Adolph Hitler’s bodyguard, Rochus Misch, died last week. If it’s true that he rarely left his beloved boss’ side, as he told interviewers, then it’s likely he saw a lot of movies.

According to a new book, Hitler was quite the film buff. Hugh Hefner’s legendary weekly classic movie nights have nothing on the Führer’s viewing regimen. Hitler screened a film every night before going to bed. He picked the titles himself. He loved American films. He was partial to the comedy team of Laurel and Hardy and to Mickey Mouse cartoons. He was a big fan of Greta Garbo.

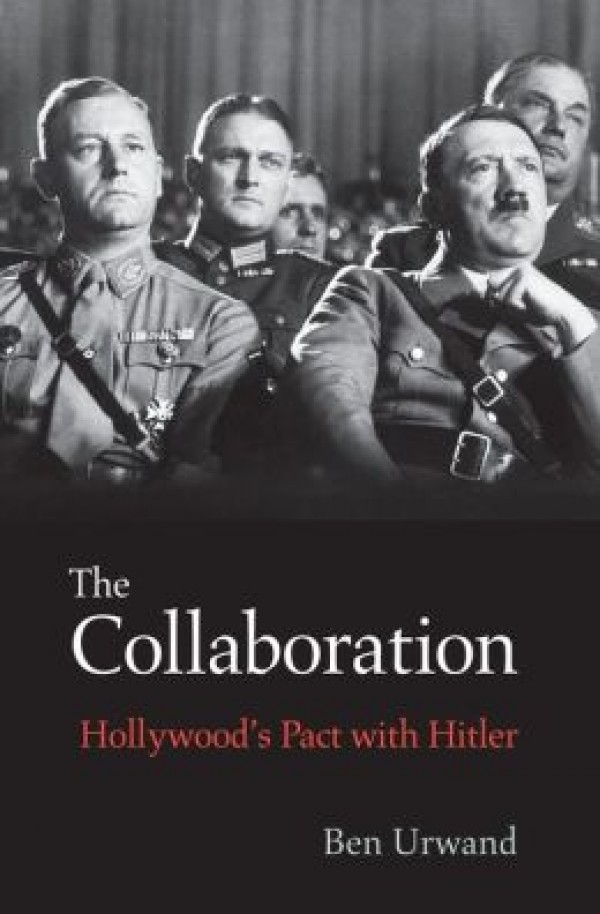

But according to “The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler” by Ben Urwand (Harvard University Press), not all American films passed muster with Hitler and his cohorts, and they used their position to exert influence on Hollywood studio heads (Jewish Hollywood studio heads) who acquiesced to demands that offending dialogue or scenes be censored. In extreme cases, films in development deemed to be detrimental to the image of the Third Reich were cancelled.

Urwand’s controversial book challenges conventional wisdom about Hollywood’s role in the war effort, “namely that Hollywood was synonymous with anti-fascism during its golden age,” the author writes. Hollywood’s defenders can point to the studios’ prodigious and prolific output during these years, from Nazi spoofs and satires (The Three Stooges’ “You Natzy Spy,” Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator“) and propagandistic documentaries (Frank Capra’s “Why We Fight” series) to espionage thrillers (“Confessions of a Nazi Spy”), and morale builders (“Casablanca,” “To Be or Not to Be”). Even cartoon characters were recruited. Donald Duck has a Nazi nightmare in the Oscar-winning “Der Fuehrer’s Face,” Daffy Duck withstands the seductions of ‘Hata Mari’ in “Plane Daffy,” and one of the Three Little Pigs defends his home with American defense in Tex Avery’s “Blitz Wolf.”

But these were mostly produced in the 1940s. The 1930s, Urwand contends, were a different story, as the studios sought arrangements with the German government to protect their investment in that country as a once-vital market for their films.

Urwand is a native Australian and a self-professed film lover who grew up watching black and white Hollywood films from the 1940s. “I would say before I began this project (nine years ago), Hollywood movies from this golden age were the ones I’d been obsessed with my teenage and adult life. I was familiar with the anti-Nazi films. I was surprised when I started to discover the things I found in the archives.

The trigger for the book, Urwand said in a phone interview, was a comment screenwriter and “What Makes Sammy Run?” author Budd Schulberg offered in the documentary, “The Tramp and the Dictator.” In the 1930s, Schulberg said, Louis B. Mayer, the head of MGM, screened films for the German consul in Los Angeles and made changes to those films based on his objections.

“I was aware Hollywood wasn’t engaged in attacking the Nazis in the 1930s,” Urwand said. “That came later. This could be a plausible explanation for why: they were screening their films for real Nazis in Los Angeles.”

But what really set the book in motion, Urwand said, was a letter to Hitler that he found in a Berlin archive. It was a fawning letter soliciting Hitler’s opinions on American films that signed off, “Heil Hitler.” It was on Twentieth Century Fox stationary. “On this single page, you have one of the biggest studios implicated in dealing with the Nazis,” Urwand said. “I wasn’t prepared to believe it until I saw this document.”

