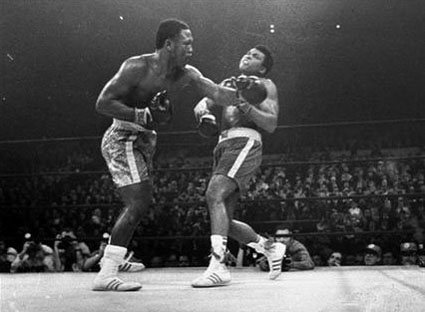

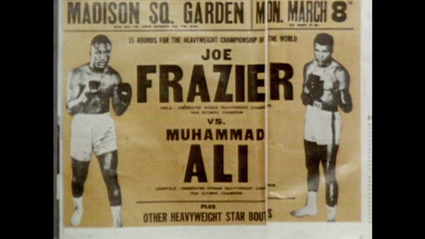

Joe Frazier was the toughest fighter I've ever seen. I keep a picture of him above my bed. It preserves, in one immortal monochrome moment, the most important punch Smokin' Joe ever threw: the left hook that floored Muhammad Ali, and retained Frazier's world title, in the final round of 1971's "Fight of the Century" in Madison Square Garden.

Joe Frazier was the toughest fighter I've ever seen. I keep a picture of him above my bed. It preserves, in one immortal monochrome moment, the most important punch Smokin' Joe ever threw: the left hook that floored Muhammad Ali, and retained Frazier's world title, in the final round of 1971's "Fight of the Century" in Madison Square Garden.

In the black space between the two fighters' bodies - Ali's crumpling in defeat, Frazier's stiffening with bloodlust - is scrawled a silver inscription: "To Scott, Get well soon, Joe Frazier". The signature is unexpectedly elaborate, the "J" turned into a playful loop, and the "o" and "e" written inside it. It is the signature of a man who was asked every day for his autograph and did not tire of giving it. The picture inspires me, not to get well from the chronic illnesses that afflict me - there is little hope of that - but to rage against the limitations they ostensibly impose.

In life, it was Frazier's perennial frustration to be seen as a secondary figure to Muhammad Ali, whom he at first admired, and then liked, and then came to despise and finally sought to destroy. Since Frazier's death, it has become even easier to lose sight of him in Ali's ever-lengthening shadow.

Cinema, certainly, has never showed a tenth of the interest in Frazier it shows in his greatest rival. Scores of documentaries and biopics tell the Muhammad Ali story but few of them mention Frazier any more than is absolutely crucial to the narrative arc. The best of these films is Leon Gast's "When We Were Kings," which chronicles Ali's 1974 title bout with George Foreman, the famed "Rumble in the Jungle".

Watching "When We Were Kings", the uninitiated viewer could easily believe that Ali never again fought in a fight of such significance. But he did. The following year he met Frazier in the third of their trilogy of matches, that most brilliant and brutal of heavyweight bouts, "The Thrilla in Manila". I am grateful that, a few years before Frazier died, the filmmaker John Dower made a quasi-sequel to "When We Were Kings", 2008's "Thrilla in Manila", in order to document that match. It is a fight worthy of dozen documentaries.

I watch Dower's film as I often as I can. I watch it because it does what documentaries ought to do: capture the characters and the events too awkward and too ugly to be smoothed out in fictionalized films. And I watch it because it is film's best record of a boxer who is as much a hero to me as Muhammad Ali.

Many of the onscreen roles in "Thrilla in Manila" are similar to those in "When We Were Kings". Among the talking heads, Ali's biographer, Thomas Hauser, plays the George Plimpton part, clearly documenting history while cleverly deconstructing legend. Opposite Hauser, Ali's fight doctor, Ferdie Pacheco, takes the Norman Mailer role as colour analyst. Frazier plays the role occupied by Ali in "When We Were Kings": the aging hero seeking to regain his championship. And Ali, for once, plays the villain, ridiculing Frazier, souring their friendship, enraging him by calling him an Uncle Tom.

Frazier was no Uncle Tom. His mother long feared he would never be able to "get along with the white folks" and "Thrilla in Manila" highlights something we often ignore when we spin the legend of Muhammad Ali: it was Frazier, not Ali, who had the more traditional black working class background. It was Frazier who grew up working in the fields. Ali famously began boxing because his bicycle was stolen and he wanted to be able to beat up the person who took it. Luxuries like bicycles were beyond poor black farmers like the Fraziers.

But Joe Frazier treated poverty like he treated pain: an inconvenience to be ignored, endured and overcome. As a child, Frazier fell and smashed his left arm. His parents could not afford to send little Joe, their twelfth child, to hospital, and so the arm healed as it was. Frazier could never fully straighten it again. As an adult, he would teach that crooked arm to deliver his left hook, for a time the most fabled blow in boxing.

