Americans didn’t know we had the right idea, but we did. We welcomed those from foreign lands (or, in some cases, forced them to come here). Then we shook them up together and left them to sort things out. We have every race, ethnicity and religion, and that helps. Unhappy are those who live in a land with only a few.

Consider Israel, where Jews, Arabs, Muslims and Christians by and large think it is extremely important that they are Jews, Arabs, Muslims and Christians. There is a growing minority that thinks, hey, here we all are together, and since nobody is budging, let’s get along. But most apparently think someone should budge, and it’s not them.

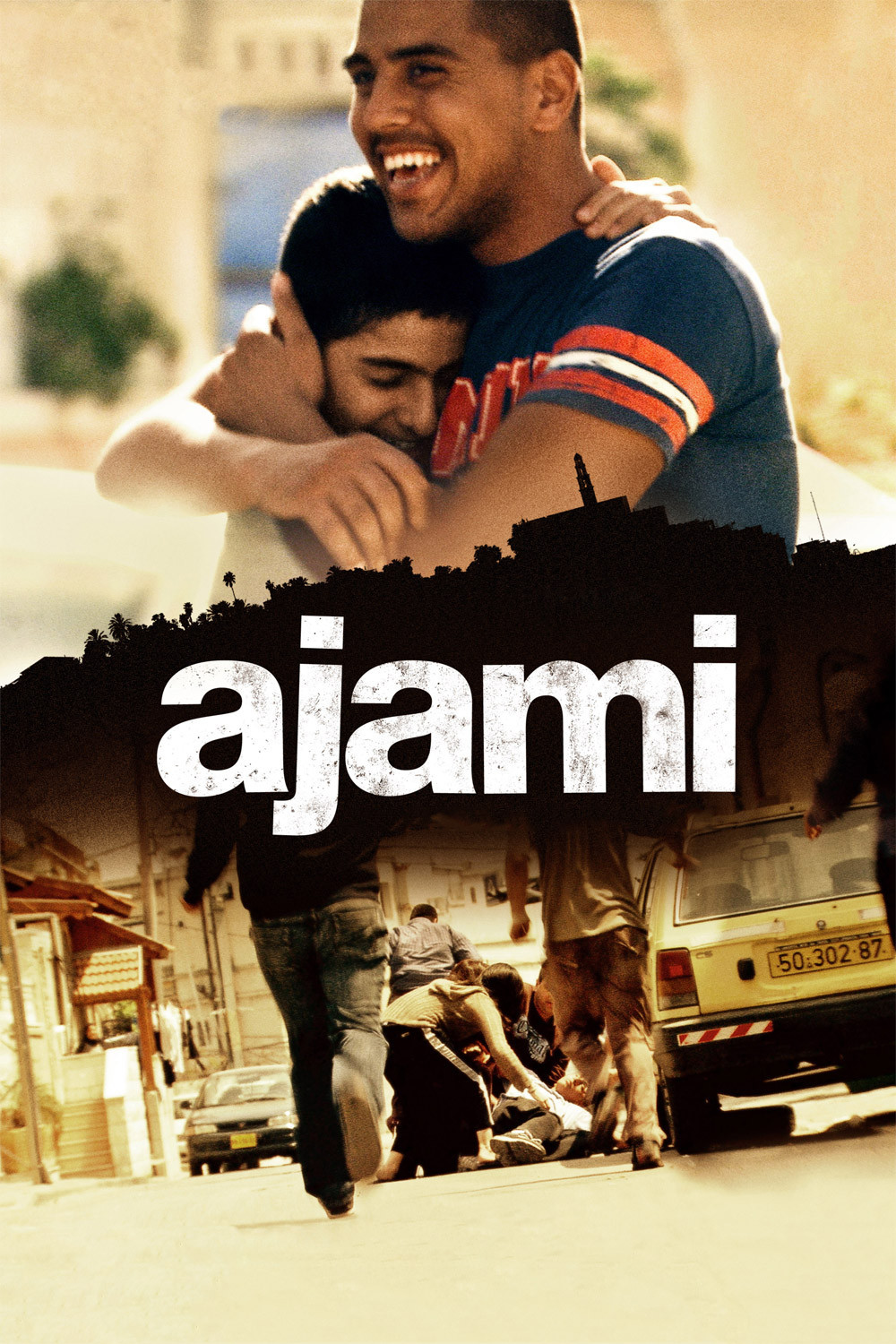

“Ajami,” one of this year’s Oscar nominees for best foreign film, is the latest and one of the most harrowing films set along the religious divides in Israel. It was co-written and co-directed by an Israeli and a Palestinian, and set in Jaffa, technically a part of Tel Aviv, which has high crime and unemployment rates. The focus is on mean streets that Scorsese might understand. Gangsters, cops and drug dealers are tossed in with religious conflicts, and the ancient Romeo and Juliet quandary. God help anyone who marries outside their tribe.

I have never seen a film from either Israeli or Palestinian filmmakers that makes a case for anything other than co-existence. There are probably such films arguing the opposite. But the dominant theme is the tragedy of the social divides, the waste, the loss, the violence that often claims the innocent.

Why, in an area where tension and indeed hatred runs so high, aren’t there more partisan or sectarian films? Beginning with the advantage of ignorance, I’ll speculate that those Palestinians and Israelis who are inclined to make feature films are drawn from the elites of their societies. They see more widely and clearly. They may be better educated. They are more instinctively liberal. They’ve grown beyond the group mentality.

Ah, but there is still the element of family. No matter how advanced one’s views, blood ties run deep, especially when reinforced by religion. A couple may fall in love outside their tribe, but their fathers, uncles and cousins will likely feel threatened by their love, and the gods will be invoked on both sides. It is the same when a relative is murdered. Instincts demand revenge.

“Ajami” is about an interlocking series of such situations, starting in the first place when a man is shot dead. Then another man is mistakenly killed in revenge. Was he mistaken for the original killer? No, he was mistaken for a member of the original killer’s family — which he was, although not the correct member. Now two people are dead, more vengeance is required, nothing has been proven, and everyone involved is convinced they are in the right.

Calm heads try to prevail and stop the killing. The actual original killer (are you following?) is levied with a fine. To pay it, he finds he must sell drugs. That means we are now headed into gang territory. The source of the drugs is a Palestinian in love with a Jewish girl. An Israeli cop becomes involved in the case. I won’t describe more. I’m not sure I can. It’s clear enough in the film who is who, but I suspect even the characters lose track of the actual origins of their vendettas. What happens is that hatred continues to claim lives in a sort of domino effect.

The film doesn’t reduce itself to a series of Mafia-style killings, in which death is a way of doing business. There are situations in which characters kill as a means of self-defense. And the filmmakers, Scandar Copti and Yaron Shani, by and large show characters on all sides who essentially would like simply to be left alone to get on with their lives. Few of them possess the personal hatred necessary to fuel murder. But the sectarian divide acts as an artery to carry murder to everyone downstream. Was that a mixed metaphor, or what?

The specifics of the plot in “Ajami” aren’t as important as the impact of many sad moments that build up one after another. Hatred is like the weather. You don’t agree with the rain but still you get wet. What justifies this is the “honor” of your family, your religion, your tribe. The film deplores this mentality. So do we all, when we stand back and think. The film has no solution. Nor is there one, until people find the strength to place more value upon an individual than upon his group. Sometimes I fear we’re all genetically programmed not to do that. One solution is the mixing of gene pools so that groups are differently perceived. But I’m not holding my breath.