The body language says everything. The two men walk ahead, carrying gear, engaged in conversation. She walks behind them, alone, carrying her own gear and oxygen tank. They don’t lend her a hand, or offer to carry the tank for her, and what this says is that, at 91, they do not think she needs special consideration. She’s one of the guys.

If Riefenstahl were anyone else, this footage alone would justify a documentary. The images of her exploring the ocean bottom are extraordinary, holding out the promise that old age can be held indefinitely at bay. But Riefenstahl has not, of course, lived a normal life, and the actions which will forever define her reputation took place not in her 60s but in her 30s, when she directed two documentaries that will always be linked with Adolf Hitler and his Nazi party.

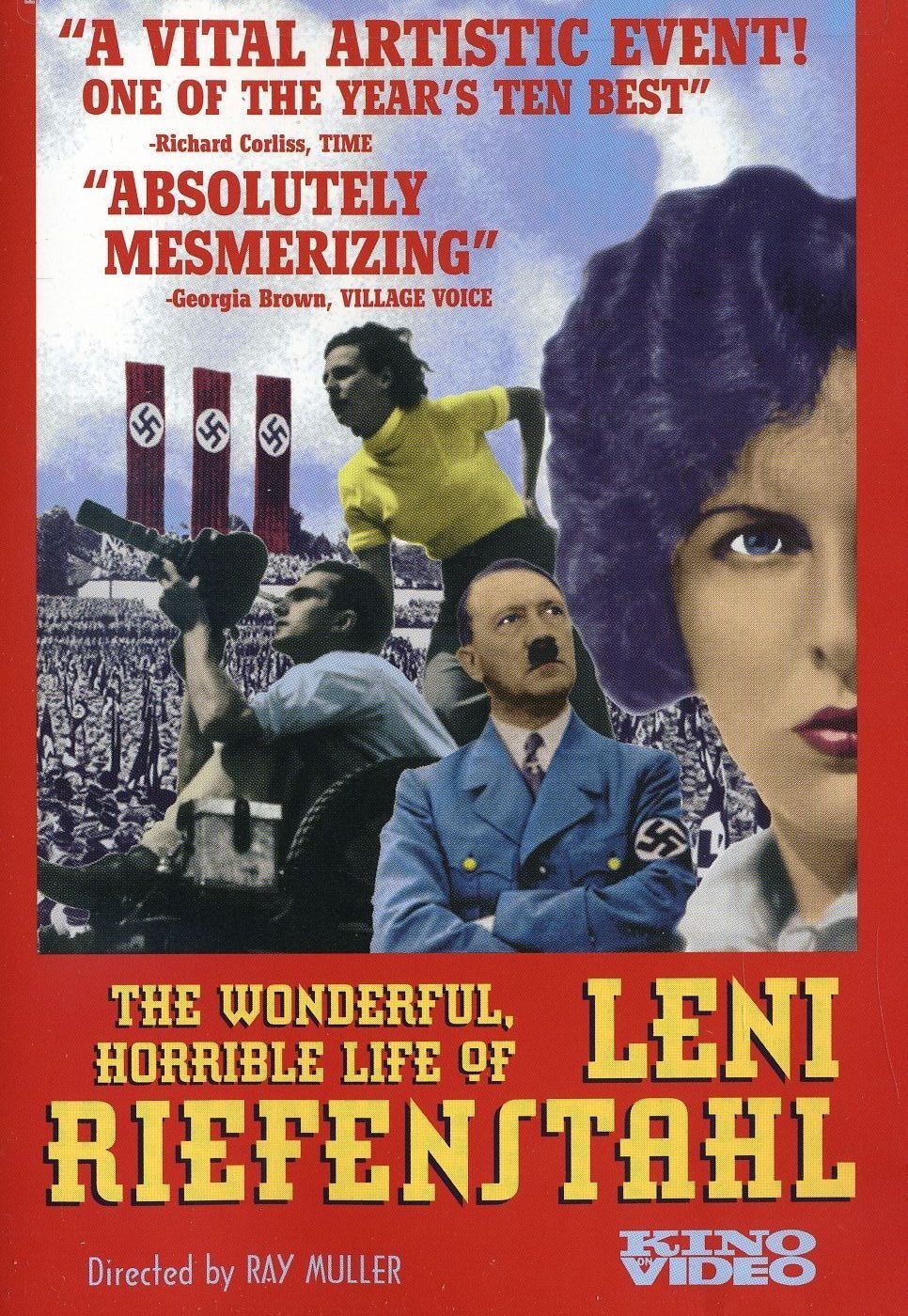

“Triumph of the Will” (1934) was a film about the Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg, an event largely staged for the benefit of her camera, which showed a confident Hitler nodding approvingly as massed ranks of Nazi troops march in review. Three years later, she directed “Olympia,” a documentary on the Berlin Olympiad.

These are by general consent two of the best documentaries ever made. But because they reflect the ideology of a monstrous movement, they pose a classic question of the contest between art and morality: Is there such a thing as pure art, or does all art make a political statement? This documentary by Ray Muller was made with Riefenstahl’s agreement, if not always with her happy cooperation. He reconstructs her career, beginning with her emergence as a star and director of German “mountain films,” a late-1920s genre that glorified a cult of idealized heroism with stories of adventures in the German Alps.

Hitler saw her mountain films and apparently became a fan (there were persistent rumors, but never any evidence, that he became her lover).

He hired her to make a short film about the 1933 Nazi rally, and then her great documentary about the Nuremberg event.

Riefenstahl is at pains to insist she was never a member of the Nazi Party. Her position has always been that she was an artist, working in a vacuum. The tragedy of her career, from her view, is that “Triumph of the Will” and “Olympia” gained such fame, and were so closely identified with Nazism, that she was never able to finish another film. There were other documentaries about the Nazi rallies, but nobody remembers the others; only hers, because it was so good.