At the 1964 Olympics, he broke his thumb in his semi-final but kept the injury a secret so he could compete again. He won the gold medal. Within a year, he suffered another accident, one that left him nearly blind in one eye and should have ended his professional aspirations. Again, he hid his injury, but this time he hid it not until the end of his next fight but until the end of his career. Joe Frazier made his living fighting the most fearsome men in the world - and half the time he couldn't see them coming.

When I developed a degenerative eye condition, and was told I might one day be blind, I was overcome by a surge of self-pity that was arrested only by the memory that, a few years after he became partially sighted, Joe Frazier became heavyweight champion of the world. I love my photograph of him: it reminds me that disadvantage can be beaten down by determination.

Frazier kept the same photograph on his wall. He kept it to remind himself of the moment when he realized he had won that match in Madison Square Garden, which was then, and perhaps still is now, the biggest fight in boxing history. He kept it, too, to remind himself of the night when the world shared his most fundamental belief: that he was better than Muhammad Ali.

But the photograph is not my favourite image of Frazier. That comes from a fight that ended far less gloriously for him, and cost him his status as the best boxer on Earth: his first fight with George Foreman. Frazier started fights slowly; Foreman finished them quickly. Two minutes into the opening round, the television commentator Howard Cosell yelled a phrase that still echoes in the ears of boxing fans: "Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!"

It was a shout of unalloyed surprise. Foreman, who was thought unbeatable after the fight, had been an underdog before it. The sight of him repeatedly felling Frazier, and doing it with contemptuous ease, was a shock the brain of a boxing aficionado could not properly process.

Cosell's cry sounded worst five seats away, where young Marvis Frazier, an apprentice boxer, was learning for the first time that his father was not invincible. At first, seeing his father stumble to the canvas again and again, he says he thought Daddy was playing. At last he realised he wasn't. Marvis can still recall the bout, and Cosell's commentary, second by second. In Dower's film, he acts it out, obviously enjoying an opportunity to perform a well-practiced Cossell impression on camera but just as obviously hating the memory of that awful fight.

Thirteen years after it took place, that awful fight had an awful sequel when Joe, horrified and helpless, watched Marvis being battered insensible by Mike Tyson, a fighter as ferocious as Foreman. When my dad and I debate boxing, we argue over which one of them had it worse: the son watching the father or the father watching the son. We usually agree it was the father, knowing precisely the pain his son was absorbing and, what's more, knowing that during his own career he could perhaps have withstood it and returned it to Tyson.

Joe Frazier versus George Foreman was an almighty mismatch. Foreman's body seemed designed to out-fight Frazier's. Frazier needed to be in close to throw his short hooks and stabbing uppercuts; Foreman was destructive from a distance. In one dreadful moment, Frazier, retreating for the only time in his life, turned his back to Foreman, and was floored by an awesome blow to the back of the head. Not since Sonny Liston unleashed his ungodly aggression on Floyd Patterson had sport's most fiercely contested title changed hands in so uneven a contest. Frazier and Foreman fought for five and a half minutes, and Frazier was knocked down six times.

And yet it is not the image of him being knocked down that best defines the fight or that best defines Joe Frazier: it is the image of him getting up. Each time he was forced to the canvas Frazier forced himself to his feet, unsteady but unyielding, moving forever forward, ready to punch and to be punched. There was no questioning look to his corner, no thought of surrender or attempt at crafty evasion, no instinct other than to raise his fists and resume the fight.

There will always be arguments over who in boxing's great history threw the best punches, but there should be no arguments over who was the best at taking punches, who had the deepest physical reserves, and the strongest psychological resolve, to charge unflinching into onslaughts that threatened to snap his neck or burst his kidneys. Joe Frazier could be knocked down but he was never knocked out. The KOs recorded against him, two by Foreman and one by Ali, are the most technical of technical knockouts. He seemed, through the frightening force of his will, to be able to override the body's instinct to retreat into unconsciousness when its limits of endurance are exceeded.

He could function in a state of pain beyond the reaches of other men who entered the ring and beyond the comprehension of men who never have. He would operate in that state for much of his last match with Ali. In "Thrilla in Manila", Frazier watches the fight for the first time. He's eager to see it, and coaches his younger self, calling out at the TV like an armchair pundit with a bet on the outcome. He's restless with yearning.

The temperature on that blistering Manila morning would have been especially insufferable for Joe, who hated heat and - in his sole concession to the indulgences fame can command - insisted on air conditioning wherever he lived or lodged. But that day Joe hardly felt the heat. While the introductions were announced, and Ali clowned with the trophy that would be awarded to the winner, Joe stood as if in a trance, coolly calculating the agonies he would inflict on Ali.

