Joel Siegel’s advice for cancer patients

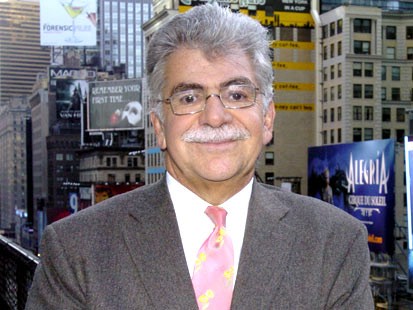

Joel Siegel, the “Good Morning, America” film critic, was a brave man, and a hell of a nice guy. Diagnosed with colon cancer in 1997, two weeks before he learned he was about to become a father, he was given a 60 percent chance of living long enough to see his child. But he fought those odds for a decade, and once told me, “I’ve gone up one side of the bell curve and down the other side, and am now advancing into enemy territory.”

Siegel died on Friday, at 63. A memorial celebration is planned for September. Fearing he would not live long enough to be a father for his son Dylan, he wrote the 2003 book Lessons for Dylan, containing the advice and memories he would have wanted to pass on. But he lived long enough to pass a lot of them on in person.

His cancer spread, then went into remissions, and his friends received regular medical updates. There were four kinds of e-mails from Joel: (1) Good news; (2) Bad news; (3) Encouragement involving your own problems, and (4) Jokes. Mostly we got jokes. If all else had failed, Joel could have been a stand-up comic; in early days, he was a joke writer for Robert Kennedy. On the other hand, he ran a voter registration program for Martin Luther King, Jr., in Macon, Georgia.

But let me tell you a story about how Joel operated. He was good friends with an old college-days friend of mine, CNN’s Jeff Greenfield. One night in New York, the two of them invited me to dinner at Peter Luger’s famous steak house in Brooklyn. They brought along Matt Lauer from NBC’s Today Show.

After dinner, as we were all standing to leave, Joel announced to the packed room, “Ladies and gentlemen, let’s have a round of applause for Roger Ebert!” A day later, the Page Six column ran an item saying that Siegel, Lauer, Greenfield and Ebert had dinner at Luger’s, but when we stood up to go, it was the out-of-towner Ebert who got a standing ovation. Siegel planted the item, of course. “He had it all figured out,” Greenfield told me.

Remembering his friend, Greenfield said: “He was as full of life as anyone I’ve known. A new film, a new book, a new joke — even better, an old joke — was a source of wonder, amazement. Liars and hypocrites — artistic, political, and media versions — triggered outrage; how could people behave this way? The sight of a friend, the recollection of what his son Dylan had said or done — triggered pure joy. God I am going to miss him.”

From the first day I met him, when he was a network star and I was only, well, an out-of-towner, Joel was a friend. We worked the red carpet every year at the Oscars, interviewing each other when things got slow. Chaz and I had dinner with Joel and his wife, the well-known artist Ena Swansea, soon after he got the bad health news, but he wasn’t downbeat; he had hope and determination.

In Lessons for Dylan, he wrote about his feelings soon after hearing his diagnosis:

“I remember looking out the hospital window at a tree, a tree that had somehow managed to grow large and lush even though its seed had somehow taken root on a two-foot wide spit of land between the FDR Drive, one of the busiest highways in America, and the East River, one of the most polluted bodies of water in the world. And I remember thinking about the impossible coincidences that come together to create the miracle of life.”

You can tell from that paragraph, and from the whole book, that Joel was a better writer than you might guess from TV. A cum laude graduate from UCLA, he was at one time book critic of the Los Angeles Times, and among his other jobs was dreaming up new ice cream names for Ben & Jerry’s. But he loved TV and he loved sharing the news about a great new movie. After the death of my TV partner Gene Siskel (another of Joel’s friends), he sat in on the program several times as a guest critic, for the union minimum payment. He was doing a favor for a friend, and for the memory of a friend.

In 1991, he and actor Gene Wilder founded Gilda’s Club, named for Wilder’s late wife, the comedienne and cancer victim Gilda Radner. The club’s purpose was to support cancer survivors and their loved ones. “He used his visibility to raise awareness,” said Lisa Nesselson, a critic for Variety. “While steering people to worthwhile films was our job, steering people toward pre-emptive testing for treatable conditions was infinitely more valuable in the long run.”

Knowing what he knew about the disease, Joel was haunted with questions after his diagnosis. He wrote: “It took me eight years to get the guts to ask my oncologist if I’d had [a colonoscopy] at 50 instead of 53, what would have happened. He said there was a 75 percent to 80 percent chance they would have nipped it in the bud, and I never would have had to deal with any of them.” It was because of Joel that I got my own colonoscopy.

Siegel focused on positive thinking, on visualizing the people and places he loved. During the worst of my own recent illness, he was in frequent communication with Chaz, giving her pep talks, encouraging her in the role of “primary care-giver,” and of course e-mailing her a lot of jokes. At one point he quoted Molly Ivins on the treatment for cancer: “First they abuse you. Then they poison you. Then they burn you. I’ve had worse blind dates.”

We spoke with Ena on Wednesday night. I said I was planning to write a tribute. “Be sure to put in that he was a troublemaker,” she said. “He really enjoyed ripping into a bad movie. He spoke truth to power. He was so sad that true film criticism was being replaced by ‘entertainment news,’ when they only get interviews if their review is laudatory, or they don’t review at all.”

Siegel continued to review until very near the end, writing to us: “How do we do it? We work. We write. We see a movie. Sometimes we think about what we’ve seen. I’m amazed at my ability to go on the air, a pouch in my right hand pumping chemo into a port in my chest, and I go on.” Eventually the chemo took such a toll that “he sensed that something was changing,” Ena told us. “He was a natural optimist. He never set out to be heroic, as no true hero ever does. He had it forced upon him, and he was incredible.”

In Lessons for Dylan, he has a beautiful passage about death:

“I began charting the coincidences that had brought me, in the words of a Jewish prayer, to this season. I thought of the things I’d been able to do, the places I’d been able to see. My grandmother crossed the same river I was looking out at each day to work in a sweatshop, I’d been invited to the White House and met three Presidents — and hadn’t voted for any of them. If whoever had given this to me wanted to take it back, I decided, I could do it. I could give it back. And somehow knowing I was able to give life up gave me the strength to hold on. As for miracles, until I saw you being born, Dylan, I didn’t have a clue.”