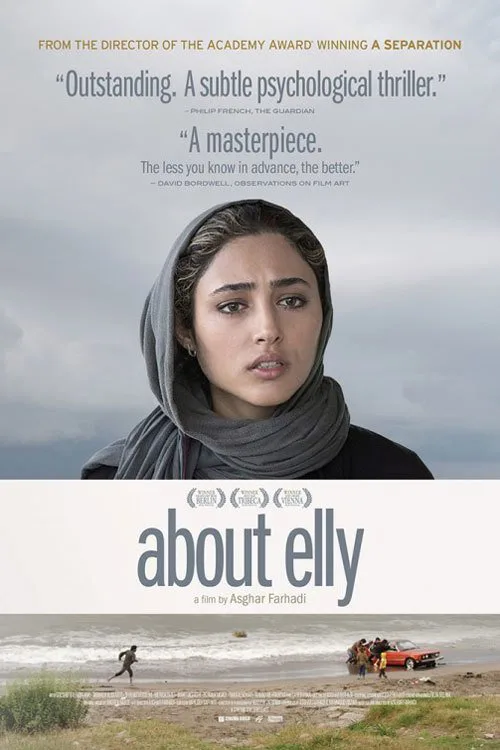

At the end of act one in Asghar Farhadi’s gripping “About Elly,” the title character disappears. Elly (Taraneh Alidousti), a young school teacher, has gone on a weekend vacation with a group of thirtysomething professional couples from Tehran. She’s supposed to be looking after three little kids who’re playing on a beach, and suddenly she’s not there. That this vanishing sets up a mystery that propels the rest of the film has led to understandable critical comparisons to Antonioni’s “L’Avventura.”

Yet the scene that immediately follows our last glimpse of Elly reminded me of quite a different movie: Spielberg’s “Jaws.” Most of the vacationing adults are playing volleyball behind the villa where they’re staying when two of the aforementioned kids appear from the beach and start screaming about the third. It takes the grownups several beats to catch on, but when they do, they rush around the house, realize that the third kid, a little boy, is nowhere to be seen, and frantically begin plunging into the Caspian Sea’s crashing waves.

I won’t reveal how the scene ends, just that I can’t help but think Spielberg would admire Farhadi’s electrifying direction of it. As the Iranian men dash into the ocean, and their alarmed wives emerge from the house, everything is in motion: the characters, the water, the camera. We seem to be looking in every direction at once, desperately: up and down the beach, back toward the villa, even under the sea as it pounds forward violently. Farhadi’s orchestration of all these elements is complex and viscerally kinetic; few viewers will experience it without holding their breath at some point.

So what do we make of an Iranian film whose conceptual parameters are broad enough to span “L’Avventura” and “Jaws”? Perhaps we should begin by venturing that Asghar Farhadi is a new and conspicuously audacious kind of Iranian auteur. When Iranian directors such as Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf began catching the world’s eye in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, it was for films that had obvious parallels to Euro-style cinematic modernism. Even when newer directors including Jafar Panahi and Majid Majidi gave a more commercial spin to this basic model from the late 90s onward, their work still spoke the language of the international art film.

Farhadi’s “A Separation” (2011) took a different tack, becoming the most successful Iranian film in history, as well as the first to win the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, thanks in part to innovations on two fronts. First, Farhadi’s Iranian cinematic models were not any of the aforementioned filmmakers but two cinematic masters who are less well known outside Iran: Dariush Mehrjiu (“Leila”), whose films often deal with Iran’s middle and upper classes; and Bahram Beyzaie (“The Travelers”), whose creative roots are in theater (as are Farhadi’s). Second, Farhadi admitted American influences including the likes of Elia Kazan and films such as “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

“About Elly” represents all the tendencies of Farhadi’s mature style as brilliantly as “A Separation,” yet it is not a successor to the latter film. It was made just before it and won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival in 2009, but, due to complicated rights issues, was not released in the U.S. until now. Its belated appearance should be welcomed by cinephiles, as it offers solid proof of this writer-director’s distinctive gifts.

One of those is a way of dramatic structuring that’s like peeling an onion: the first layers we see seem familiar and self-evident, but the more layers we reach, the more complex the whole becomes. Here, the starting point is what seems like an entirely happy and carefree outing where three couples – many of whom have been friends since law school – motor out to the Caspian Sea for a holiday weekend. One wife has invited along pretty Elly, her daughter’s elementary school teacher, in obvious hopes of matching her with the excursion’s other singleton: Ahmad, a handsome friend who’s just returned from Germany after getting divorced.

For Americans who’ve seen few Iranian films, or only ones centered on the poor or dispossessed, the characters here will be striking. With their BMWs, faded t-shirts and constant joking around, they’re like cosmopolitan urbanites anywhere. Sure, we’re reminded of their Iranian-ness in their particular styles of music and dance and in the fact that the women all wear head-scarves throughout (something required by law of Iranian films) but even they are casual and stylish.

As in “A Separation,” there’s evidence of tension between this class of privileged professionals and the strata of poorer, more pious Iranians beneath them, but this is more peripheral than in the later film: e.g., the Tehranis pretend Elly and Ahmad are newlyweds in order not to offend the religious sensibilities of the rural folks who rent them the villa.

From that little white lie to other similar ones and the uncovering of various personal agendas: the peeling away of the onion skins reveals a continuing succession of hidden realities, and the ones that come after Elly’s disappearance are darker and cut deeper than those early on. But when I read that a writer in Sight & Sound has said all this constitutes “a critique of the lies and evasions that permeate Iranian society,” I can practically hear the groans coming from Farhadi, who has said in interviews that he doesn’t want to be one of those filmmakers who is expected “to explain Iran to the West.”

The filmmaker has, instead, clearly indicated that his goals in “About Elly” are far less sociopolitical than cinematic, stating that, “[D]irectors can no longer be content with force-feeding [audiences] a set of preconceived ideas. Rather than asserting a world vision, a film must open a space in which the public can involve themselves in a personal reflection, and evolve from consumers to independent thinkers.”

“Opening spaces” is precisely what Farhadi’s films do, both literally and figuratively. Indeed, the various ways great Iranian directors articulate visual space comprise one of the most fascinating and significant dimensions of Iranian cinema, from the contemplative and symbolic uses in some films to the poetic and documentary-like in others.

Farhadi’s way with space is more dynamic and consciously multi-layered, as well as technically virtuosic, enough so to recall “Jaws” or indeed “A Streetcar Named Desire.” To anyone going to see “About Elly,” I would say this: Notice the early scene where the four couples and three kids arrive at the villa with the boy whose family is renting it to them. See the way ace cinematographer Hossein Jafarian’s gliding hand-held camera takes in the disheveled rooms, glimpses the seascape through the windows and doors, and sets up an enormously complex and involving set of relationships between the characters by continually reframing them.

There are some great little moments here. Two quick shots of the host boy, for instance: in one, he glances out the front door at two kids on the beach, prefiguring the lost-child scene described above; in another, he gives a brief caustic look in reaction to one Tehran man’s silly dance – a statement of class differences as eloquent as any dissertation.

Farhadi is a masterful director of actors, and here he gets a range of precise, vivid performances from a cast that also includes Golshifteh Farahani, Peyman Moadi (“A Seperation”), Mani Haghighi and Shahab Hosseini. It might be argued that Farhadi doesn’t have any grand message, or “world vision” as he puts it. But to me, his way of revivifying cinema, and connecting its spaces to those of human hearts and minds, is vision aplenty.