Ali would inflict equal agonies on him. By the thirteenth round, the eye that couldn't see was partly closed and the eye that could see was closed completely. Frazier had no warning that Ali's right hand was incoming until it detonated against his skull. In the fourteenth round, Ali realized this and sent that right hand, which had knocked out George Foreman, crashing into Joe's eye as often as he could summon the energy to throw it. It was his last gamble, his final effort, designed to finish the fight by knocking Frazier out. But the bell rang for the end of the round and Frazier still stood.

As Ali turned and traipsed to his corner, he was overwhelmed by exhaustion and, worse, by the dreadful realization he had hidden from for four years and across the 41 rounds of his three fights with Frazier: that he, the great Ali, who could punch more quickly and more accurately than anyone alive, could not knock Joe off his feet even when Joe was all but blind. Ali's courage evaporated and he asked for his gloves to be cut from his fists.

Consider for a second the courage of Joe Frazier who, staggering sightlessly to his stool, did not think of conceding. Exhausted and immobile, his face freakishly swollen from the hideous assault he had suffered, he insisted on being allowed to go back out to face the greatest boxer any of us have ever seen, without being able to see him. As Frazier sat in his corner demanding his trainer allow him to continue, Ali sat in the opposite corner demanding his trainer allow him to withdraw. But, in the sourest irony any fighter ever had to swallow, the man who wanted to carry on lost to the man who wanted to quit.

Frazier's cornerman, Eddie Futch - who trained four of the five fighters who beat Ali - had seen a man die in the ring before and hadn't the stomach to see it again. While Ali's cornerman, Angelo Dundee, was trying to persuade his charge to prolong the fight by one last round, Futch persuaded the referee to stop it. Hearing the news, Ali stood to celebrate - and immediately collapsed.

Ali's famed description of the match in Manila - "the closest thing to death without dying" - reveals something not just about the infernal intensity of the fight, but about each fighter's attitude to it. For Ali, as for all reasonable men, dying was the worst possible outcome of a fight. For Frazier it was not: he would have preferred death to defeat. Such claims are often made of other boxers - particularly in obituaries and biopics - but seldom, if ever, are they accurate.

Joe Frazier was a true fighter and a true fighter is as rare a true genius. This is what those who seek to sanitize and sissify boxing will never understand: it is better for a man like Frazier to die having won the heavyweight championship of the world than to live forever without it. The film shies away from endorsing this sentiment but it shows us several people who do. Among them is Frazier's girlfriend of the time, who we might expect to have wanted the fight stopped, but who is adamant it should have continued. She regrets that un-fought fifteenth round as keenly as Frazier.

The cosmic injustice dealt him in Manila never left Frazier's mind and twisted his character. It is true that, for decades, his hatred of Ali - fuelled by all Ali's unforgiven insults - darkened Joe's spirit. But that was only a symptom of the eternal bitterness that had infected him the instant he was not allowed out for that final round.

We do not like our fighters to retain the characteristics of fighters once they retire. For us to welcome them as celebrities, and elder statesmen of sport, we demand they snuff out the meanness and unseemly stubbornness that first earned our attention. Foreman and Ali could do this. That is why Foreman, with his self-effacing affability, counts his wealth in hundreds of millions of dollars. And it is why Ali, who has replaced his position as America's agitator extraordinaire with a role as a prophet and peacemaker, remained the most famous man of the 20th Century.

Frazier could not do this and had no desire to - and that is why he lived his last years in a room at the back of a boxing gym in the area of Philadelphia known un-ironically as "The Badlands". It is this forlorn gym in Philadelphia, not the bright ring in Manila, that is the most evocative location in Dower's documentary. It becomes emblematic of Frazier: like his body, it looks decrepit but stands defiant, apparently only functioning because Frazier insists it will.

It is both sad and inspiring to see Frazier as he is at the end of "Thrilla in Manila". He is aged 63 but looks 83. He is wearing his old ring robe and has his fists taped. He adopts a rickety stance and slowly shadowboxes before arthritically working the speed bag. As the film fades out, Frazier is still throwing punches.

In autumn 2011, newspapers announced that Frazier's greatest fight would be against the vicious and virulent cancer that had been discovered in his liver. A few days later they reported his death. I dislike the phrase "the fight against cancer", with its asinine implication that those cancer kills are in some way losers who could have survived if only they had shown sufficient guts and guile. If it were possible to simply fight cancer, Joe Frazier would have knocked it cold - because Joe Frazier was a fighter, first and always. And he was the toughest fighter I've ever seen.

Scott Jordan Harris is a British film critic and sportswriter. He is editor of the books World Film Locations: New York and World Film Locations: New Orleans. He is on Twitter as @ScottFilmCritic.

Scott Jordan Harris is a film critic from Great Britain. Formerly editor of The Spectator's arts blog and The Big Picture magazine, he is now a culture blogger for The Daily Telegraph; a contributor to BBC Radio 4's The Film Programme and Front Row.