I don’t subscribe to the theory that adaptations of artistically successful source material need remain overly faithful. An adaptation, at its best, should also be an interpretation. It should offer a personal take, a new angle, deepening certain themes while naturally reducing others, etc. However, the decisions made when radically altering source material should feel purposeful, not arbitrary and random. It’s not so much when our favorite books are adapted differently that makes fans angry but when they are lessened by the differences. Such is the case with Adam Wingard’s depressingly awful “Death Note,” premiering today on Netflix. Several of the changes to Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata’s brilliant manga have already been widely reported, including the whitewashing of the entire project by relocating it from Japan to Seattle, but those are just the symptoms of a greater disease known as complete creative bankruptcy.

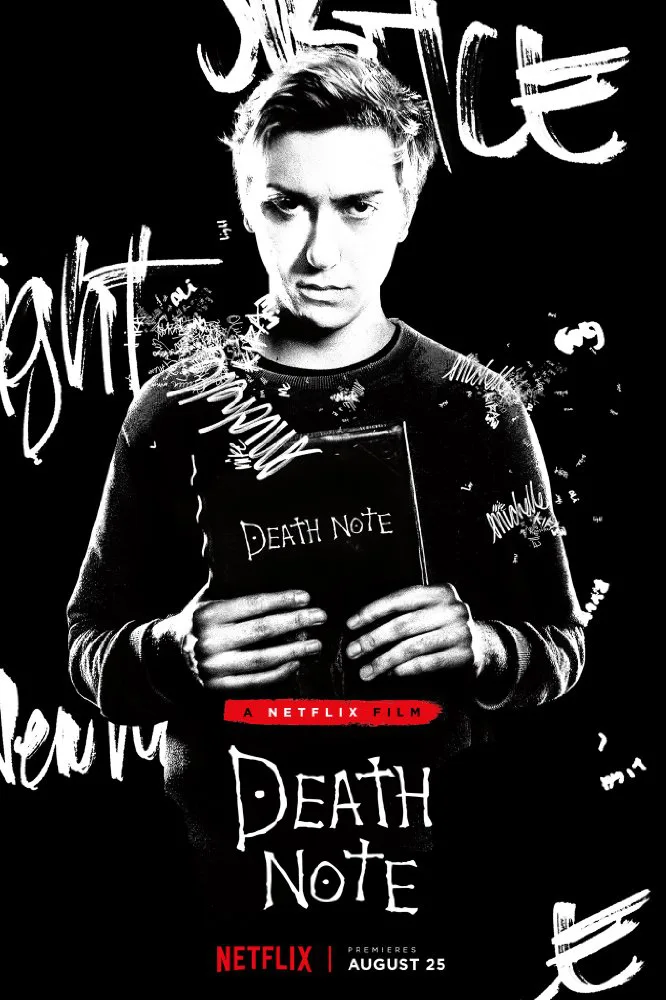

The concept of “Death Note,” the manga and at least start of the film, is simple. A boy named Light Turner (Nat Wolff) finds a book dropped to Earth by a Shinigami, a Japanese death demon somewhat akin to the Grim Reaper, named Ryuk, voiced in the film by Willem Dafoe. The book says Death Note on the cover and has names written in it over centuries. It also has the rules. Write someone’s name in the book and they will die. In the manga, the rules are extensive and repeated often, but Wingard and writers Charley Parlapanides & Vlas Parlapanides and Jeremy Slater understandably simplify things a bit. In the movie, Light writes a name and a manner of death and it unfolds in front of his eyes. That’s about all you need to know. What would you do with that kind of power?

In the manga, Light begins testing his own morality by killing criminals, allowing them to die peacefully of heart attacks as he tests the boundaries of playing God. Perhaps recognizing this wouldn’t be thrilling enough for a horror film, the “Death Note” movie becomes a gorefest almost immediately. Light decides to see if a school bully will truly be decapitated if he writes that on a blank page, and Wingard gleefully stages the ensuing carnage like he’s planning to reboot the “Final Destination” franchise next. In the film version, Light does move back to “justified murder,” but even those are Horror Extreme, taking out the man who got away with killing Light’s mother and a criminal holding hostages—both in brutal ways.

The biggest change in the film version of “Death Note” is the inclusion of a romantic arc with another high school girl named Mia (Margaret Qualley), who is quickly let in on the Angel of Death Game because Light has a crush on her. (One could argue that this character is a version of the manga’s Misa Amane, an eventual companion for Light in the books but the character’s history and purpose are radically different.) And the pair soon get a nemesis in the mysterious “L” (Keith Stanfield), who tracks the God of Death known in the press as Kira. One of the best elements of the manga was the cat-and-mouse between Kira/Light and L, but that’s greatly diffused here by the addition of Mia and the changes made to Light’s family, including his police chief father (Shea Whigham).

And here’s where we get back to the fatal flaw of “Death Note”: it doesn’t feel like any of these alterations to the source material, and there are many of them, had true artistic or thematic purpose. Why make this or that change? Why add this character or change this plot point? If there’s no true answer, it’s all just a hollow exercise. And the biggest problem is that Wingard and company clearly refused to make Light the antihero he needed to be, and so they add a love interest and pervert the entire concept, leaving the project hollow at its center.

Wingard has been a gifted, exciting genre director before with works like “The Guest” and “You’re Next,” but this is misguided in every way. It could be due to years of rewrites of a massive piece of source material, but this movie is a mess on every level, particularly its script. The dialogue truly sucks—“We could change the world.” “We? As in us?”—but, worst of all, Wingard and his writers never figured out what to do with Ryuk. Yes, a spiky demon voiced by Willem Dafoe is actually boring. Ryuk is a great character, a wisecracking demon who’s fascinated with the flexible morality of human beings. The film version doesn’t know what to do with him, sidelining him until it’s time to turn him into a plot point. Even Ryuk himself looks bored. Given the weird bursts of humor and eccentricity in the final project (ex., L’s partner-in-crimesolving Watari sings him “Optimistic Voices” from “The Wizard of Oz” to put him to sleep), it’s stunning how few of them come courtesy of Ryuk. In fact, when the oddity of the “L” character is injected into the film (and, to be fair, Stanfield is, as he often is, the best thing about this project) one realizes just how tonally screwed the whole thing is.

Most depressingly, given the quality of some of his work (even “Blair Witch” has some interesting pieces), the filmmaking here is sporadic, amateurish and haphazard. Wingard verges on black comedy but then pulls back, unsure of what the tone should be of the piece overall. The final scenes are so horrendously constructed and edited that one has to believe the project was rushed or re-shot. And the ending will have you switching off your Netflix app in disgust. If you don’t die from boredom before you get there.