Related articles:

Lunch with Otto (1972)

Preminger: The Ottobiography (1977)

HOLLYWOOD — It’s great to see how they do these things.

Carol Channing was supposed to lift Frankie Avalon up in the air, shake him vigorously, and snarl: “Where’s my husband?” Well, Carol is a fairly big girl, and Frankie is about as small as Sal Mineo. But all the same, Carol couldn’t really lift Frankie into the air.

So Otto Preminger called out the carpenters, and they made a seesaw out of a long board and a sawhorse. The idea was that the camera would move in close, the prop men would scamper in on their hands and knees and place the seesaw, Frankie would step on it, and when Carol grabbed his elbows the seesaw would lift him into the air.

It sounded great.

On the first run-through, the prop men pushed down too hard on the other end of the board, and Frankie went sailing up into the air and landed on Miss Channing. On the second take, they got him into the air all right, but he kept bobbing up and down. Besides, Carol was holding him at arm’s length and it looked a little fishy.

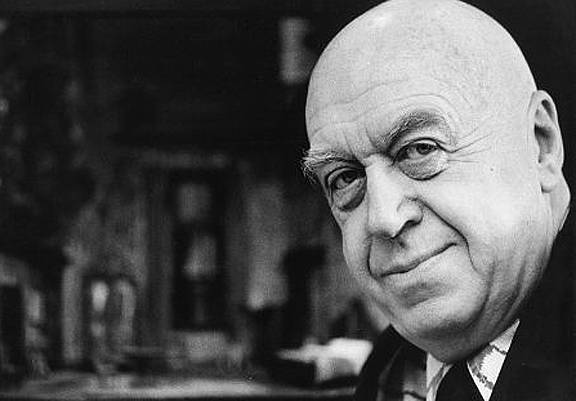

Preminger, whose temper is said to make Genghis Khan resemble Colonel Sanders, moved impatiently onto the set.

“No, no,” he said to Carol, grabbing Frankie by the elbows. “You must hold him like this. Your arms in like this, you see, so that it will look like you are lifting him and not fighting him off. Then lift him like this…”

And with a mighty heave, Otto lifted Frankie off the ground and shook him, shouting: “Where’s my husband?”

Frankie, exhibiting remarkable control, remembered his line from the script: “Aw, leggo.” Preminger dropped him and turned back to Miss Channing. But just then a conversation from off the set became audible.

He marched out of the set and onto the platform, high above the floor of a sound stage at Paramount. A man with a mustache, who turned out to be the representative of the studio head, was talking to a cameraman.

“You!” Preminger roared, pointing an accusing finger at the man. “Out! Get off my set. Yesterday you come and make noise, and today you come and make noise, and that is all! All! If I see you on this set again, I will take my bare hands, and…”

“I hear noise!” Preminger thundered. “Mr. Von Stroheim, do you hear noise?” His nose lifted up as if sniffing out the offending conversation.

“Nothing out here,” said Erich Von Stroheim Jr., Preminger’s first assistant director.

“All the same.” Preminger roared, “I hear noise. I cannot stand noise, and I am the director, and this is my set, and that is my privilege!”

It was not a good day for Preminger, who was deep in the production of his next film, “Skidoo!” The company had just gotten back from San Francisco where they shot Jackie Gleason breaking into Alcatraz. Now it was time for Miss Channing, as Gleason’s wife, to find out from Avalon, a mobster, what the syndicate was doing with her husband.

The set for Avalon’s apartment was a thing of wonder. A barber’s chair and a well-stocked bar appeared from the wall at the touch of a button, Playboy bunnies glowed on the wall, and when another button was pushed, Frankie’s desk slid out of sight and an enormous bed rose from the floor. A typical gangster pad. But things were not going well.

After Miss Channing had lifted Avalon to Preminger’s satisfaction, it was time to shoot the next scene. In this one, Frankie discovers his girlfriend at the door. Where to hide Carol? In the bed, of course, and then push the button and the bed sinks beneath the floor.

On the first run-through, the bed collapsed through the floor with a crash, instead of sinking out of sight with pneumatic bliss. A crowd of prop men disappeared into the floor in search of the bed, and Preminger marched to the telephone to talk to Paramount’s front office.

“Number one,” he shouted, “do not ever let that man on my set again — that what’s-his-name. That’s number one. Number two, the set doesn’t work. The bed falls through the floor. For $51,000, the set ought to work. That’s number two.”

Preminger’s voice echoed through the hushed sound stage. A crew member explained what had happened: “The bed fell, and Otto went over and looked. He just looked.”

Preminger slammed down the phone. The carpenters told him the bed should work now. But Miss Channing was afraid to climb aboard. “It’ll go under the floor and I’ll never be seen again,” she moaned.

