hungry police reporters, and corrupt politicians, and an escaped murderer who spends half the film concealed in a rolltop desk in the press room. The play has been filmed twice before: In 1930 with Lee Tracy as the reporter and Adolphe Menjou as his managing editor, and again in 1940, when director Howard Hawks got the bright idea of making the reporter a girl (the new title was “His Girl Friday,” with Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant).

“This is not only the funniest comedy written during the decade of the 1920s,” Wilder declared, “but one of the best constructed comedies ever written. It is tight as a drum. We are making no, changes lightly. Every morning when we come on the set we say Hecht and MacArthur would have been proud of us.”

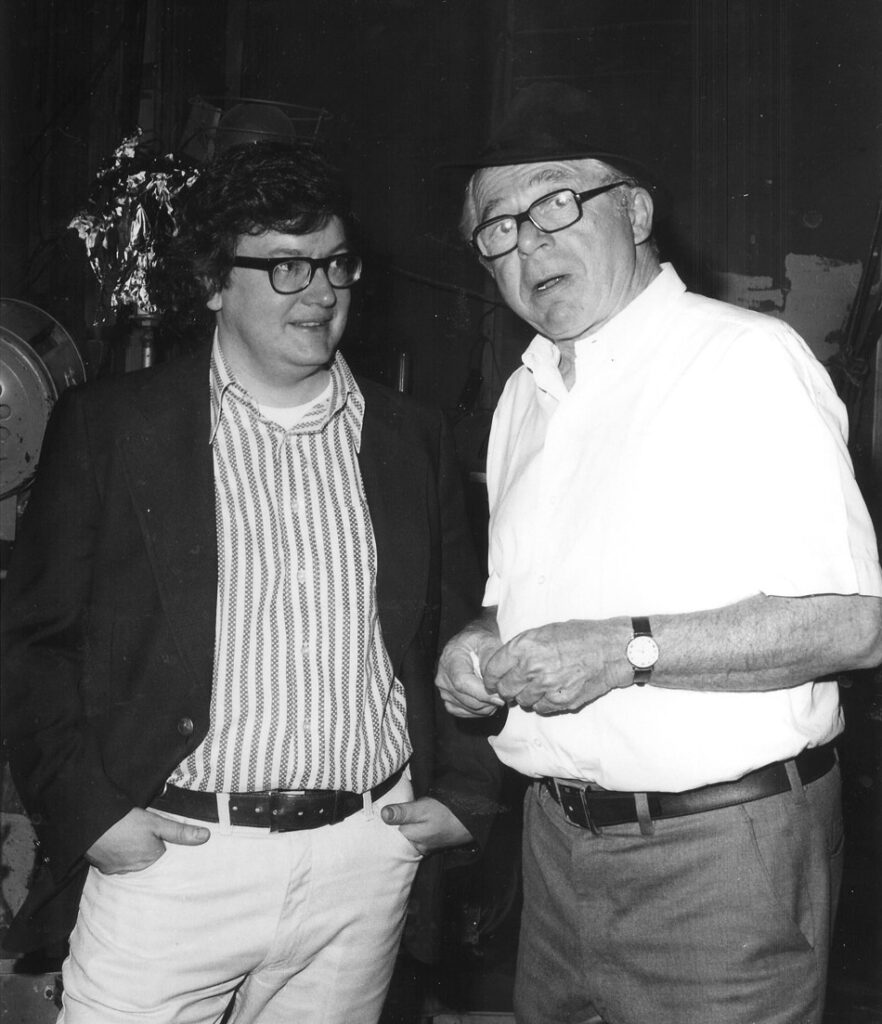

The movie marks the first time since “The Fortune Cookie” in 1966 that Wilder has been reunited with both of his favorite actors, Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau. Lemmon is playing Hildy Johnson, the quicktalking reporter, and Matthau is Walter Burns, his barracuda editor.

The play was inspired by experiences Hecht and MacArthur had as Chicago newsmen in the era around World War One, and most of the characters are based on real people who were thinly-disguised (if at all). Hildy was drawn from Hilding Johnson of the old Chicago Herald-Examiner, and Burns was a copy of Walter Howey, managing editor of the paper. The other reporters were also drawn from life, and so (the authors swore) was most of the dialog.

Wilder’s screenplay was written by his longtime collaborator and friend, I. A. L. Diamond, who’s as oft spoken as Wilder is outgoing. He stood nearby, also chewing gum, and observed gloomily: “The difference, I’m afraid, is that Billy is chewing to stop smoking, and I am chewing between cigarettes.”

