The term antichrist is commonly used to mean “the opposite of Christ.” It actually translates from the original Greek as “opposed to Christ.” This is a useful place to begin in considering Lars von Trier’s new film. The central character in “Antichrist” is not supernatural, but an ordinary man, who loses our common moral values. He lacks all good and embodies evil, but that reflects his nature and not his theological identity.

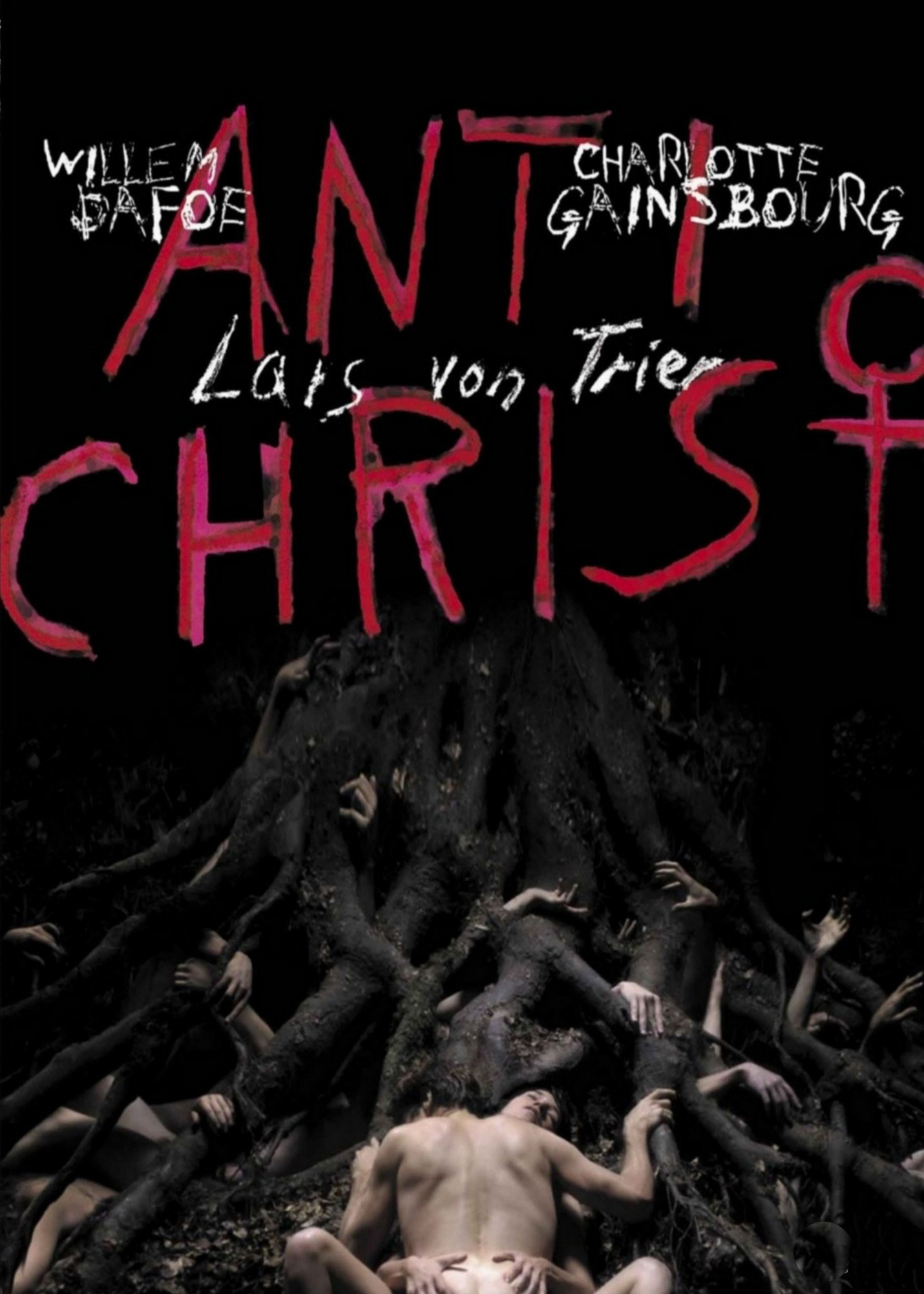

This man, known only as He, is played by Willem Dafoe as a somber, driven, tortured soul. The film opens with He and his wife, She (Charlotte Gainsbourg), making passionate love. This is a moment of complete good. In the next room, their infant son begins to crawl around to explore and falls to his death. This in itself is a neutral act. It inspires the rest of the film, which labels itself in three stages: Grief, Pain and Despair.

We must begin by assuming that He and She are already at psychological tipping points. She has been doing research on witchcraft, and it leads her to wonder if women are inherently evil. That may cause her to devalue herself. He is a controlling, dominant personality, who I believe is moved by the traumatic death to punish the woman who delivered his child into the world.

Their first stage, Grief, is legitimate. Their error is in trying to treat it instead of accepting it and living it through. Of course they blame themselves for having sex when they should have been attentive to the infant. Guilt requires punishment. She mentally punishes herself. For reasons he may not be aware of, he is driven to deal with her guilt as a problem, lecturing her in calm, patient, detached psychobabble. Her grief is her fault, you see, and he will blame her for it.

This leads to pain, most directly when he insists, at this of all times, on their going to their remote cabin in a dark woods that she fears at the best of times. The cabin is named Eden; make of that what you will. They have already eaten of the fruit, and it will never be Eden for them again.

The psychic pain of his counseling and their removal to the forest are now joined by pain inflicted upon them by nature and each other. The woods are inhabited by strange animals that look ordinary — a deer, a fox, a crow — but are possessed and unnatural. He and She don’t much seek refuge in their cabin but increasingly find themselves outside in the wilderness. They begin to inflict pain on each other in unspeakable and shockingly intimate ways.

These passages have been referred to as “torture porn.” Sadomasochistic they certainly are, but porn is entirely in the mind of the beholder. Will even a single audience member find these scenes erotic? That is hard to imagine. They are extreme in a deliberate way; von Trier, who has always been a provocateur, is driven to confront and shake his audience more than any other serious filmmaker — even Bunuel and Herzog. He will do this with sex, pain, boredom, theology and bizarre stylistic experiments. And why not? We are at least convinced we’re watching a film precisely as he intended it, and not after a watering down by a fearful studio executive.

That said, I know what’s in it for von Trier. What was in it for me? More than anything else, I responded to the performances. Feature films may be fiction, but they are certainly documentaries showing actors in front of a camera. Both Dafoe and Gainsbourg have been risk takers, as anyone working with von Trier must be. The ways they’re called upon to act in this film are extraordinary. They respond without hesitation. More important, they convince. Who can say what von Trier intended? His own explanations have been vague. The actors take the words and actions at face value and invest them with all the conviction they can. The result, in a sense, is that He and She get away from von Trier’s theoretical control and act on their own, as they are compelled to.

We don’t know as much as we think we do about acting. In a recent interview, I asked Dafoe what discussions he had with Gainsbourg before their most difficult scenes. He said they discussed very little: “We had great intimacy on the set but the truth is we barely knew each other. We kissed in front of the camera the first time, we got naked for the first time with the camera rolling. This is pure pretending. Since our intimacy only exists before the camera, it makes it more potent for us.”

So it is a documentary in one way. What does it document? The courage of the actors, for one thing. The realization of von Trier’s images, for another. And on the personal level, our fear that evil does exist in the world, that our fellow men are capable of limitless cruelty, and that it might lead, as it does in the film, to the obliteration of human hope. The third stage is Despair.