The seats in the big Grand Theatre Lumiere and the Debussy in the Festival Palais are cushy, velvety, and wide, but the rows are close together. A recent renovation in the Lumiere has resulted in even more luxurious seats, but reduced the legroom to a distance that would do a budget airline proud. There is now almost no way, emphasis on almost, for new arrivals to move into a row without waiting for everyone to stand up. Still, many try to charge right in. Do they ever.

While waiting for the 8:30 am press screening to begin this morning, a few of us began to discuss appropriate ways to deter butt-in-the-face syndrome. I vote for sharp little cocktail forks, which could easily be hidden and deployed on the targeted butt as needed. The brand-savvy Vogue critic suggested that the festival logo be stamped on the offending parts. A Parisian suggested the low-tech solution of a hard pinch.

Primed for meanness, we were in fine fettle to mock one of the festival’s most irritating competition offerings so far, “Mon Roi” by Maiwenn, whose previous film “Polisse” won the Cannes Jury Prize in 2011. There’s no official English title, but the literal translation of “Mon Roi” is “My King.” Like “Polisse,” the film stars Emmanuelle Bercot as the female lead. Bercot is here in Cannes in more than one capacity, since she also directed the opening night film “Standing Tall.” This is a film designed around big, showy star performances, especially by male lead Vincent Cassell (“Black Swan,”) who is also here in Cannes with Matteo Garrone’s “Tale of Tales.”

At more than two hours in length, “Mon Roi” covers ten years in the tumultuous on-and-off-again relationship of Tony (Bercot), (the name is short for Marie-Antoinette), and Georgio (Cassell), a charmingly mercurial ladies’ man whom she first hits on in a club. The story unfolds largely in flashback through Tony’s memories as she languishes for six weeks in a rehab facility following a serious but implied on-purpose skiing accident.

There’s an almost mathematical quality to the way the two narrative strains of the film are regularly alternated. There are lengthy rehab sequences, which fall into what I am starting to label “social services cinema.” This is a tedious genre peculiar to the French, in which some aspect of the medical, social, or legal support systems are detailed at length within the context of fiction. “Standing Tall” and “Mon Roi” are just two examples. I now know a lot about physical therapy in France. The other side of “Mon Roi” is based in the stereotypical movie fantasy in which everyone lives in a fabulous apartment, has great clothes and walk-in closets, and never, ever has to go to work.

Tony and Georgio meet cute and unconventional and their love affair is a rollercoaster from the start, with highs involving so much maniacal laughter, practical joking and horseplay that the plot falls into a wearying sameness. The lows are no less vocal, but the histrionics involve fits over Georgio’s lingering attachment to a suicidal model, other miscellaneous lapses, and his drug and alcohol addictions. Nevertheless, Tony is supposed to be the sick one, popping sedatives for depression. “I want a baby from you: with your eyes, your face, your crappy moods,” proposes her enthralled husband-to-be.

“Stand by your man” is the point director Maiwenn appears to be making as she plods toward the conclusion with a sequence of lingering/loving close-ups of Georgio’s rugged face from Tony’s point of view as they sit in a parent-teacher conference. I don’t know what the guy who was angrily shouting at the screen in French was saying as the credits rolled, but I have a feeling he got it just right.

Star-crossed love against a background of war and ethnic hatred is the subject of “Zvizdan,” playing in Un Certain Regard today. Onstage to introduce the film and his cast and crew, Croatian director Dalibor Matanic said, “Wherever you live in the world, life is too short to waste it on hatred. This is our way to fight for love.”

Matanic presents three stories set in and around two neighboring Balkan villages in three different decades, and each involving forbidden love between a Croatian man and a Serbian woman. He very effectively uses the same actors in the leading roles in all three, although the eras, names, and circumstances change.

War, hatred of “them,” however they are defined, and ethnic cleansing drive the outcome of these stories, but we never see the actual conflict of war. Matanic instead underlines the perpetual sameness of late summer in a sleepy setting of rolling foothills, high grasses, buzzing insects, and a sparkling lake, where the young of each generation hang out. What changes in small increments is the halting and painful progress toward rapprochement as it is worked between individual men and women.

The cast is made up of neophyte actors in solid performances, especially Goran Markovic, who plays the male lead in all three sequences. The innocently joyful pairing in 1991, of Ivan and Jelena, a couple planning to run off to the big city together, ends in an altercation at a makeshift roadblock between villages, and with Jelena wailing in grief over his dead body.

In the film’s most complex and subtle sequence, a Serbian mother and daughter return to their ravaged stone farmhouse in 2001 to begin life anew. Grief over the death of her son in the ethnic conflict doesn’t prevent the mother from hiring Ante, a shy but amiable Croatian carpenter, or from understanding in her heart that bridging the gap with “them” is the only way forward. Sexual tension builds between the two young people, and finding herself at a crossroads, the daughter chooses hate.

Forward to 2011, and Luka drops in on his parent after a long absence. His unplanned visit to the Serbian woman he abandoned after fathering her child is less welcome. The film poses the choice between holding onto the past or wiping the slate clean.

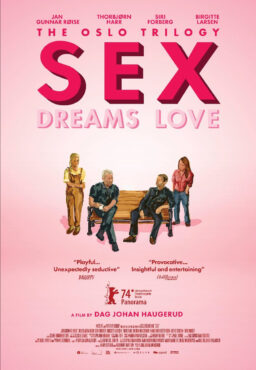

Norwegian director Joachim Trier scored a spot in competition with “Louder Than Bombs,” his first film in English, which features Isabelle Huppert, Gabriel Byrne, Jesse Eisenberg, and Devin Druid. His 2011 film “Oslo, August 31” brought him considerable exposure at international festivals including Cannes, and he’s considered a rising star.

There’s an image in “Louder Than Bombs” of Huppert lying prone and floating in mid-air. The plot of the film is a lot like that, in that it floats chunks of information and the beginnings of multiple storylines and leaves them unattached. Deliberate as this may be, the strategy gives the film a tentative, rough draft quality that generated a lukewarm reaction at tonight’s press screening.

Huppert is seen only in flashback in the dreams and imaginings of her husband Gene (Byrne), and her two sons, Jonah (Eisenberg), and Conrad (Druid). Dead three years, she was a world-famous war photographer who spent months at a time away from her family. The curator of a new exhibition of her work confides to Gene that he feels obliged to make public the fact that Isabelle’s death in a car wreck was suicide, information Gene and his eldest son know, but which was concealed from the younger son.

At this point, Isabelle becomes more of a catalyst for the story rather than the story itself. Trier takes off in several directions to fashion a father-son showdown that is also a tender coming-of-age film and a guilt trip that centers on the secrets that each family member holds close. Trier employs voiceovers of the inner thoughts of his key characters, slow motion, abrupt blackouts, and fantasy sequences to convey the many levels of awareness.

Sometimes this combination works, and sometimes it doesn’t. There’s a dead end aspect to subplots involving infidelity, lies, implied sinister online activities, and first love, and it stands in the way of a clear direction. Huppert and her secrets ultimately seem like mere props in a film that can’t decide what it wants to be.