The central image in “Brassed Off” is that of a face: shiny, homely, dead serious. It is the face of a man who earnestly believes he is doing the most important thing in the world. The man’s name is Danny, and he is the leader of a brass band made up of coal miners who work at a pit in Grimley, a Yorkshire mining town. The band was founded in 1881, and its rehearsal room is lined with the photographs of past bandmasters, looking down sternly on the current generation of musicians.

It is 1992, and the colliery is about to be closed. The Conservative government made a decision some years earlier to replace coal with nuclear power as a source of fuel, and as a result some 140 pits, representing more than 200,000 miners’ jobs, were declared redundant. The closure of a pit means the death of a town, because a village like Grimley depends entirely on the wages of the miners, whose families for generations have gone down in the mines–and played in the band.

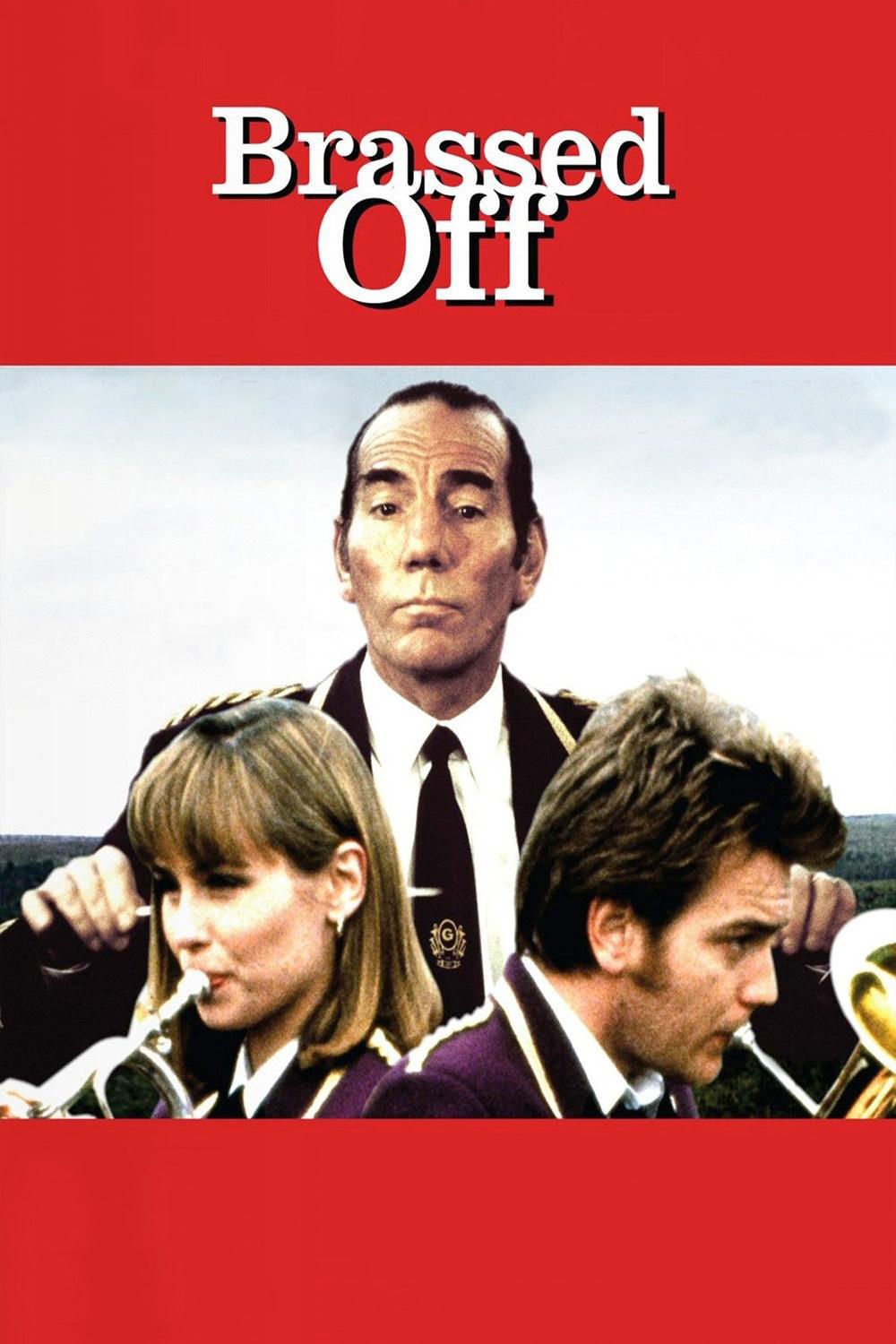

“Brassed Off” is a film that views the survival of the town through the survival of the band, and the survival of the band through the eyes of Danny (Pete Postlethwaite), who in some corner of his mind probably believes the mines exist only to supply him with musicians. The movie makes liberal use of storytelling formulas (there is a love story involving young people, and a crisis involving a married couple, and a health crisis involving Danny, a strategic use of “Danny Boy,” and a national band contest at the Royal Albert Hall). But Postlethwaite’s performance elevates and even ennobles this material.

He loves music. He is stern and exacting about it. His band members may labor in the pits all day, but when they come to rehearsal he expects seriousness and concentration. There is a 14-town competition coming up, and then the national finals, and this year he thinks the Grimley Brass Band has a real chance. If the pit closes, it will be a last chance.

Into the rehearsal hall one day comes a pretty young woman named Gloria (Tara Fitzgerald), who asks if she can sit in with her flugelhorn. She can. Her late father had been the band’s best flugelhorn player, and her performance of “Rodrigo’s Concerto” brings tears to the eyes of some of the band members–and a sparkle to the eye of young Andy (Ewan McGregor, from “Trainspotting”), who had a crush on her in school. Now she has gone away to London, and returned to Grimley (we learn) to make a study about the pit closure.

She pretends to have forgotten Andy, but later admits, “I did know your name–I just didn’t want you to think it was etched forever on my brain.” The love they felt when they were 14 blossoms again, until it is revealed that she is working for the other side–for the government agency that would close the mine. She protests that she is on the miners’ side, and that her study might save the pit, but is told scornfully, “It’s just a bloody PR exercise.. They’ve already made their decision while you were at bloody college.” Another important figure the story is Phil (Stephen Tompkinson), Danny’s son, who struggles to make ends meet for his wife and large family. He wants to quit the band in order to save paying the dues, but lacks the nerve to tell his father. Phil moonlights as Chuckles the Clown, and brings a quick end to a children’s birthday party with an uncontrolled outburst against Margaret Thatcher.

“Brassed Off” is a sweet film with a lot of anger at its core. The writer and director, Mark Herman, obviously believes the Tory energy decisions were inspired by the fact that coal miners voted Labour while nuclear power barons were Conservative. His plot tugs at every possible heartstring as it leads up to a dramatic moment in the Royal Albert Hall, which I will not reveal; it includes a speech against Thatcherism that some British critics found inappropriate, although it’s certainly in character for old Danny.

One of the movie’s great pleasures is the music itself. Brass bands are maintained by many different British institutions–schools, police forces, military units, coal miners, assembly-line workers–and their crisp music always seems gloriously self-confident. Some of the film’s best shots show Pete Postlethwaite’s face as he leads the band: his anger when members get drunk and miss notes, and his pride when everything is exactly right. Acting is not accomplished only with words and emotion. Sometimes it is projected from within, into a stance or an expression. There is not a moment in “Brassed Off” when I did not believe Postlethwaite was a brass band leader–and a bloody good one.