“Well, in fact, I’d not read the book,” James Mason was saying, “but one could hardly be alive and employed in the acting profession and not know that ‘The Boys from Brazil’ had two stupendous leading roles in it. Oscar material. And of course, always trying to improve my position, I was hoping one of them would fall in my lap.”

He leaned forward to sip from his cup of tea, and then settled back onto the sofa, projecting a slightly rueful good humor.

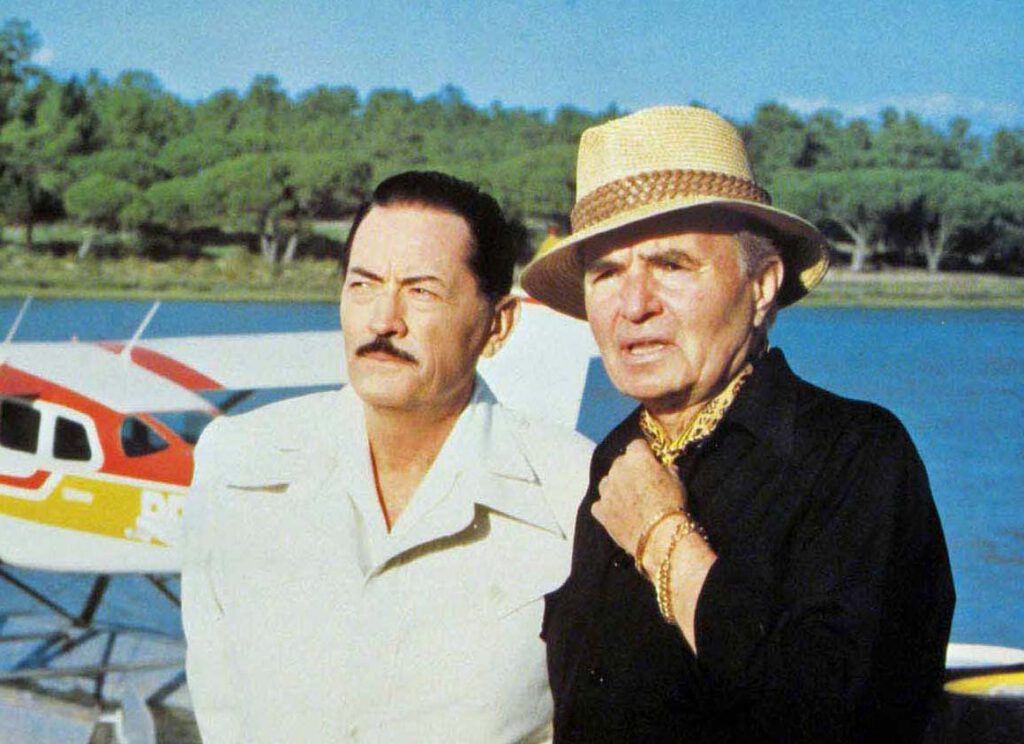

“The role of the Jewish investigator, of course, fell into Larry Olivier’s lap. I’d rather been hoping that Larry would be preoccupied with something on the stage, but no, he was free, and so that role fell in his lap. And then the other role, as Dr. Mengele, fell into Greg Peck’s lap. He’s been hot since ‘The Omen.’ So the upshot, of course, was that neither role fell in my lap.”

A sigh. “Two or three months passed, and then they called up and said they had a role for me after all. It was a supporting character, another Nazi down in Paraguay. They’d found that when Dr. Mengele was in Paraguay, he had no one to talk to, which made it rather difficult, of course, to develop character and suspense. So they fleshed out the other Nazi, and he fell into my lap.

“It was convenient, it was acceptable, I could even make sense of the character, and besides, it was four weeks work in Portugal, where I’d never been before.” He smiled. “When I arrived on the set in Lisbon,” he said, “I asked if Paraguay had pine trees. ‘It does now,’ I was told.”

Mason was in Chicago not only to promote “The Boys From Brazil,” but also for two other admirable reasons: “First, because at this point in my career I thought a little self-advertisement might be in order. And second, because I made the studio agree that if I came to Chicago, they’d let my wife and me fly on to New Orleans, where we plan to have a delightful time in several of the best restaurants.”

Mason seemed, at 69, to be not only in the prime of life but, most particularly, in the prime of James Mason. He projected civilization, manners, wit, the perfectly phrased understatement. “Look at these bookshelves with real books on them,” he said, conducting a short tour of his suite at the Whitehall. “I wonder if one is supposed to help oneself. Probably not. Perhaps so: They probably want to get these Winston Churchill books off their hands.”

He has been acting since 1931, is responsible for definitive performances in films like “Odd Man Out,” “The Man In Grey,” the 1954 “A Star is Born,” and as Humbert Humbert in Stanley Kubrick’s “Lolita.” He is also known for his villains, especially in “The Prisoner of Zenda,” “20,000 Leagues Under the Sea” and Hitchcock’s “North by Northwest.”

“That was the last time I was in Chicago, shooting ‘North by Northwest.’” He smiled at a memory. “Mr. Hitchcock was always very precise. There’s a scene in the picture where I’m supposed to be watching the landing of a plane that’s going to fly me across the Iron Curtain. Hitchcock told me to watch the plane land, wait until the pilot got out, count to three, and then make my move. ‘How would it be,’ I asked him, ‘if I moved at once?’ Hitchcock was unamused. ‘Oh, but you wouldn’t, James… you just wouldn’t’.”

Mason smiled again when I quoted from his entry in David Thompson’s “Biographical Dictionary of Film”: “He brings a unique sensuality to polite arrogance.”

“I’ll tell you a minor secret of playing villains,” he said. “Mine are usually polite and almost invariably charming. Nobody likes a nasty villain.”