Far be it from me to make any grand assumptions about the

general character of the Venice Film Festival after spending all of two and a

half days here. On the other hand, he said, pulling up his khakis, ruffling his

backpack, and lighting a Marlboro, that’s what journalists do in the field: get

the lay of the land, gather the facts on the ground, and make a goddamn assessment. An assessment that’s square

and true and real.

Excuse me. Anyway, what I can glean here is that it’s a

relatively relaxed and well-organized festival, and a festival with an audience

that’s receptive to all manner of film, from restored classics to wildly

experimental features to conventional-for-what-it’s-worth international art

fare and more. Including, as is perhaps unavoidable, what we call Awards Season

Fare.

And so this morning I saw “The Danish Girl,” the new film

directed by Tom Hooper, who struck Oscar gold with his 2010 “The King’s

Speech,” starring Eddie Redmayne, who struck Oscar gold with his performance in

2014’s “The Theory of Everything,” and Uggi, the adorable dog who kind of

struck Oscar gold in 2011’s “The Artist.” Oh, wait a minute. The dog, owned by

the main characters in the film, is adorable and winsome but not Uggi. Why he

gets as much attention as he does in the movie is one of its mysteries; at one

point I was worried that the whole thing was gonna turn into a transgender

variant of “The Awful Truth.”

You see where this notice is going. Let me try and steer it

away from that place for a little while. “The Danish Girl,” scripted by Lucinda

Cox, based on an account of one of the 20th centuries first

medically-assisted transsexuals, is an engaging and picturesque film. It is

also, at this particular historical/cultural moment, a real problem picture in

the ideology/representation departments. As the transgender civil rights

movement gains cultural traction, the suspicion against trans stories told by

non-trans artists and performers is a roiling flashpoint (is that a mixed

metaphor?) in the, um, cultural conversation. While “The Danish Girl” is

scrupulous in its 21st-century Distinguished Film tastefulness—my,

the gorgeous cinematography, gee, the nuanced but nevertheless

heartstring-tugging Alexandre Desplat score— it is also largely free of special

pleading. Its signal virtue is in not treating Einar Wegener, Redmayne’s

character, as a Special Other, or in slavering Straight Person Compassion on

him or her. At its best moments it maintains a discreet detachment.

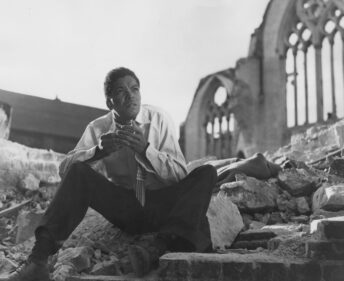

At the movie’s outset, Einar Wegener seems uniquely blessed.

He’s a landscape painter of great talent in 1920s Denmark, which looks here

like a great place to live. He has a gorgeous, kind, carnal, and talented wife,

Gerde, also a painter, albeit one whose career is lagging behind Einar’s. They

also have the aforementioned Jack Russell-esque dog, named Hvap. They have

nifty artiste pals, including a free-spirited dancer played by Amber Heard. No

kids yet, but “trying.”

One afternoon Einar visits the ballet, and in the costume

room gazes semi-longingly at the tulle. Later, Gerde asks Einar to wear ballet

shoes and stockings to help her out with a portrait she’s working on. And again

Einar gets that look on his face, and he gets it again looking at Gerde unlace

her boots. There’s a lot of this kind of indicating in the first third of the

film, and an uncharitable viewer might characterize some of the moments as

“Glen or Glenda” by way of “Masterpiece Theater.” The narrative picks up steam

after Gerde and Einar concoct a drag persona for Einar to disguise himself in

for an arts ball. There he beguiles a demimonde habitué played by Ben Whishaw;

complications ensue. Einar then adopts the persona of “Lili” over and over

again. In a “what incredible irony” moment, Gerde’s portraits of Lili set her

free as an artist, and launch her career. The marriage becomes strained as Lili

emerges as the more real person than Einar. And the movie really gains momentum

when it moves outside the world of the arts and into greater Early 20th

Century Europe, where transgenderism was practically unheard of, and

homosexuality categorized as a disease.

Einar’s relentless quest to become Lili is often met by life-threatening resistance, and Gerde, while not entirely comprehending, is

tireless in championing her husband as he insists on becoming not-her-husband.

Lili, in fact, can be a little callous to Gerde. (Her character is so

enlightened as to be contemporary. Remarking to one of her male portrait

subjects, she says, “It’s hard for a man to be looked at by a woman. For a man

to submit to a woman’s gaze is unsettling.” I’m sure that ideas along these

lines existed prior to Julie Kristeva, but to put them in the mouths of these

characters strikes me as too convenient. Anyway.) The ultimate irony of this

narrative is that it can be taken as yet another story of a man finding

him/her/self at the expense of his wife. Remember that old Dean Martin movie,

“How To Save Your Marriage And Ruin Your Life?” Switch the “ruin” and the

“save” and you’ve almost got this.

And as such, the movie winds up belonging, in the

performance respect, not to Redmayne but to Vikander. She’s stalwart, sexy,

funny, intelligent. I’m no Oscar prognosticator, but if “Ex Machina” is too

cerebral for the Academy (and I don’t know that it necessarily is), “The Danish

Girl” hasn’t that problem at all, and Vikander’s work here should earn her a

Best Actress nomination.

There. I’ve made an Oscar prediction. I feel so dirty.