Editor's note: Emma Myers is one of six recipients of the Sundance Institute's Roger Ebert Fellowship for Film Criticism for 2014. The scholarship meant she participated in the Indiewire | Sundance Institute Fellowship for Film Criticism, a workshop at the Sundance Film Festival for aspiring film critics started by Eric Kohn, the chief film critic and senior editor of Indiewire.

Honesty is a tricky thing. A delicate balancing act between truth, tact, and, above all else, trust, it becomes increasingly difficult the closer you get to another person. In documentary filmmaking, as in life, opting for flattery and avoiding controversy always seems to be the simplest solution, but Sundance's documentary category this year was populated by a striking number of personal portraits that refused to take the easy way out. Three films in particular—Steve James' "Life Itself", Jeff Radice's "No No: A Dockumentary" and Brian Knappenberger's "The Internet's Own Boy"—highlight the challenges. The three filmmakers took the time to discuss the challenges and responsibilities of representing a life onscreen, from conception to final edit.

For both Steve James' "Life Itself" and Jeff Radice's "No No: A Dockumentary", conception was inspired by written accounts of their subjects: the late film critic Roger Ebert and famed baseball player Dock Ellis, respectively. Facing the twin challenge of unearthing the man behind the myth, it was the books that convinced the filmmakers there was more to both these figures than their public images suggest.

Having produced the short "LSD a Go Go" (which played at Sundance in 2004), Radice was already familiar with the Ellis folklore—the Pittsburgh Pirates player famously pitched a no-hitter while tripping on LSD in June of 1970—but it was the book by poet laureate Donald Hall that persuaded him Ellis was deeper than just "that acid guy." "Without the Donald Hall biography," Radice explains over the phone, "I don't think I would've pursued it because I wouldn't have known so much about who Dock was as a human being."

Similarly, it was the candor and self-effacing humor Roger Ebert demonstrated in his memoir (also entitled "Life Itself") that convinced Steve James there was a film to be made. "With Roger there was always the risk of doing hagiography because he's so beloved and he's had such a great impact," the director offers over the phone from Chicago. "If I had read his memoir and it had been one of those memoirs where the person paints themselves in a completely flattering and heroic light, I don't know that I would've been interested in doing the film because I would've suspected that it would've been hard to do something true and three dimensional."

Ebert is the first to point out his own faults: "I was tactless, merciless, and egotistical," a voice-over reads from his memoir early on in the film. A lively group of talking heads comment on everything from Ebert's struggle with alcoholism to his penchant for "hired ladies" to his oft childish rivalry with TV cohost Gene Siskel. The myriad of interviews and archival footage James has compiled allow us to see Ebert the Pulitzer Prize winner, boy's club member, and finally, loving husband and adopted father and grandfather.

Ebert's tragic death midway through filming certainly shapes "Life Itself" in a way that was not part of the original conception—there is a particularly heart wrenching interview where Chaz describes her husband's peaceful passing—but James doesn't allow Ebert's death to overshadow his life. "I already felt like this was a significant project," the director says, "After his death I felt that weight and burden even more… it lent a greater gravity to our effort. People will certainly be able to make films about him going forward, but no one is going to be able to interview him…hopefully I do justice to him in this film." For James, "doing justice" is not about flattery, but rather honesty. Documentary filmmaking is ultimately a "collaborative undertaking," he says. "There's nothing that I left out in this particular case because I worried about how Roger or Chaz might react. Though that does happen—no documentary is candid on every single level, but I think that this one is right up there."

Beginning his project in earnest shortly after Dock Ellis passed away, Radice faced the additional challenge of doing right by his central subject without the benefit of a personal interview, relying instead on archival footage and interviews with old classmates, fellow ball players, and two remarkably composed ex-wives. The testimony of Ellis' second wife is particularly harrowing as she describes an episode of savage abuse she suffered at the hands of the man who was up until that point the absolute love of her life. It was a first and a last for both of them: she fled, and Dock went into recovery almost immediately. "I was surprised that she was so willing to share it," Radice said when asked about the difficulty of that interview. "All the people who were closest to him were all interested in a film that went beyond the LSD and covered the larger legacy of who [Dock] was. What I had to do was show them that I wasn't going for a salacious angle or surface level…that I was trying to go deeper."