Diamond said their film version would restore Chicago for the first time to its rightful status as the locale of the action. “People never notice it,” he said, “but in the first two film versions of ‘The Front Page,’ the city was never ever named. In this version, we’re restoring the original references to the Sheriff of Cook County, the Mayor of Chicago, the newspapers, and so on. And there won’t be any phony newspaper titles like the Chicago Globe. We’re using all the real names The Daily News, the Tribune and the real frontpage makeups.”

I asked Diamond what sorts of changes he’d made in preparing a screenplay from a comedy nearly 50 years old.

“Well, in the first place, it’s still set in the 1920s,” he said. “You couldn’t set it at the present moment because journalism isn’t like that anymore. In those days guys would do anything to get a story, and never more so than in Chicago. I wonder if the, Chicago reporters were more cynical because Chicago itself was more cynical and corrupt….

“Another thing you have to realize is that, even by the 1920s, things weren’t like ‘The Front Page.’ Hecht and MacArthur set it then, but their experiences were drawn from the circulation wars days around the First World War, when there probably wasn’t, a more violent and exciting newspaper town in the country. We’ve put in a few references to other big scoops of the period, like the New York Daily News photos of Ruth Judd in the electric chair, and the Leopold-Loeb case.

“But you have to be careful what you change, because the play’s basic structure is very sound. We changed mostly surface details that have dated now. But the guy hiding in the desk — that you can’t change. We eliminated some characters, added some new ones — we put in a young cub reporter, fresh out of school, just to emphasize the contempt the older guys felt for anyone who learned how to be a reporter by going to college. But the dialog, the pacing and the structure have been preserved.”

Especially the dialog and the pacing, Jack Lemmon was explaining a few minutes later, having been torn from both the movie’s poker game and a reallife backstage poker game. “When I talk about rapidfire dialog, what do I mean?” Lemmon asked. “I’ll tell you what I mean. With the average page of screenplay dialog, you figure on a rule of thumb of one minute per page. The other day we had two pages of dialog that took 45 seconds. That’s fast.

“With the way ‘The Front Page’ is put together, if you did it as a screenplay of ordinary length, you’d have a short subject. Everything moves like crazy. And it’s funny, it’s zany. You know, I’d never seen ‘The Front Page’ on the stage. I saw ‘His Girl Friday’ once, and I read the play in college. But in a way I’m glad I never saw it, because sometimes when you see the way another actor plays a role, you try so hard not to do the same things that you lean over backwards and are all wrong in the opposite direction.”

Lemmon said he and Matthau had been looking for a property for years, ever since “The Fortune Cookie.” They are close personal friends, and Lemmon directed Matthau in the 1970 movie, “Kotch,” which won him an Oscar nomination as best actor. Matthau didn’t win (Lemmon, of course, won this year for his dramatic role in “Save the Tiger”), and Lemmon speculated that maybe the voters of the Academy didn’t have enough respect for comic performances.

“Year after year, a dramatic performance gets, the, Oscar,” he said. “And yet comedy is harder to write, harder to direct and harder to act. The timing necessary in ‘The ‘Front Page’ is tremendously challenging to all of us. It’s a lot trickier than drama.”

Lemmon was called back for the next take, which required him to sit on the back of a chair and look supremely uninterested while everyone else in the press room screamed into their telephones about the escaped killer. He is uninterested because he has just told Walter Burns, in graphic detail, what he can do with his job, and how.

Among the actors playing the other reporters were suitably fasttalking types like Allen Garfield, who was a fight writer for the Newark StarNews before he got into acting, and Dick O'Neill, who had the title role in the Chicago production of Mike Royko’s “Boss,” and plays Buddy McHugh in the movie. “The first time somebody said, ‘What about the Mayor?’ I thought they were talking about me,” O’Neill confided).

Wilder, his hat pushed as always to the back of his head, stuffed in more gum and prepared to shoot. The set was in controlled chaos, and someone asked him how his fellow director from Austria, Otto Preminger, would have handled the scene. Wilder, who is as well known for being relaxed as Preminger is for exploding, smiled and told everyone a story.

“I saw Otto directing himself once,” Wilder said. “First there was a scene with another actor. Otto shot it 27 times until it satisfied him. The other actor was in collapse. Then it was time for Otto’s own scene. Otto stood in front of the camera. He said ‘Camera! Action!’ Then he said his line. Then he said, ‘Cut. Print. Excellent!’ Then he turned to the actor and said, ‘You see how easy?’ I think the guy could have committed murder….”

Now it was time to shoot. Wilder called for action. Lemmon sat on his chair back and nonchalantly exhaled cigar smoke into the thick air. The reporters raced to the windows. Searchlights searched and sirens screamed. The reporters raced back to their telephones and began shouting the good old standbys:

Give me city desk!

Stop the presses!

Tear up the front page!

“Cut,” said Wilder. He patted in his pockets for another stick of gum. “That was beautiful! That was terrific! That was nothing short of adequate!”