Alex was born with both male and female sex organs. Although “reassignment” surgery was considered after birth, she has lived as a woman until the age of 15, when “XXY” takes up the story. She uses hormones to subdue her male characteristics, but now she has become unsure how she really feels. Alex is neither a man in a woman’s body, nor a woman in a man’s body, but both, in the body of a high-spirited tomboy who broods privately in uncertainty and confusion.

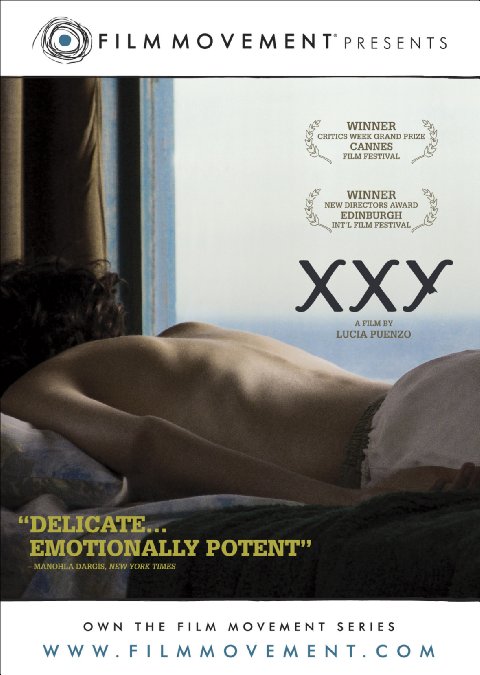

Hermaphrodite is no longer the P.C. term for such people, who prefer “intersex,” although it seems to me that they are not so much between the sexes as encompassing both of them. Their stories are often exploited in lurid, sensationalistic accounts. Lucia Puenzo’s “XXY” is the first film that I’ve seen on the subject that is honest and sensitive — indeed, the only one. It is not a message picture, never lectures, contains partial nudity but avoids explicit images and grows into a poignant human drama. It will be described in terms of Alex’s sexual ambiguity, but that would simplify it, and this is not a simple film but a subtle and observant one. (“XXY” won the top prize in Critics’ Week at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival.

Alex (Ines Efron) is the child of a Marine biologist named Kraken (Ricardo Darin) and his wife, Suli (Valeria Bertuccelli). They have moved their family from Argentina to an island off the shore of Uruguay, where Kraken can study specimens and Alex can grow up more privately. That has not been easy. “I’m sick of doctors and changing schools,” she tells her mother. Since other kids somehow sense something strange about her, she cannot easily keep her secret. Recently she has stopped taking hormones. Perhaps (Alex never says) it will be easier to account for a penis if she does not live as a girl.

Guests arrive on the island: A plastic surgeon named Ramiro (German Palacios), his wife, Erika (Carolina Peleritti), and their son, Alvaro (Martin Piroyanski), who’s about Alex’s age. Suli has invited them so the doctor can “get to know” Alex and tells her husband she has not told them about their child’s secret. Alex and Alvaro are attracted to each other, and together have what is possibly the first sexual experience for either. This is shown with great dramatic impact, but not with graphic intimacy; the point is not what they do, but how they feel about it.

The film gives full weight to all of the characters. When Kraken first saw his newborn infant, “I thought she was perfect.” He wants to give Alex the right to make her own decision about having surgery. His wife thinks Alex’s penis should be removed, but is not shrill or insistent. Both in their different ways love and care for their child.

In contrast, the surgeon is brutally cruel in a conversation with his own son, who may possibly be starting to realize he is gay and may be attracted to the androgynous Alex for that reason. Alex and Alvaro sense some sort of unstated, even unconscious, common bond. Meanwhile, there are problems on the island. Alex has broken the nose of her boyfriend, possibly (I’m not sure) because he wanted to explore her body. And local teenagers chase Alex on the beach and pin her down to settle the mystery of her physiology.

I am making the film sound too melodramatic. The shots are beautifully composed, the editing paces the process of self-discovery, the dialogue is spare and heartfelt, the performances are deeply human — especially by Efron, who I learn was 22 when the film was made, but never looks it.

Nor does she look too distractingly male or female, and so is convincing as both. The film accumulates its force through many small moments and some larger ones. It assembles its story as a careful novelist might, out of many precise, significant brushstrokes. And Efron finds a sure line through the pitfalls of her role, succeeding in playing not girl or boy, but — Alex.

We understand that Alex is in despair, and we see it reflected in a sketchbook she has drawn. She is weary of being poked and prodded by the unhealthy curiosity of society, weary of being considered a freak. Alex wants to be accepted as herself but is not sure who that is. In wanting her to find happiness, her parents provide a refuge, even though they hardly even discuss her intersexuality with her in so many words. And finally that’s why this film can avoid a “solution” and yet end with a bittersweet glow.