“Farewell My Concubine” is two films at once: An epic spanning a half-century of modern Chinese history, and a melodrama about life backstage at the famed Peking Opera. The idea of viewing modern China through the eyes of two of the opera’s stars would not, at first, seem logical: How could the birth pangs of a developing nation have much in common with the death pangs of an ancient and ritualistic art form? And yet the film flows with such urgency that all its connections seem logical. And it is filmed with such visual splendor that possible objections are swept aside.

The film opens on a setting worthy of Dickens, as two young orphan boys are inducted into the Peking Opera’s harsh, perfectionist training academy. The physical and mental hardships are barely endurable, but they produce, after years, classical performers who are exquisitely trained for their roles.

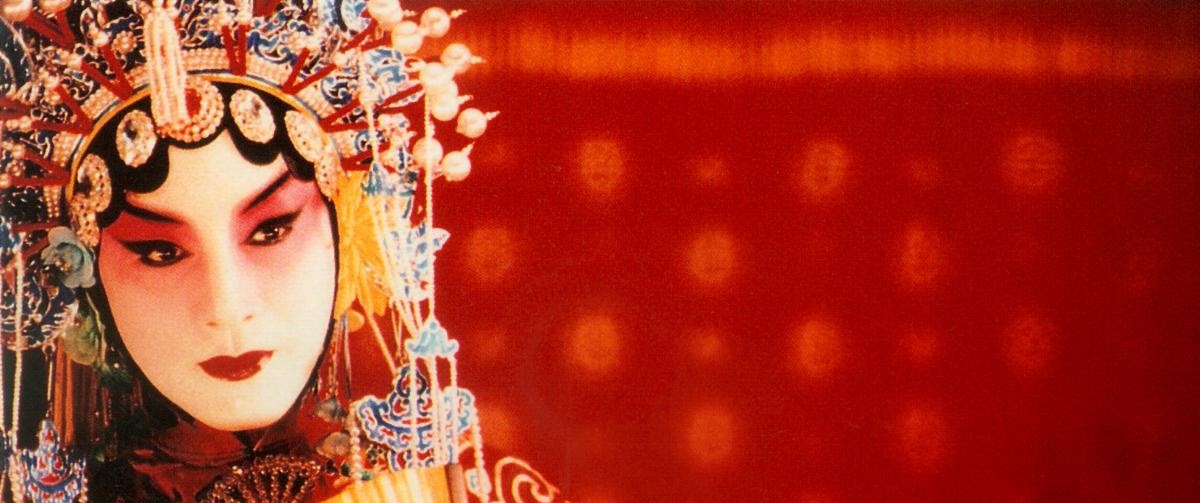

We meet the delicate young Douzi (Leslie Cheung), who is assigned to the transvestite role of the concubine in a famous traditional opera, and the more masculine Shitou (Zhang Fengyi), who will play the king. Throughout their lives they will be locked into these roles onstage, while their personal relationship somehow survives the upheavals of World War II, the communist takeover of China and the Cultural Revolution.

Under the stage names of Cheng Dieyi (Leslie Cheung) and Duan Xiaolou (Zhang Fengyi), the two actors become wildly popular with Peking audiences. But they are politically unsophisticated, and Dieyi in particular makes unwise decisions during the Japanese occupation, leading to later charges of collaborating with the enemy.

Their personal relationship is equally unsettled. Dieyi, a homosexual, feels great love for Xiaolou, but the “king” doesn’t share his feelings, and eventually marries the beautiful prostitute Juxian, played by China’s leading actress, Gong Li. Dieyi is resentful and jealous, but during long years of hard times Juxian stands heroically by both men.

That the Peking Opera survives at all during five decades of upheaval is rather astonishing; apparently its royalist and bourgeois origins are balanced against its long history as a Chinese cultural tradition, so that even the Red Chinese accept it in all of its anachronistic glory. What almost does it in, however, is the Cultural Revolution, as shrill young ideogogues impose their instant brand of political correctness on the older generations, and characters are forced to denounce one another. Xiaolou even denounces Dieyi as a homosexual, and Dieyi counterattacks by denouncing his friend’s wife as a prostitute.

The movie’s director is Chen Keige, who knows about the Cultural Revolution first hand. Born in 1952, he was sent in 1969 to a rural area to do manual labor; the scenes involving the Peking Opera’s youth training programs may owe something to this experience.

The son of a filmmaker, he was a Red Guard and a soldier before enrolling in film school, and at one point actually denounced his own father, an act for which he still feels great shame. (The father, sentenced to hard labor for several years, worked with his son as artistic director of this film.) “Farewell My Concubine” won the Grand Prix at Cannes this year, but Chen Keige returned to find his film first shown, then banned, then shown again and banned again in China. His particular offense was to show a suicide taking place in 1977, a year in which, government orthodoxy holds, life in China did not justify such measures. The Chinese authorities were also uneasy about the homosexual aspects in the story.

What is amazing, given the conditions under which the film was made, is the freedom and energy with which it plays. The story is almost unbelievably ambitious, using no less than the entire modern history of China as its backdrop, as the private lives of the characters reflect their changing fortunes: The toast of the nation at one point, they are homeless outcasts at another, and nearly destroyed by their political naivete more than once. (It is perhaps an unfair quibble that although they must be 60ish by the end of the story, they look only somewhat older than when they were young men.) The Peking Opera itself is filmed in lavish detail; the costumes benefit from the rich colors of the world’s last surviving three-strip Technicolor lab, in Shanghai, and the backstage intrigues and romances are worthy of a soap opera. In a season when “M. Butterfly” sank under the weight of John Lone’s uncompelling performance as a transvestite, Leslie Cheung’s concubine is never less than convincing, and his private life – he is essentially raised by the opera as a homosexual whether or not he consents – contains labyrinthine emotional currents. Gong Li, as the prostitute, is sometimes glamorous, sometimes haggard, and always at the mercy of two men whose work together has defined their individual personalities.

The epic is a threatened art form at the movies. Audiences seem to prefer less ambitious, more simple-minded stories, in which the heroes control events, instead of being buffeted by them.

“Farewell My Concubine” is a demonstration of how a great epic can function. I was generally familiar with the important moments in modern Chinese history, but this film helped me to feel and imagine what it was like to live in the country during those times. Like such dissimilar films as “Dr. Zhivago” and “A Passage to India,” it took me to another place and time, and made it emotionally comprehensible. This is one of the year’s best films.