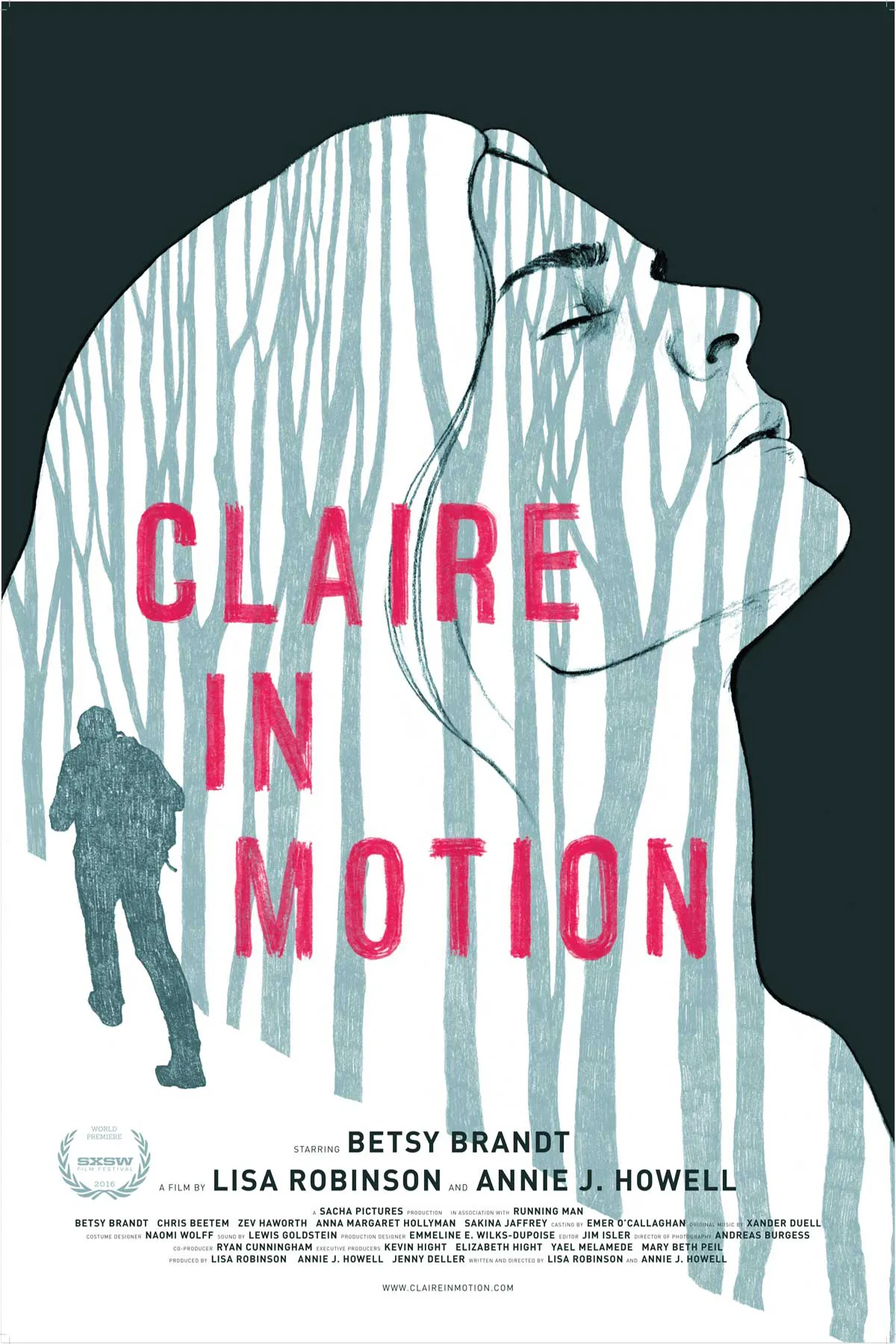

You could program a great double feature with the two films directed so far by Annie J. Howell & Lisa Robinson. Their first movie, 2011’s “Small, Beautifully Moving Parts” was a sunny SXSW selection about a pregnant woman/tech-geek trying to track down her estranged mother in order to get some answers about motherhood. Their latest feature, “Claire in Motion,” is of a similar interest but with a distinct change in tone: the missing person is the title character’s husband, and the questions that art professor Claire has about his whereabouts, or his past, may never be answered. With their second success, Howell & Robinson continue to treat mainstream log-lines with unique emotional and intellectual tenderness, offering a fresh take on our inherent need for closure.

Betsy Brandt gives a compelling performance as the title character whose spirit is slowly breaking, a woman of the arts faced with a painful and personal manifestation of ambiguity. It is not long into the story in which the search is called off for Paul, as a policeman tells her that he very well could have fallen down a crevice in the woods, and there’s no sense in risking lives to find out. She tries to have some type of control of her sanity, which she later calls a means of survival. Later with a friend, she talks about art and Paul’s disappearance as if they were the same thing: “There’s so much uncertainty, and we’re immersed in it.” With a quiet helplessness, as articulated strongly by Brandt, she keeps prodding the mystery, taking her son (Zev Haworth) out to the woods where he disappeared in hopes of finding something, or watching an iPad video he made of her, where some marital tension is apparent.

Whatever clarity she does find is then obscured by the presence of an affable art student named Alison (Anna Margaret Hollyman, the lead in “Small, Beautifully Moving Parts”), who is completely new to Claire but knows a lot about Paul, and has even made elaborate art pieces with him. This becomes a key part of the story, but Howell & Robinson treat the “other woman” story thread with vital nuance. They highlight how Alison is an ideological and social opposite, which might mean nothing, or it might mean everything. Alison takes on the world with openness, and that very attitude can make her over-share what she’s thinking to Claire, all in a bungled attempt at being self-aware. Like when Alison shuts down the possibly adulterous elephant in the room early on, she makes things worse in part because of a simple, very human flaw of communication. We don’t know for sure if Alison is telling the truth, but we recognize how she might be trying very hard to do so.

As the mystery about Paul persists, Claire occupies a crushing emotional purgatory. Howell & Robinson accompany this with a thickly overcast color palette, which becomes a sustainable narrative element however slow the story may go. As it fittingly immerses the viewer in uncertainty, the desaturated world of “Claire in Motion” can leave a mark. It becomes a ghostly work, about a woman haunted by a loss more vicious than death.

Howell & Robinson’s film so craftily resists expectation that its more common visual tropes (visions of Paul that are obviously dreams) can hold the story back. But there’s just enough energy in atmosphere and performance within “Claire in Motion,” as with “Small, Beautifully Moving Parts,” that they allow the viewer to settle in and dig deep. I hope we get to see more from them soon.