The original Italian title of Mario Bava’s 1964 “Blood and

Black Lace” is “Sei donne per l’assassino,” that is, “Six Women For The

Murderer.” It’s certainly not the first work in cinema and literature to

concern itself with the serial murder of women, but the upfront nature of the

title and then, of course, of the film’s actual content suggests a border

crossing of sorts. Not only did Bava’s film help codify the exploitation genre

referred to by buffs as “giallo,” it also influenced John Carpenter’s

“Halloween” and by extension a host of body-count and final-girl horror movies,

not to mention the ostensibly convention-overturning pastiches and travesties

that were the “Scream” movies (soon to be an MTV series, I learned recently,

unless it’s come and gone already).

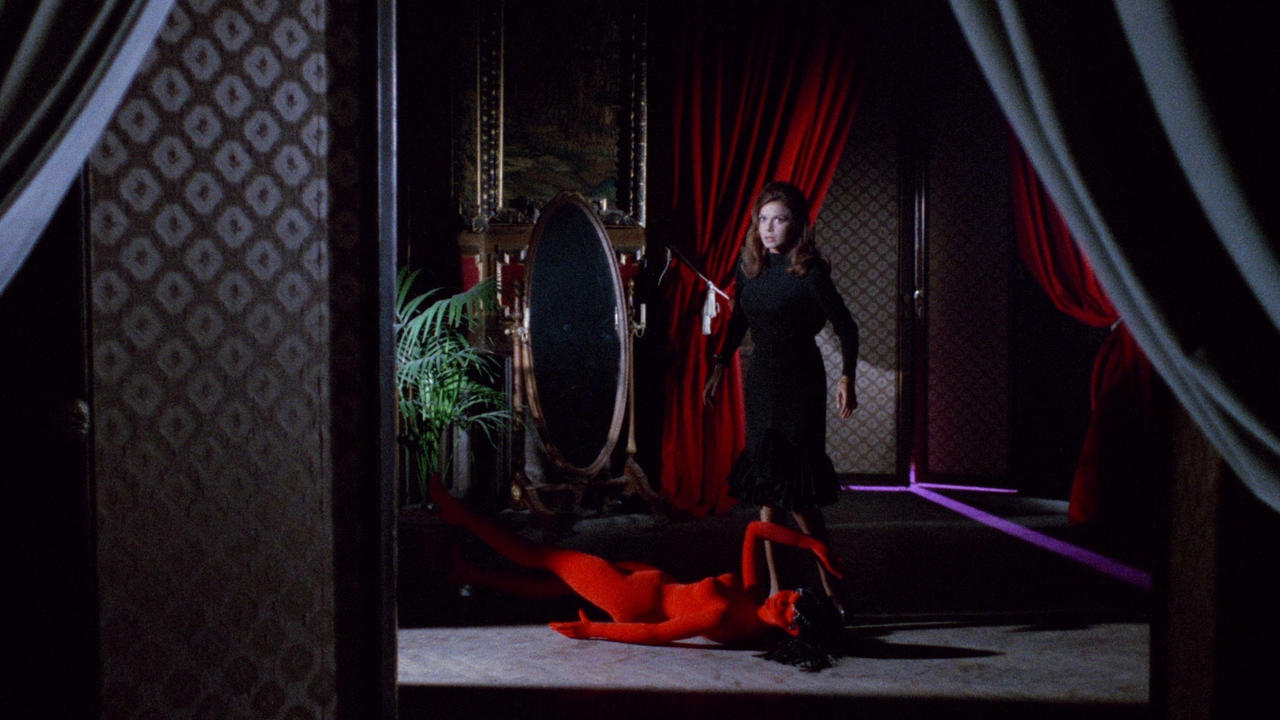

It’s generally a given that the sexual politics of such

movies are either hopelessly retrograde or, in some individual cases,

overturned to such extremes as to be transmuted into something radical. In any

case, the spectacle of beautiful women meeting death in grisly ways has only

a very few meanings behind it, none of them wholesome. Watching “Blood and

Black Lace” in a gorgeous, eye-popping restoration now on Blu-ray disc courtesy

of the Arrow label, the visual quality of the film often overwhelms all other

considerations. Bava was a master of in-camera illusions, dazzling lighting

effects, and color, and he orchestrates his sequences of death like a stage

magician walking through an especially elaborate trick. The victims of the

murders, all associates of a fashion house, are all women, and all beautiful,

and many of them are in effect killed twice, first drained of life by an

impassive, trenchcoat-clad, faceless killer, then mutilated and laid out for

display and discovery by a surviving friend and associate.

For all that Bava’s poetic morbidity attempts to do an end

run around the idea of misogyny, rather than face up to it. The murders are

investigated, of course, and people say things like “We’re dealing with a mad

man here,” and “Or a homicidal sex maniac” despite the fact that the victims

have not been sexually brutalized. It’s hardly a surprise that by the end it’s

revealed that the murders have greed as the motive, that the killers are wholly

“rational” actors trying to throw attention away from a money-grabbing scheme

by wiping out actors who pose a threat via an invented lunatic straw-person.

With such banal whys and wherefores, the film’s murder

scenes act as Rorschach tests for the viewer, albeit one especially crafted for

the male gaze: how close together do you like your Eros and Thanatos? With

Hitchcock, the sexual obsession, particularly as expressed in “Vertigo,” is

that of absolute possession, from beyond and leading back to the grave. For

Bava, who frequently populates his murder scenes with simulations of the human

form (body-fitting torture instruments in “Black Sunday,” model mannequins in

“Blood And Black Lace” and even more so in the later “Lisa And The Devil”) the

preoccupations are with beauty and its desecration, either by nature (old age

and rot) or violence. These concerns don’t transcend politics/ideology, but

they stem from a long tradition in Western art that doesn’t necessarily warrant

being written off as merely misogynist. This is not to suggest that a

contemporary viewer of the movie ought to be gleefully guilt-free, or unmindful

of the film’s implications. But the spell it means to cast is rooted in

concerns so old it’s easy to mistake them as almost elemental. Nevertheless,

for all its visual beauty, Bava’s baroque vision here doesn’t display any will

to subversion. He’s here an inspired, maybe genius, craftsman who’s content to

draw within the old lines. But it’s interesting to look at the range of

variation that exists within what a lot of people are willing to lump within

the same exploitation cinema parameters. In the next part of this

consideration, I’ll look at the Blu-ray release of an adaptation of an old

horror trope that’s a truly off-kilter radical imagining.