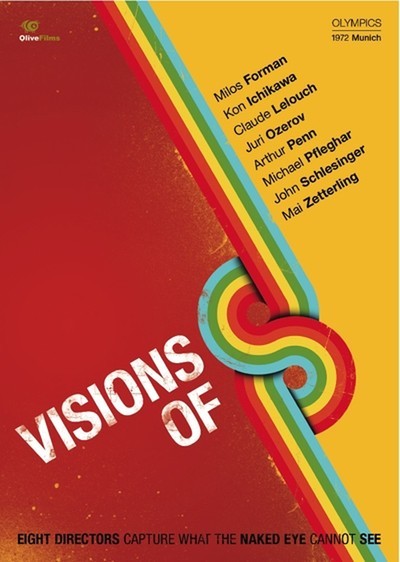

The idea sounded like a great one at the time: Eight important directors would be given their own budgets and camera crews and dispatched to Munich to record their personal visions of the 1972 Olympics. What nobody could have anticipated, perhaps, is how similar many of those visions would be. Too often during “Visions of Eight” the Olympic events are reduced to slow-motion ballets that finally just repeat themselves.

There is, I suppose, some interest in Kon Ichikawa’s slow-motion replay of the 100-meter dash; the world’s fastest men are slowed down to grotesque life-sized robots with pumping cheeks and contorted faces, and we get a feeling for the event’s special agony. But the sequence is held too long; and so is Arthur Penn’s segment on pole vaulting. We get jump after jump in slow motion, but all of that footage doesn’t tell us as much about the vaulters as one single shot, near the end, where Penn shows us a competitor meticulously removing an invisible piece of lint from his hand grip.

There are other small touches that make the film worth seeing. In Claude Lelouch’s segment on the losers, for example, there’s an astonishing display of bad sportsmanship from a defeated boxer who refuses to leave the ring. For three or four minutes caught in a single take, he expresses his contempt for the decision and his outrage at the crowd (which generously boos him).

There’s another kind of losing, too. In Mai Zetterling’s segment, we see a massive weightlifter as he nervously circles the weights, and we can almost taste his apprehension. We’ve seen other competitors lift this bar (which takes five men to carry from the stage), and we know how heavy it is. So does he. He circles the stage, breathing deeply, trying to psych himself into the lift. He approaches the bar, grabs it, backs away. Circles some more. Just looking at him, we sense he can’t lift it. He approaches the bar again, heaves, gets it a foot off the ground, then throws it back down again with disgust and walks off the stage. In a moment like that, we begin to understand something of the difficulties of the weightlifter.

The movie’s still, beautiful center is occupied by the fawnlike Soviet gymnast Ludmilla Tourischeva. She’s in Michael Pfleghar’s segment on the women in the Olympics, and he shows us her entire routine on the uneven parallel bars. It is an exercise of grace made possible through superb athletic skill, and he wisely refuses to gimmick it up with cuts or slow motion. (Surely, as a general rule, the beauty of the Olympic events is that they take place in real time; slowing down Tourischeva’s gymnastics would have missed the point.)

The most successful segment was directed by John Schlesinger, who considers the twenty-six-mile marathon race from the point of view of one of the British competitors. We see the runner in his home in the north of England, getting up every morning to run ten miles to and from work. Some days he runs home for lunch. On Saturdays he does a complete marathon course. We get a real feel for the loneliness of the long-distance runner as we see him running on dreary country roads during an overcast morning.

Then Schlesinger shows the runner at the Olympics, and in a stunning use of imagination, he gives us dream-like sequences designed to suggest what goes through the mind of the marathon runner: Memories of the long morning runs, thoughts of his family, wordless awareness of his surroundings. Schlesinger intercuts this footage with rather superficial coverage of the murdered Israelis. His is the only segment to refer to the tragedy, and at first he doesn’t really seem to have anything coherent to say. But then he pulls his images together in his last few minutes; as Avery Brundage is making his closing speech as if the whole Olympic pageantry hadn’t already turned to ashes with the murders, a final dogged marathon runner, hours behind the rest, stubbornly runs into the stadium and crosses the finish line. That’s it, Schlesinger seems to be saying: The dignity of this loser, still loyal to his sport, eclipses the electric scoreboards and the official blazers.