When the results of the once-a-decade British Film Institute poll of world film experts about history’s best films were announced in 2012, the change that attracted the most notice was at the top of the list. Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo,” which back in the day was considered a mere commercial entertainment like many another, jumped to the number one spot, displacing Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane,” which had occupied it for a half-century and seemed like it might forever. But the change that startled this voter the most came a bit further down, where Dziga Vertov’s “Man with a Movie Camera” knocked Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” out of the top ten altogether.

While many factors may have contributed to these and other changes in the latest poll, it was hard to escape the impression that an important one was the decline in the teaching of film history, something that many of us who’ve taught cinema studies at universities have observed. In 2012, for the first time, the BFI included in its poll not just critics but also programmers, curators and others whose understandings no doubt have been shaped by the academic de-emphasis on film history in favor of the kind of topical trendiness that may see the cheeky “experimentalism” of “Man with a Movie Camera” as more crucial than the symphonic grandeur of “Potemkin.”

Defenders of these latter-day decisions might well say that tastes change from decade to decade. Which they do. But if supposed film experts no longer have a firm grasp of Eisenstein’s importance, what of ordinary filmgoers, even cinephiles? That was the question, surely, faced by Peter Greenaway when he set out to make a film about the Russian director’s journey to Mexico in 1930 to make the ill-fated, never completed “Que Viva Mexico!” And it was perhaps crucial in Greenaway’s decision to downplay or ignore various of this potentially fascinating subject’s intellectual, cultural, political, artistic and psychological aspects in order to propose that the really important thing about Eisenstein’s trip was the chance it gave him to lose his virginity as a gay man at the age of 33.

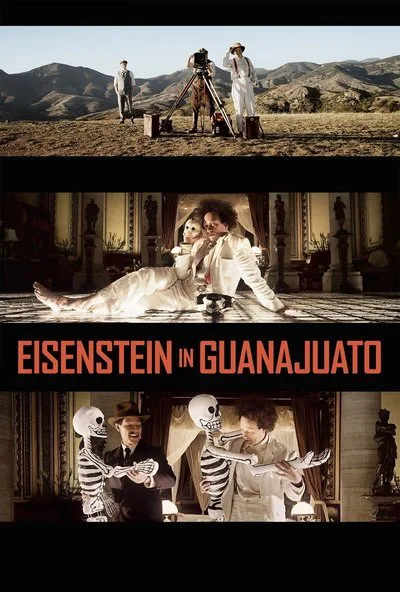

Greenaway, the British painter turned filmmaker who turned out a number of impressive experimental films before springing on the art-film world with the witty provocations of early features including “The Draughtsman’s Contract” and “The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover,” hasn’t made a really good film in a quarter-century, so the disappointments of “Eisenstein in Guanajuato” come as no surprise. Neither does the sense that Greenaway, still trapped in that cultural moment when “post-modern” meant unwavering whimsicality, unfortunately can’t muster a degree of seriousness even when the subject cries out for it. He’s now like Ken Russell on laughing gas, and his latest indeed comes off as “The Music Lovers” replayed not as tragedy but as farce.

When the film begins, with Eisenstein (played by Finnish actor Elmer Bäck, who has a very un-Russian propensity for trilled r’s) and entourage sweeping into Guanajuato like a diva into an opera house, Greenaway gives us clips of the three films that established the Russian’s worldwide renown: “Strike!,” “Potemkin” and “October.” But the mention of these masterworks comes off as little more than name-dropping, as do the appearances of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, who vanish as soon as they welcome the grinning, frizzy-haired, white-suited maestro to Mexico. Afterwards, Sergei ascends to his sumptuous hotel room (the movie’s primary set), where he strips naked, grins some more and begins talking to his penis, which is looking a bit more robust due to the proximity of Eisenstein’s newly appointed guide, Palomino Cañedo (Luis Alberti), a handsome professor of comparative religion.

Greenaway is known for the nudity, piss, shit, vomit, spit and other excretions deployed in his films, but here those mannerisms come across almost as tics arrayed decoratively around the central question: How long will it be before Greenaway gets the Russian and the Mexican into bed? It takes almost an hour, and the result is an unstinting sex scene in which Palomino (yes, there are plenty of equine jokes) mounts Sergei from behind and delivers him into ecstasy, after which he plants a small red flag between his butt cheeks.

The question of whether any such thing actually happened is, of course, a trifling one. In interviews, Greenaway often throws up a smokescreen of hyper-intellectual verbiage around the most crucial assertions of his films, and this one is no different. How does he know Eisenstein first had sex with a man in Mexico rather than, say, the gay demimonde of Berlin? He offers no proof. And what evidence does he have of an affair with Señor Cañedo? Eisenstein’s erotic drawings (which contain plenty of heterosexual images too) and his films’ iconography suggest he may have been attracted primarily to hunky young working men. Leave it to Greenaway to make the object of Sergei’s lust a professor of comparative religion!

But the question of accuracy pales beside the whole conceit’s essential triteness. Undoubtedly, Eisenstein was smitten with the pure sensuality of Mexico, the bright light, striking colors, luxuriant foliage and exotic animals. He was also was taken with the way that death is celebrated in Mexican culture and an event like the Day of the Dead. All of this, according to his own testimony, had a liberating impact on him creatively, both on his drawing and his filmmaking. But Greenaway, in reducing that breakthrough to a single, silly roll in the hay, falls back on the stalest of clichés. We get very little sense of Mexico or of Eisenstein’s creative growth during the lengthy, doomed shooting of “Que Viva Mexico!”

Two final notes. First, Greenaway sorely misses the collaboration of composer Michael Nyman, whose propulsive music so enhanced his early features. Second, “Eisenstein in Guanajuato” features some of the worst post-synching seen in any recent movie. If Eisenstein, the consummate craftsman, would have regretted Greenaway’s penchant for pointless and overdone circular tracking shots, he surely would have groaned at how the actors’ lips here and the words they speak are so often on different timetables.

Note: “Eisenstein in Guanajuato” will be playing at the Siskel Film Center in Chicago starting February 19th.