This was the kind of night a movie star’s life is made of, a lonely, chill and windy night in a vacant lot somewhere in the middle of a strange city. Sean Connery said he rather enjoyed such nights. We were down near the corner of 46th and Calumet, on Chicago’s South Side, where a film crew had rented a building to shoot some scenes for a movie.

It was past midnight. The L trains that rumbled past had bright, empty windows. For five hours, director Brian De Palma had been working to get a single shot exactly right on the set of “The Untouchables,” a film inspired by the early ’60s television series.

A camera on a crane would move slowly in to look over the shoulder of a gangster lighting a cigarette. Then it would tilt up to look at a man pacing beside a lighted window. Then it would turn to watch the gangster walk down a rain-soaked sidewalk, and then continue watching while another man slipped from the shadows and moved toward the house. A shot like that will occupy a minute or two of screen time, when “The Untouchables” is finally put together. Tonight, it involved hours of preparation and thousands of dollars of fees for the crane, and renting the auditorium of a nearby Baptist church so that dozens of cast and crew members could eat chicken Vesuvio at 3 a.m.

And for Sean Connery, it involved pacing before the lighted window until they finally got the shot exactly right, and then waiting inside a rented mobile home until they were ready to use him again.

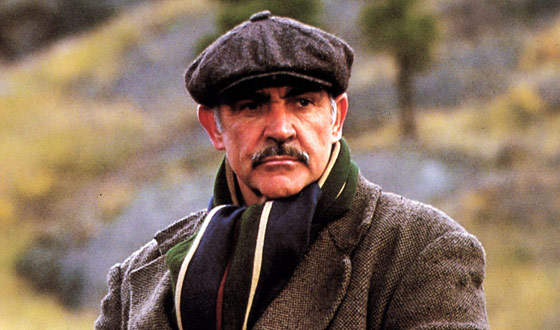

“I’ve had hotel rooms that weren’t half as nice,” Connery said. “I’ve got my little kitchen here, and a refrigerator, and a bedroom, and a toilet, and a sofa to sit on and a color television set to watch.” He sounded resigned rather than cheerful. He is a big man, tall, balding, with the beginnings of a paunch, and he was dressed in baggy tweeds as Malone, a Chicago cop.

“Let’s get some fresh coffee in here,” he said. “This stuff in the pot tastes like paint remover.”

Here is a man who knows the mixed blessing of steady employment. He spent many years looking for success as an actor. He found it in 1962, playing a man named James Bond, and then found he could not escape the role. You could put together a splendid festival of the films in which Connery has not played Bond; the titles would include “Marnie,” “A Fine Madness,” “The Molly Maguires,” “Zardoz,” “The Wind and the Lion,” “Robin and Marian” and the incomparable “The Man Who Would Be King.” But would you be able to forget James Bond? Perhaps middle age is giving him freedom; Connery now looks better, worn and more comfortable within himself; his own sense of humor is wry and gentle, unlike Bond’s arch ironies.

“I don’t mind the night shift, actually,” he said. “The problem is getting the hotel to believe that ‘Do Not Disturb’ really does mean ‘Do Not Disturb.’ The strange thing is being free in the mornings. Tomorrow, for example, I’m to go to a screening in the morning. It feels curious and wrong — was man meant to see films in the morning? And yet all of my early moviegoing was on Saturday mornings, in Edinburgh, where they showed you the latest chapter of a serial named ‘The Clutching Hand,’ and then a Three Stooges cartoon, and then a feature with a title like ‘God Gave Him a Dog.’ It was a real flea pit.”

Was it then that you got the idea that movies would play some kind of a special role in your life?

“Goodness, no. I did many other things before I ever got into the movies. I’ve been in so many businesses, it’s a joke. All of them totally unsuited to me. Selling used cars. Running a club in London. After I began to make some money, my brain-damaged accountant put me in one business after another that went bad. The only one that panned out was a small bank, an old Scottish firm with London offices in Pall Mall. I was a director. We sold out to a larger bank. That was the only successful venture I’ve had, apart from acting.”

He sipped from a mug of black coffee.