“The Wonderful Horrible Life of Leni Riefenstahl” is not convinced by her lifelong self-justification, and subjects her to strenuous on-camera questioning. She is unyielding. More than able at the age of 91 to defend herself, she has rehearsed over the years an elaborate explanation and justification for her behavior. There is no mention in her films of anti-Semitism, she points out. She did not know until after the war about Hitler’s genocidal policies against the Jews. She was a naive artist, unsophisticated about politics, detached from Nazi party officials with the exception of Hitler, her friend – but not a close friend. She was concerned only with images, not ideas.

And so on. But it has been pointed out that the very absence of anti-Semitism in “Triumph of the Will” looks like a calculation; excluding the central motif of almost all of Hitler’s public speeches must have been a deliberate decision to make the film more efficient as propaganda. Nor could it have been easy for a film professional working in Berlin to remain unaware of the disappearance of all of the Jews in the movie industry.

In the film, Riefenstahl engages in onscreen debates with Muller, and then is seen visiting the site of the 1938 Olympiad with the surviving members of her film crew. They talk about some of their famous shots – from aerial techniques to the idea of digging a hole for the camera, so that athletes could loom over the audience. Shots from the film are a reminder of how beautiful and effective it was.

And we sense Riefenstahl’s true passion for filmmaking. But there are candid moments, when she is not aware of the camera, when she shares quiet little asides with her old comrades, which, while not damning, subtly suggest a dimension she is not willing to have seen.

The impression remains, after the film is over, that if Hitler had won, Leni Riefenstahl would not have been so quick to distance herself from him. Her postwar moral defense is based on technicalities. Undoubtedly in the atmosphere of the Nuremberg Trial she was not eager to face conviction or punishment as a war criminal.

But, ironically, if she had confessed and renounced her youthful ideas, she might have had a more active career. It is her unconvincing, elusive self-defense that continues to damn her.

This movie is fascinating in so many different ways: As the story of an extraordinary life, as the reconstruction of the career of one of the greatest of film artists, as the record of an ideological debate, as a portrait of an amazing old woman. At its heart is the question of the soul and purpose of art. Can art be detached from its context? The pyramids were constructed at the cost of the lives of uncounted thousands of slaves. Do we remember them today? Do their deaths diminish the monuments they built? One dilemma of Leni Riefenstahl’s wonderful, horrible life is that it has been so long. It would be so much easier to simply study the films without still having to deal with the unrepentant woman.