Hitler loved 99 percent of Hollywood movies, Urwand said. Whereas Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel would have their “thumbs-up/thumb down,” Hitler boiled down his movie reviews to three basic categories: good, bad, and “switched off by order of the Führer,” (Ernst Lubitch’s “Blackbeard’s Eighth Wife” suffered this fate, while “Tarzan” was simply deemed “bad”).

“There were a tiny percentage of cultural products that he considered to be incredibly dangerous,” Urwand said. “These were films that he considered to be propagandistic against Germany and his movement.”

The Nazis took dramatic action against such films. The release in Germany of Lewis Milestone’s antiwar classic, “All Quiet on the Western Front” on Dec. 5, 1930, was a “critical” event, Urwand said. “This is the moment when the Nazis were really rising in Germany.”

The film, with its brutal depiction of war and of idealistic, gung-ho German students turned into psyche-scarred war veterans sparked riots in Germany and the film was subsequently banned. Carl Laemmle, the president of Universal Pictures, which released the film, was a German native and wanted the film shown there. In August 1931, he submitted a heavily edited version of the film for approval. The German Foreign Office agreed to this new version under one condition: this version would be substituted in the rest of the world.

In his book, Urwand writes, “The Nazis actions…set off a chain of events that lasted over a decade. Not only Universal Pictures but also all the Hollywood studios started making deep concessions to the German government, and when Hitler came to power in January 1933, the studios dealt with his representatives directly.”

Warner Bros., the studio that would later produce “Casablanca,” was the first studio to screen films for Nazi officials at its headquarters, Urwand writes. Jack Warner ordered that the word “Jew” be excised from the 1937 film “The Life of Emile Zola.”

The German market for Hollywood films in the 1930s was dwindling and as the decade progressed, the Nazis imposed restrictions on the studios, Urwand said. “It was striking to me that Paramount in 1936 had a net loss in Germany of almost $600. So why are they working so hard to keep this market that is financially very minor? Why didn’t they just leave? The reason is they’d been there for decades and they saw the German market as significant. The German people loved Hollywood movies. Even as the German censors were clamping down over the course of the 1930s, they were extremely popular. The studios didn’t want to abandon an investment that might again come back. They were also concerned that if Hitler started a war and occupied other territories, they would not just lose the German market, but others as well.”

The story Urwand tells is not without heroes. He cites screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, who, in 1933, wrote “The Mad Dog of Europe,” which, had it been produced, would have been the first film to address Hitler’s persecution of the Jews. But no studio would touch it for fear of it threatening business relations with Germany. “We have terrific income in Germany, and as far as I am concerned, the picture will never be made,” Urwand quotes MGM’s Louis B. Mayer.

“Mankiewicz saw what was going to happen (in Germany) within a few months of Hitler coming to power,” Urwand said. “If you want to see how much people actually knew about Hitler at the time, look at that script.”

(Three years later, MGM also cancelled production of “It Can’t Happen Here,” based on Sinclair Lewis’ anti-fascist cautionary tale about a United States senator who is elected president and establishes totalitarian rule).

Another hero is legendary Chicago newspaperman turned playwright and screenwriter Ben Hecht, who in the 1940s “did exactly what the studios did not do,” Urwand said. A radicalized Jew, the author of “The Front Page” and the original “Scarface” took out full-page advertisements in the newspapers to raise awareness about the genocide in Germany.

Among these was the poem, “Ballad of the Doomed Jews of Europe,” in which he tells the “Four million Jews waiting for death” to “Don’t be bothersome; save your breath/The world is busy with other news.”

Much of the controversy surrounding Urwand’s book is focused on its title, specifically the word “collaboration.” Perhaps the book’s most outspoken critic, Thomas P. Doherty, a historian and author of the book, “Hollywood and Hitler: 1933-1939,” contends that while Hollywood executives may be guilty of greed, that is not on par with the actions of the Vichy government. Alicia Mayer, whose great-uncle was Louis B. Mayer, wrote a scathing rebuttal to the book on the Hollywood Essays website (“How could my family be accused of not just tailoring films to eliminate all traces of ‘Jewishness’ for Nazi-led Germany, but actually working with them to peddle their terror and hate?”)

Urwand’s response is simple: “The reason I used that word is because that’s the word they used. The job of the historian is to understand the past on its own terms. Time after time I found that word in original documents in Germany and the United States. If this is the word that both parties used to describe their relationship over the course of an entire decade, that is the word I should use. I did not impose it on the material.”

Urwand insists he is not someone “who is out to bash Hollywood. But I would stress that this was a particularly dark period in Hollywood’s history and it’s important to face the reality of these dealings and all of the findings.”