The Weathermen orchestrated a string of bombings, called for the “Days of Rage” in Chicago, were in a vanguard of a more widespread anti-war movement that saw National Guard troops on the campuses, the Pentagon under siege by protesters including hippies who vowed to levitate it, and the infamous Chicago 7 trial. Whether the protest movement hastened the end of the Vietnam War is hard to say, but it is likely that Lyndon Johnson’s decision not to run for re-election was influenced by the climate it helped to create.

One crucial moment documented in this film is when SDS, with 100,000 members an important force among American young people, was essentially hijacked at its 1969 national convention in Chicago by the more radical Weather faction.

“Institutional piracy,” Todd Gitlin called it; one of the founders of SDS and later the author of a landmark book about the student left, he watched in dismay as the Weather faction advocated the violent overthrow of the U.S. government. Their program of terrorist bombings, he said, “was essentially mass murder.” When a innocent person was killed in one of its early bombings, the group however decided that was “a terrible error,” and took care that nobody was injured in a long series of later bombings, including one at the Capitol in Washington, D.C. But a Greenwich Village townhouse used by the Weathermen as a bomb factory was destroyed in an accidental explosion that killed three bombmakers.

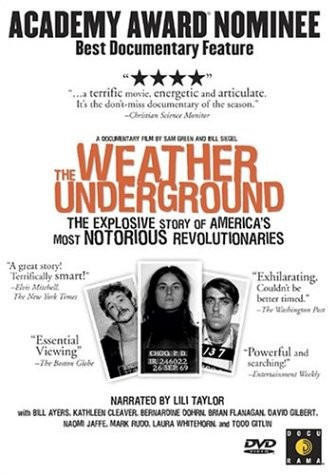

The Weathermen tactics were “Custeristic,” Black Panther leader Fred Hampton sardonically observed at the time. When the Weathermen called for Days of Rage in Chicago in 1969, he said they were “taking people into a situation where they can be massacred.” He was right, but he was himself soon massacred, in a still-controversial shooting that Chicago law enforcement officials described as a shoot-out but which physical evidence indicated was an assassination. (After the Tribune cited “bullet holes” proving Hampton had fired back, a Sun-Times team ran photographs revealing the holes to be nailheads.) The documentarians, Sam Green and Bill Siegel, are too young to remember this period personally–and, indeed, many viewers of the film may discover for the first time how ferociously the war at home was fought. The film interviews surviving players in the drama, including Bernadette Dohrn, her husband Bill Ayers, Naomi Jaffe, Mark Rudd, David Gilbert, Brian Flanagan and Gitlin. Dohrn, today the head of a program for juvenile justice at Northwestern University, still burns with the fire of her early idealism, as do Ayers and Jaffe, and you can hear in the voice of Gilbert (serving a life sentence for his involvement in a fatal robbery of a Brinks truck), the pain he felt because his country was committing what he considered murder in Vietnam.

Ironically, many charges against the Weathermen had to be dropped because the FBI had violated the law with its “Cointelpro,” a secret agency to discredit the left. After the war ended and the Weatherman movement faded away, Dohrn and Ayers lived in hiding for several years with their children–an existence some say inspired the 1988 movie “Running on Empty.” Eventually they turned themselves in, and today are leading productive, unrepentant lives.

I see Dohrn at the Conference on World Affairs at the University of Colorado, where she is as angry about the unnecessary criminalization of poor (often non-white) American young people as she was then about the war. She has, you must observe, the courage of her convictions.