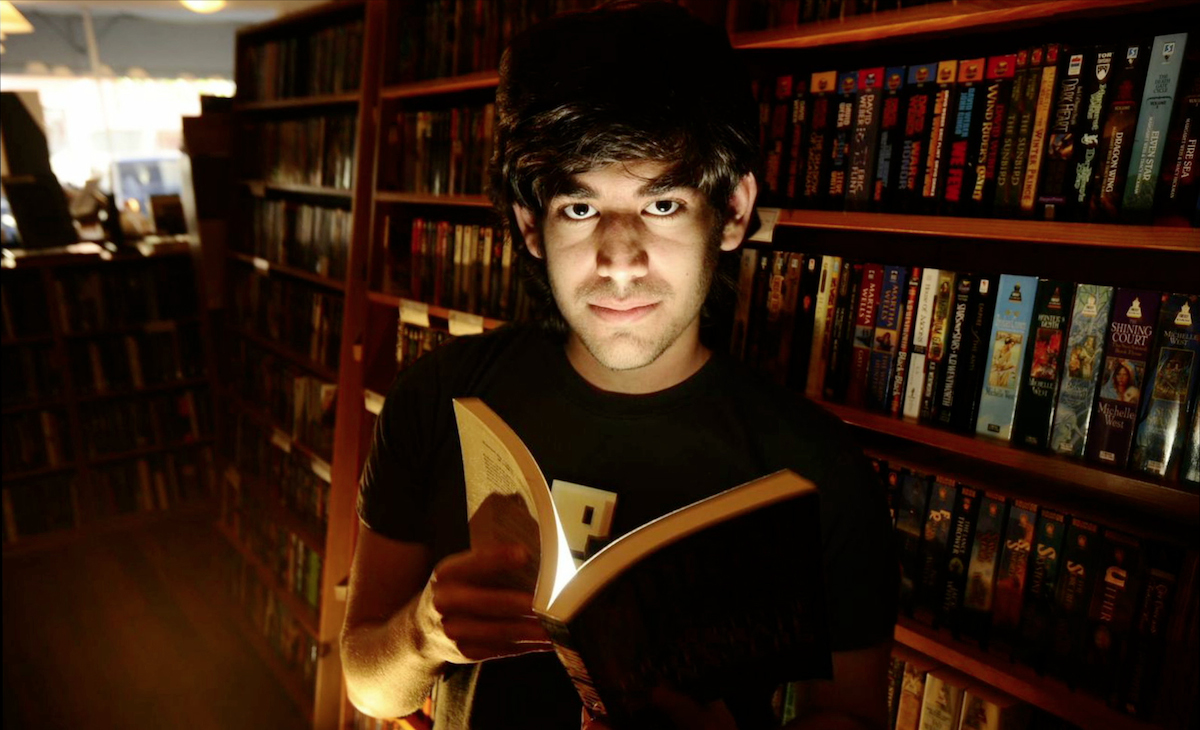

Brian Knappenberger's "The Internet's Own Boy: The Story of Aaron Swartz," treads on similarly sensitive territory. An elegy to the precocious computer genius who eschewed the riches of Silicon Valley in favor of crusading for the freedom of information, Knappenberger commenced filming just a week after his subjects' tragic suicide at the age of 26. In 2011, Swartz was arrested after mass downloading documents from JSTOR, an academic database with restricted access, via MIT's network. Instead of receiving what, at least according to the film, should've been a slap on the wrist, the young man was made an example of and charged with 11 violations of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. Facing a 35-year prison sentence and up to a million dollars in fines, Swartz killed himself before the trial ever got underway.

While "The Internet's Own Boy" is unashamedly in favor of Aaron from a legal standpoint, Knappenberger tries to show us all sides of the wunderkind as a person—even if the best insult his brother can think of is "twerp." If the picture seems a little too flattering, it's not because Knappenberger felt compelled to shape it that way. "We're all more complex people more than what can fit in an hour and a half," the director comments. "There was an attempt to get his story as accurate as possible. I didn't feel the need to amplify. He was a genius and also imperfect."

Striking a balance between loyalty to your subject and giving an audience what it wants to know becomes particularly hairy when grieving family members are involved. Knappenberger describes the process of getting close the Swartzes as an organic process: "I never felt restricted in any way. Maybe that's the short answer," the director says. "I started interviewing people and everybody seemed to decide that they wanted to open up to me. They were getting bombarded with questions from lots of people and requests for interviews and they were declining most of them. I think they understood that what I was trying to do something deeper." The only subject that was off limits for the family was the day of Aaron's death, "and I respected that," Knappenberger says.

For Radice that balance was more difficult to achieve. "The biggest challenge is what you leave out," the director reflects, "and I'm a little—I guess sensitive—to the reviews that go into that…The number one thing was that I did not go into Dock's children at all." Indeed, the question was raised in almost every Q&A. "These people are still alive, they have their own families. I think it would have opened up wounds that maybe haven't completely healed, and I just didn't think it was necessary for the story that I was telling to go there. I wanted to be respectful to his family and to his heirs."

All of the filmmakers emphasize the importance of sharing the almost-final product with the participating family members. "When you're building this kind of intimate relationship during the filming" Steve James explains, "its important to allow the main subjects to see the film before its done and hear them out on things that either they think you got wrong or shed light on things that are in there that you don't quite have. Sometimes its painful and sometimes its not, but in every case it's made the film better and in every case I think it's made the subjects of the film feel better about having participated in the film."

Though it may be painful, complex, strenuous and oftentimes ugly, honesty, it would appear, is always the best policy.