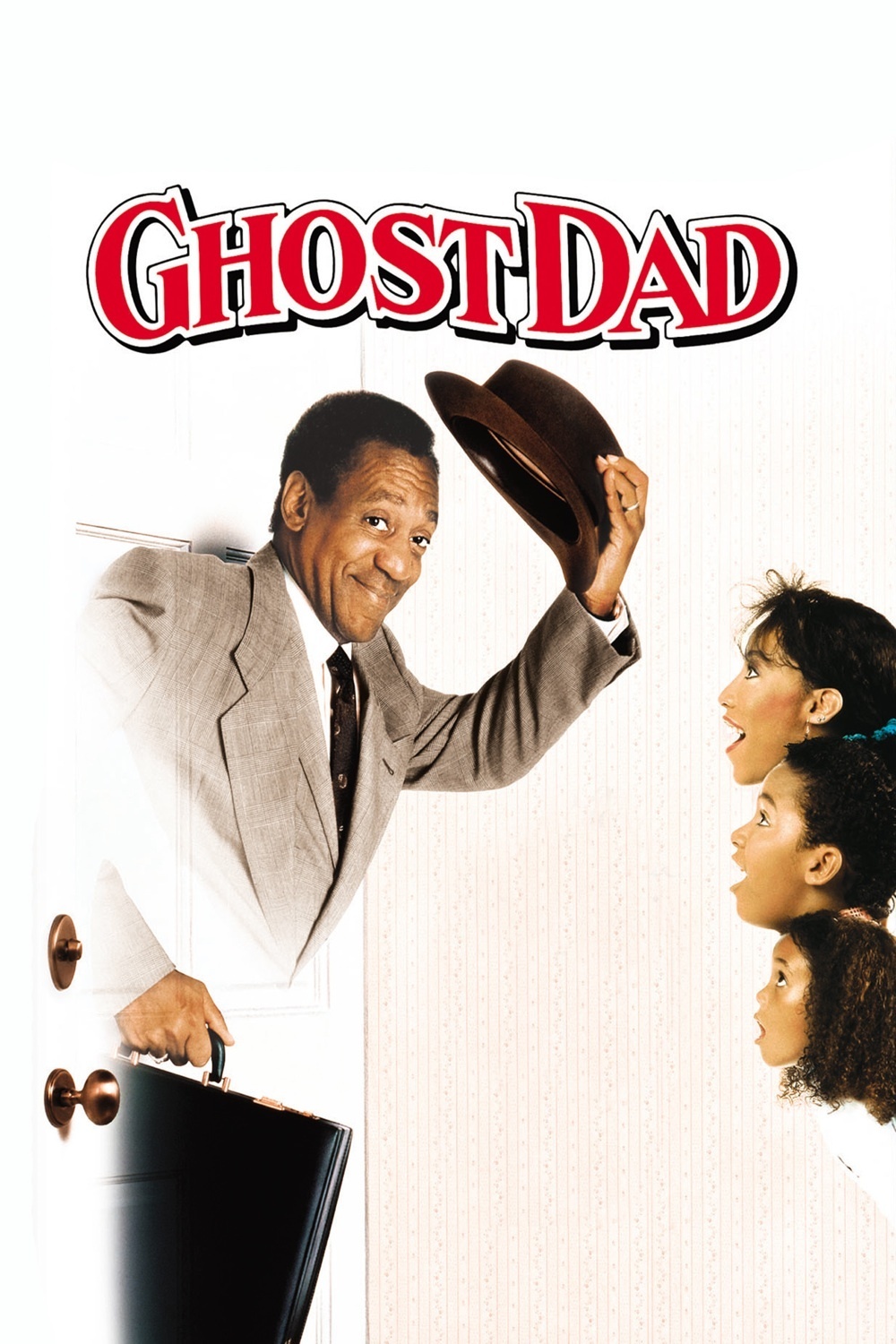

“Ghost Dad” is a desperately unfunny film – a strained, contrived construction that left me shaking my head in amazement. How does Bill Cosby, so capable on television, get himself into movie disaster zones like this movie and his previous one, “Leonard Part 6”? How could Sidney Poitier, a skilled filmmaker with an actor’s sense of timing, have been the director of this mess? How did a production executive go for it? Who ever thought this was a good idea? The story begins with Cosby as a widower with three children – two smaller ones, and Diane (Kimberly Russell), a teenager who helps look after them. He’s a busy executive who hopes to close a big deal on Thursday that will mean a raise, life insurance, a pension plan, a new car, and I forget what else. But before Thursday comes, Cosby takes a fatal cab ride and becomes a ghost.

Most movie ghosts are defined and restrained by certain ground rules. What kind of ghost is Cosby? The kind of ghost his children can see and hear sometimes, but not at other times, and who can sometimes pick up stuff although at other times his hands go right through things, and who is invisible in bright lights but visible in darkened rooms. In other words, a ghost created under such confusing rules that it can be anything at any time, which means that sometimes in the same scene or even the same series of shots Cosby appears or disappears according to no logical pattern.

But we’re getting ahead of the story. What about that cab ride? The driver is some kind of wigged-out freak who thinks Cosby is God or the devil, and who drives at high speeds down city streets and country roads, sometimes getting from the city to the country in one shot, as if you could turn a downtown city corner and be instantly on a bridge in the wilderness. When the taxi is teetering on top of the bridge, not even the weight of Cosby’s body hanging from an open door can pull it over the edge, but a few seconds later all it takes is a slight shift by the cabbie to send the taxi tumbling to a watery grave.

Why do I describe silly details like this? Because they illustrate how half-baked and lame-brained the screenplay is. The movie doesn’t exhibit the slightest attempt to be consistent, logical or sensible in anything, and there are scenes so pointless and unmotivated that attentive audiences will ask what they’re doing in the movie.

Consider, for example, a scene where Cosby’s boss and the entire executive committee turn up at his house demanding action on the big deal. Cosby (invisible) tells his young son to take them into the library and “stall them,” and then he wraps himself in mufflers to make himself visible (like the hero of “The Invisible Man”), so that he can go next door and have a meaningless conversation with his neighbor. Why go next door when his whole career hangs in the balance? The movie doesn’t even begin to explain, and during his visit to the neighbor I paid close attention without being able to figure out what he was trying to say to her, or why he was there in the first place.

There are many other equally inane scenes, of which the climactic confrontation in the hospital emergency room may set some kind of record for idiocy. Both the father and Diane are now ghosts.

And although Diane has been established as a person who is serious about her responsibilities to her young sibling, she now finds she likes being a ghost, and her dad has to deliver a bittersweet dirge about the beauty of life before she utters the immortal line, “I’ll go back to my body if you’ll go back to yours.” Bill Cosby is not one of the great actors of our time, but on TV he delivers a serviceable performance week after week, and can rise to a dramatic occasion. That’s why his performance in this movie is so surprising. He overacts in the most unconvincing way, allowing his face to mime every thought and emotion. He blubbers and pleads and complains at an intensity that’s way over the top, so that the more restrained work by the other actors seems like a form of criticism. Is he such a star that his performances are considered above criticism? Was there nobody on the set – not even Poitier – to help him find the right note?