Charles Bronson is usually at the silent center of action movies. He says little, but his muscles are coiled and his eyes are alert, and sooner or later, he will unleash violence. That’s why it’s interesting and even a little unsettling to find him in a whimsical Western romance. We don’t expect Bronson to make small talk, to be charming, to sweep a pretty woman off her feet – but that’s what he does in “From Noon to Three.” And he does it with a certain rugged grace.

The movie opens unsteadily and takes too long to close, but the things that happen between noon and three give us new ideas about Bronson’s possibilities. I’ve always thought of him as a superb physical actor with a limited emotional range; here he finds his way very easily through a romance by Frank D. Gilroy, who wrote and directed the movie and whose best-known work is “The Subject Was Roses.”

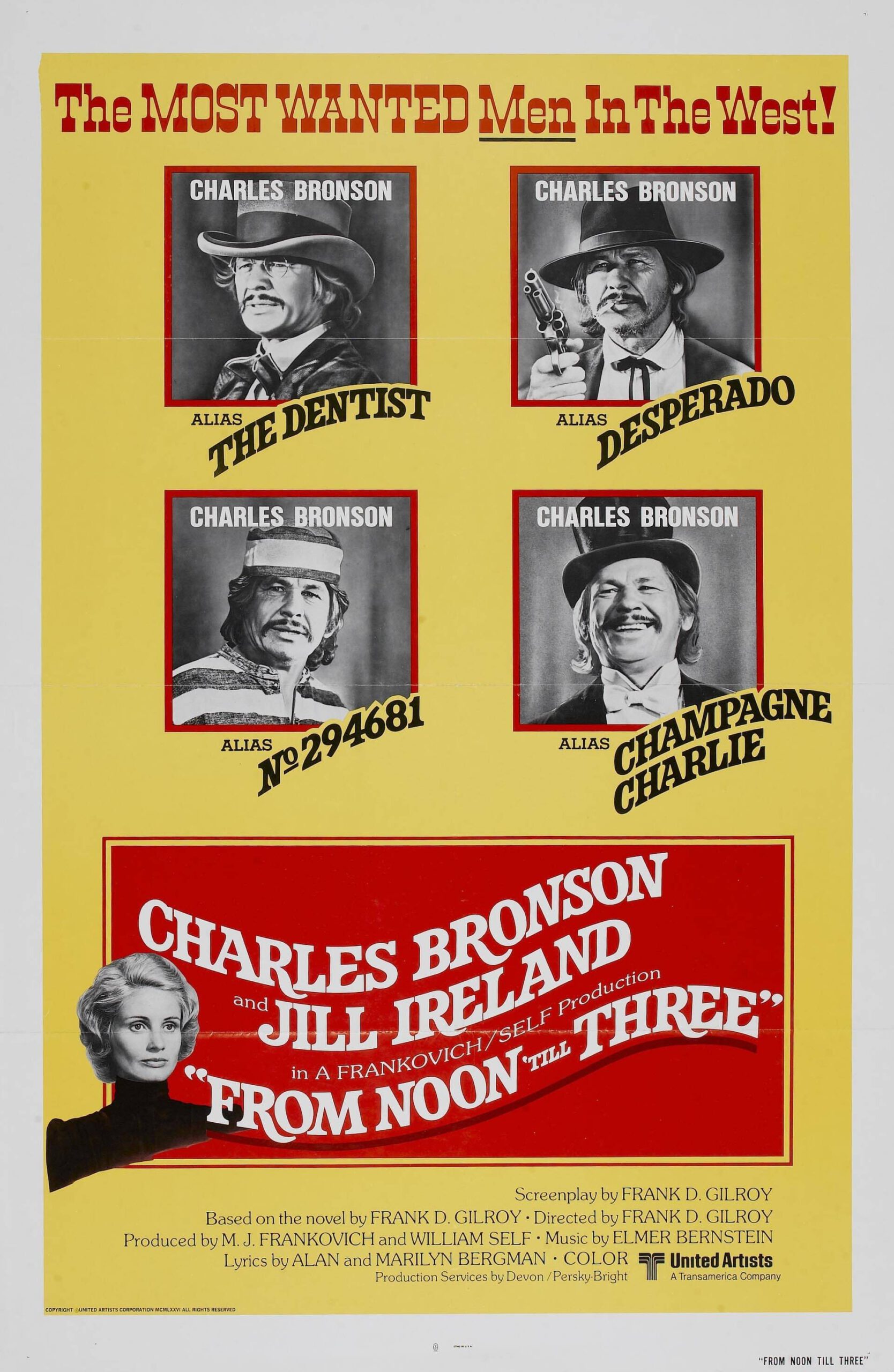

Bronson plays a desperado named Graham Dorsey, who stops off at a ranch house on his way to hold up a bank, and falls in love with the beautiful widow who lives there. The widow is played by Bronson’s wife, Jill Ireland (this is their 11th film together) and she’s aloof and skittish as the sophisticated lady from the East. But Graham Dorsey works on her. He kids her and woos her, lies to her and seduces her; finally she pulls the covers off the fancy furniture her late husband brought from the East and decides there’s been enough mourning in her house.

“These scenes between Bronson and Ireland are what make the movie worth seeing. Bronson is courtly and calculating, Ireland is reserved (and yet wants to be courted by this strange, determined man) and the two of them generate a real sexual presence. If Bronson cannot easily play a character totally unlike himself, he can certainly project strongly within his own range. His movies seldom give him the opportunity to play love scenes (most of the actresses in them – Miss Ireland included – are backdrops for the action.) In “From Noon to Three,” it’s as if a capacity for humor and gentleness has been released. The movie’s problems are in the framework around the long central passages. Gilroy adds a layer of irony and legend that isn’t really necessary – we’d rather see more of the widow and the desperado. After Dorsey is captured and sent to prison, the widow writes a best-selling book about her romantic afternoon. The couple becomes the stuff of legend, the subject of popular songs and Broadway reviews and, when Dorsey comes back after several years to reclaim his love, she’d . . . well, she’d rather be a legend than his lover.

This unhappy development drives Graham Dorsey to despair. He’s surrounded on all sides by images of his great love affair – by souvenir picture albums, guided tours of the widow’s house and cheap editions of her bestseller. But he can neither recapture their love affair or even convince people he IS Graham Dorsey. And so he wanders from one tragic adventure to the next, while the movie takes far too long to end. The epilog seemed unnecessary to me; the relationship between the bank robber and the sophisticated lady was enough for an intriguing film. I wish Gilroy had explored it further, instead of allowing it to get lost in ironies that go on forever.