“What happened,” he said, “was that the British government was taking 98 percent of my income in taxes. I was making nothing but money, and I was virtually broke. I finally moved to Spain.”

Was it difficult, though, to leave London behind?

“Not at all. I made my break when I moved from Scotland. That was leaving home. Michael Caine moved away and misses London and goes back all the time. When I went away, I stayed away four years.”

And so you’ve become a wanderer, from one movie location to another.

“I quite enjoy it, actually. Chicago has been a surprise. I had never been here and had no idea it was such a beautiful place. I went up to Lake Forest and played golf and came back down along Lake Shore Drive just at sunset on a Sunday, and it really was quite stunning, the coast along the sea. Not the sea, the lake. Well, it looks like a sea. And the skyscrapers here aren’t all arranged in walls, like in Manhattan. You can stand back and see them. I like the little corners, too, where the old city remains. We went to that restaurant, Gene and Georgetti’s, underneath the elevated trains. They had great steaks, and more waiters than I’ve ever before seen in one place at one time. Such a crowd, it was more like American football.”

There are all the ethnic restaurants as well, I said, feeling like a representative of the tourism office.

“Yes. Well. Mexican food, and all that sort of thing? I’ve never really fancied Mexican food, you know. A taco rather minds me of a puncture outfit.”

A what?

“A puncture kit. For patching holes in bicycle tires. It contains all these bits and pieces, hard to identify.”

I had never thought of it that way before, I said. The movie Connery was going to see the next morning, by the way, was “The Name of the Rose,” scheduled to open Oct. 24 in Chicago. The film, set in the year 1327, stars Connery as William of Baskerville, a legendary Franciscan who visits a monastery being plagued by a mysterious series of murders. It is up to him to solve them — and head off the evil Inquisitor (F. Murray Abraham), who assigns all blame to heretics and those possessed of the devil. The movie seems to take place mostly at night inside gloomy monastery walls, where secretive and vindictive men scurry about thinking the worst of one another. It was directed by Jean-Jacques Annaud, who made “Quest for Fire,” and whose characters often seem in the early stages of man’s ascent from the mud.

“I haven’t seen it yet,” Connery said, “and I’m quite curious. God, it was one of the toughest films I’ve ever made. We filmed in Germany in a monastery, and then we built sets on a hillside outside Rome, and of course, there was noise from planes and trains and buses and blimps. We couldn’t record a single line of dialogue that was usable, and so we had to spend 10 days looping every line of the movie. The monastery was so cold, you could see your breath when you spoke, and of course, they wanted that effect. But I wanted to make the film because I loved the book, which sold 4 million copies, although I imagine 2 million of those copies were never finished, because the first 100 pages are rather slow going — although nothing compared to the 10 days we spent dubbing the dialogue.”

He smiled. “Most movies shot in Italian don’t even bother to record the sound. In fact, sometimes when Fellini works, he doesn’t even know what the dialogue is going to be, and he simply has his characters count from 1 to 10, knowing he will loop in their dialogue later.”

Is it rather strange, going from medieval dialogue to the Chicago criminal jargon of the late 1920s?

“Well, one of the things that attracted me to this whole project was the screenplay by David Mamet. I didn’t know much about the Untouchables — except, of course, for the television series with Robert Stack. I remembered a certain style and glamor, from a period when they used dialogue that would sound wrong if it were set either earlier or later. A certain stylized criminal dialogue that Mamet has written so well. The script is a revelvation. He really captures the purity of that sort of speech, of the kind of optimism that a man like Eliot Ness would have needed to take on a man like Al Capone.”

What about your character, Malone?

“An old cop who teaches Ness the Chicago way. I see this young chap and can’t believe that he really intends to take on the mob.”

How does Mamet have you talk to him?

“I ask Ness what he is prepared to do. If you start with these people, be prepared to go all the way. It won’t stop until one of you is dead. Here’s how you get him. If he pulls a knife on you, pull a gun on him. If he sends one of yours to jail, send one of his to the morgue. That’s the Chicago way.”

Connery smiled.

“Almost Biblical.”