“Behemoth” opens with a distant shot of some kind of excavation project. Mechanical shovels and earth-movers sit on ridges of land carved out by other machines and while all is still for a short time, that quiet is torn apart by a loud explosion that sends sheets of dust into the air. Black and red and grey and yellow dust. It’s beautiful, just as the strafing of a tropical shoreline at the opening of “Apocalypse Now” was beautiful. Catastrophe seen from afar sometimes looks positively awe-inspiring.

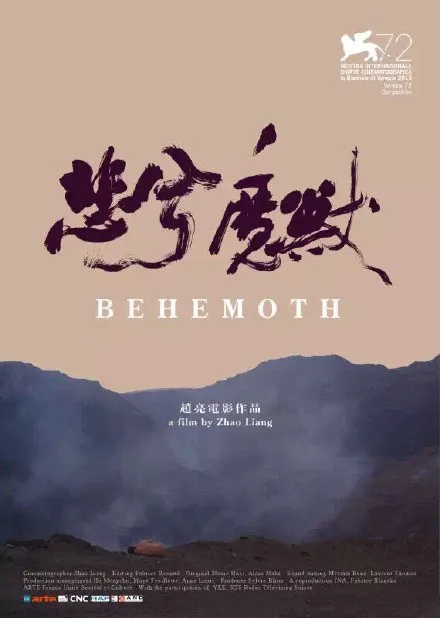

This film, directed by Zhao Liang (acclaimed here for his 2009 “Petition”) is a kind of poetic documentary. It’s all images and sounds, no interviews, no talking heads. Its most direct precursor, I suppose, is Werner Herzog’s 1992 “Lessons of Darkness,” which looked at the set-afire Kuwait oil fields in the aftermath of the first Iraq War, framing its narrative, such as it was, as that of a science-fiction film. In “Behemoth,” Liang looks at the ecological and human disasters created by greedy government malfeasance through the lens of Western concepts of Heaven and Hell and the Fall. Starting many of his scenes by having a naked man—an Adam—lying on his side in the landscapes Liang shoots, the movie is punctuated by texts that Liang and co-writer Sylvie Blum adapted from Dante’s Inferno.

Multiple shots of explosions accompanied on the soundtrack by Tuvan throat singing briefly bring to mind Antonioni’s death-to-the-West ending of “Zabriskie Point.” But Liang here is mourning, or reeling back in terror. The mine seen early in the movie yields its contents, which is trucked to a hillside by large trucks that dump it on a stories-high pile. From that pile, smaller trucks take the coal and transport it elsewhere. The site is right next to a verdantly green and lush series of hills where lamb graze and frolic, oblivious to the fact that their paradise is not long for this world.

Liang’s camera—the director shot the movie himself, at, it seems, some considerable risk to his own safety—then descends to beep within mines, then to refineries, where ore is transformed at punishingly high temperatures into steel. He accompanies individual miners and refinery workers to the quarters where they live. They are miserable, barren places where the workers, both male and female, try to scrub the fortified dirt out of their pores before they go to sleep. In the Asian system depicted by Liang, there’s no having-a-beer-with-the-guys break from work. Work, clean, eat a little, and sleep is how it goes. The narration notes, “Where wealth accumulates and man is uprooted all is decreed by this monster,” the “Behemoth” of the title. The workers only comment with their eyes.

The cinematography is matched by the amazing soundtrack, an aural hellscape in which it’s hard to distinguish between diegetic sound and music, or “music.” The movie’s haunting finale shows where all this industry winds up. After that, “Behemoth” breaks away from its poetic mode and shows some workers from Sichuan huddled in front of a government building, protesting their working conditions. Many of them suffer from pneumoconiosis, a lung disease brought on by breathing in all the beautiful dust that the explosions kick up.

This is a beautiful and harrowing movie, the first of the bad-news-for-humanity documentaries to be released in the states this year. Drink up!