The little girls had gone to church early for choir practice, and we can imagine them, dressed in their Sunday best, meeting their friends in the room destroyed by the bomb. We can fashion the picture in our minds because Lee has, in a way, brought them back to life, through photographs, through old home movies and especially through the memories of their families and friends.

By coincidence, I was listening to the radio not long after seeing “4 Little Girls,” and I heard a report from Charlayne Hunter-Gault. In 1961, when she was 19, she was the first black woman to desegregate the University of Georgia. Today she is an NPR correspondent. That is what happened to her. In 1963, Carole Robertson was 14, and her Girl Scout sash was covered with merit badges. Because she was killed that day, we will never know what would have happened in her life.

That thought keeps returning: The four little girls never got to grow up. Not only were their lives stolen, but so were their contributions to ours. I have a hunch that Denise McNair, who was 11 when she died, would have made her mark. In home movies, she comes across as poised and observant, filled with charisma. Among the many participants in the film, two of the most striking are her parents, Chris and Maxine McNair, who remember a special child.

Chris McNair talks of a day when he took Denise to downtown Birmingham, and the smell of onions frying at a store’s lunch counter made her hungry. “That night I knew I had to tell her she couldn’t have that sandwich because she was black,” he recalls. “That couldn’t have been any less painful than seeing her with a rock smashed into her head.” Lee’s film re-creates the day of the bombing through newsreel footage, photographs and eyewitness reports. He places it within a larger context of the Southern civil rights movement, and sit-ins and the arrests, the marches, the songs and the killings.

Birmingham was a tough case. Police commissioner Bull Connor is seen directing the resistance to marchers and traveling in an armored vehicle–painted white, of course. Gov. George Wallace makes his famous vow to stand in the schoolhouse door and personally bar any black students from entering. Though they could not know it, their resistance was futile after Sept. 15, 1963, because the hatred exposed by the bomb pulled all of their rhetoric and rationalizations out from under them.

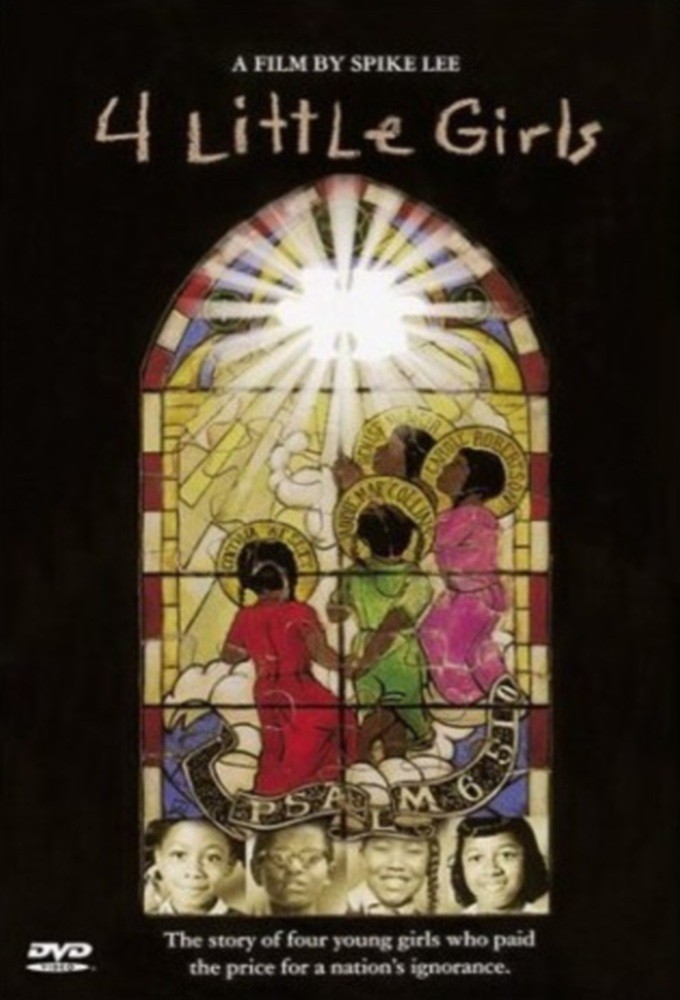

Spike Lee says he has wanted to make this film since 1983, when he read a New York Times Magazine article by Howell Raines about the bombing. “He wrote me asking permission back then,” Chris McNair told me in an interview. “That was before he had made any of his films.” It is perhaps good that Lee waited, because he is more of a filmmaker now, and events have supplied him a denouement in the conviction of a man named Robert Chambliss (“Dynamite Bob”) as the bomber. He was, said Raines, who met quite a few, “the most pathological racist I’ve ever encountered.” The other victims were Addie Mae Collins and Cynthia Wesley, both 14. In shots that are almost unbearable, we see the victims’ bodies in the morgue. Why does Lee show them? To look full into the face of what was done, I think. To show racism its handiwork. There is a memory in the film of a burly white Birmingham policeman who after the bombing tells a black minister, “I really didn’t believe they would go this far.” The man was a Klansman, the movie says, but in using the word “they” he unconsciously separates himself from his fellows. He wants to disassociate himself from the crime. So did others. Before long even Wallace was apologizing for his behavior and trying to define himself in a different light. There is a scene in the film where the former governor, now old and infirm, describes his black personal assistant, Eddie Holcey, as his best friend. “I couldn’t live without him,” Wallace says, dragging Holcey in front of the camera, insensitive to the feelings of the man he is tugging over for display.

Why is that scene there? It’s sort of associated with the morgue photos, I think. There is mostly sadness and regret at the surface in “4 Little Girls,” but there is anger in the depths, as there should be.