Preminger gallantly volunteered to test-pilot the bed himself. He sat in the middle, the button was pushed, and he sank out of sight like a charm. The floor slid smoothly over the bed, and a desk and chair came out of the wall.

“I would hate to think what would happen,” an electrician whispered, “if he got stuck under the floor.”

But the mechanism was now in working order. The desk and chair disappeared, the floor slid back, and the bed reappeared, bearing Otto like Venus rising from the sea. A beatific smile crossed his face, and he spread his hands, palms up. “You see?” he said.

It is often like this when Preminger works.

“He’s as bad as they say,” whispered Alexandra Hay, the young actress who is making her debut in “Skidoo.” “But I guess it’s justified. He does it to get what he wants out of you. He’s an angel one minute, and a dictator the next.”

Indeed, when Preminger presided over the luncheon table, he was so charming that it seemed impolite to refer to the eruptions of the morning. “If I grew an Old Testament beard,” he mused, “perhaps I could play Moses. John Huston grew a beard, and became Noah. There is precedent.”

He talked about a shot he planned for the next day. Jackie Gleason, safely smuggled into Alcatraz, was supposed to contact the mob’s inside man about springing someone else. In one unbroken camera movement, employing dozens of extras, Preminger wanted to show a line of convicts filing along a corridor, turning a corner into the prison cafeteria, getting their food, moving into the lunchroom, sitting down, beginning to eat and planning the prison break.

It would be a complex master shot of the type Preminger is known for: All the actors and extras would have to do everything while the camera performed a tight maneuver. Then, after Gleason was seated at a cafeteria table, all the dialog would have to go correctly. One slip and the scene would have to be started from the beginning again.

“A shot like this looks completely natural,” Preminger said. “It will call no attention to itself, the way a lot of unnecessary editing and many shorter shots would. If you can do it all in one shot, you can tell your story more smoothly.”

But the next day, when the “Skidoo” crew went to an empty Los Angeles jail to shoot the scene, things did not go so smoothly. Preminger rehearsed all morning, drilling the actors and extras. Some would have to step out of line with perfect timing to let the camera into the corridor, then step back behind the camera so that when it wheeled around they would be there. It was most complicated.

For lunch, a catering service offered a choice of short ribs or chicken. Most of the actors and all of the extras ate heartily: a mistake. After lunch, the actors discovered that after getting their plates filled in the prison cafeteria, they were expected to actually eat the food.

“No mouthing,” Preminger ordered. “It will not look real on the camera. I want you to actually chew and swallow the food. If you cheat, I will catch you.”

And so the performers marched down the corridor, through the cafeteria line and into the lunchroom, sat down, ate and talked. They did it once. Then again. Preminger was still not satisfied. Some of the lines didn’t sound right. The cramped space grew hot with the glare of the lights.

In all, there were 21 takes before Preminger was satisfied. Many of the actors, having actually eaten 21 helpings of beef stew under Otto’s watchful eyes, looked ill. Jackie Gleason marched wearily back to his dressing room after the final take, collapsed into a chair, and called for a diet cola.

“Three hours” he said, “See, Preminger likes to get these master shots, and its difficult when there’s more than one. You march through it again and again. Jeez, he’s a perfectionist. How those guys kept eating, I’ll never know. I got to talk. The big guy tried to fake it and Otto caught him. See, Otto has a preconceived notion of how everything has to be. He has it all worked out in his mind, perfect, and then he tries to duplicate that in the camera.”

Gleason drank deeply. “You know what I’d like to make sometimes?” he said. “A Tom Swift movie. And then a movie about Frank Merriwell at Yale. A lot of people don’t know this, but I used to be a Frank Merriwell type.” He laughed. “I started as a trick diver, working with Johnny Weismuller and Buster Crabbe.”

Is it true, as Gleason once said that if everything else fell through he could always make a living by hustling pool?

“I dunno anymore,” he said. “They’re playing pretty good today, and I’m rusty. Still, I guess if I worked at it…”

An assistant director called Gleason to do some close-ups before the day’s shooting was finished. “You know,” Gleason said, “this may not be as tiresome as television, but it’s sure as hell more strenuous. Or maybe it’s the other way around.”

That brought to mind a scene from the previous afternoon, after Carol Channing had finally lifted and shaken Frankie Avalon to everyone’s satisfaction. During a break, she called her husband on the phone.

“How did it go?” she said. “I’ll tell you how did it go. He started yelling and screaming again. But it’s not that. I don’t mind when he yells and screams. But, see, I gotta lift Avalon up in the air, and I couldn’t get it right. I just couldn’t get it right. And he started in on me, yelling and screaming, You know what the trouble was? It was the scene. It’s stupid. Big woman lifts little man, see? Ha ha ha.”